Theology Central

Theology Central exists as a place of conversation and information for faculty and friends of Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Posts include seminary news, information, and opinion pieces about ministry, theology, and scholarship.

It’s Time To Live It

Among the books that I was reading last week was Peter Sammons’s volume on Reprobation and God’s Sovereignty. Perhaps I should say that if reprobation is understood as symmetrical with election—i.e., that God elects and then creates some individuals simply to condemn them forever—then I do not judge it to be true. Nevertheless, I found benefit in reading Sammons. One particularly challenging point is that we cannot accept the benefits of Providence when it brings obvious blessing into our lives while complaining about our circumstances when things seem to go wrong (Job 2:10). Directly or indirectly, even the evil that happens in the world is ordained by God for good ends. If we really believe Romans 8:28, then we must see God’s hand in the worst of calamities.

The week I spent reading the book was rather arduous in other ways. It was finals week at the seminary, a time for grading papers, administering exams, closing out courses, preparing for board meetings, and of course observing commencement. The week was made more difficult than usual because our administration had to lop a day out of the schedule (no fault of theirs). Instead of graduating our students on Saturday morning as we always have, we graduated them on Friday night.

Further complications came from the pastoral side of my life. Our deacons had to meet after church on Wednesday night to address a family emergency. Another member of our fellowship had a mother who was dying, and she passed away on Friday morning. Combined with the seminary’s schedule, these and other factors resulted in a pressured week of late nights, early mornings, and little sleep. I was looking forward to resting on Saturday.

Both Debbie and I had responsibilities after the commencement ceremony. She was responsible to check in the rented and borrowed caps, hoods, and gowns. Consequently, we didn’t pull in the driveway until around 10:00 PM. Given the tension of the week, I lay awake for a long time on Friday night.

Saturday had the potential to be a much more relaxed day, though the situations from church were still pressing. Debbie was preparing a late breakfast at around 8:00 when she glanced out the window at the driveway. “Where’s the car?” she asked.

I looked out the window then, and sure enough, there was no car. I hadn’t even dressed for the day, but I pulled on jeans and a tee-shirt and walked out to investigate. Where the car had been parked was a pile of shattered glass. The obvious conclusion was that our car had been stolen. I was a bit surprised because I put a locking bar on the steering wheel. Nevertheless, there was the driveway, empty except for the heap of broken glass.

The obvious first step was to call the police. Ten minutes later an officer arrived. He took our information and viewed the pile of glass. He told us that earlier in the morning a stolen car had been recovered in front of our house, where it had been abandoned by thieves. The thieves had apparently just changed cars. “Probably juveniles,” he said, “Ages ten to fourteen. That’s typical. You can hope that they’ll joyride with your car and abandon it where it will be found.” He also told us about occasions when he had arrested the same juveniles three times in stolen cars. They were always put back on the street. “It’s not the police,” he said. “We try to enforce the law. It’s the county that won’t prosecute.”

Well.

After the officer left, I took up the matter with my insurance company. On Saturday morning their regular offices weren’t open, but I was able to call a weekend number to file a claim. The person I spoke with was as helpful as she might have been, but at that stage there was little that she could do except to write up the report.

Next came a quick call to the seminary’s business manager. Fourth Baptist owns a car that it lends out for ministry purposes, and I asked whether I might use it. Instead, the business manager offered to lend me his wife’s car. It helps, I suppose, that the business manager is married to one of my sisters.

Debbie and I still had to travel to the town where I pastor. It was now well past noon, and we hadn’t eaten lunch yet. We stopped to grab something along the way, and we finally reached our ministry home late in the afternoon. We completed several necessary chores, ate a quick supper, and then drove another fifteen miles to visit our bereaved church member.

That may have been the most encouraging part of the day. What we heard from our friend was his complete acceptance of God’s workings in his life. He blessed his mother’s memory. He told us about moments he had relished with her during her final week. He expressed his hope that God would use the situation to reach unsaved members of his family. We had gone to offer him comfort and encouragement, but we received far more than we gave.

That night the police called to tell me that my car had been recovered. The window had been shattered (we knew that). The steering column was torn up. The car had been ransacked and the inside was badly messed around. And it was being taken to an impound lot.

Never had I guessed the Byzantine machinations and labyrinthine procedures that would be necessary to recover a car from impound. These entailed multiple phone calls and multiple stops. Once I had cleared those hurdles, the car was released. Since it is undrivable, however, it will have to be towed to a shop. All those matters are now in the hands of the insurers.

Most people would consider this week to be a bad one, and there is no use denying that the circumstance is a minor calamity. Naturally, Debbie and I comfort ourselves by telling each other how much worse it might have been, and that is a real consideration. We will suffer a financial loss (insurance doesn’t cover everything), but our home is intact and we were not harmed in our persons.

The greatest comfort, however, is this. These calamitous circumstances were ordained by an all-wise and loving God. They were ordained for His glory. They were ordained for our good. God knows what He is doing, even if we do not. He still deserves our adoration, our praise, and particularly our gratitude. God could have protected us from the evil, but He chose not to. We can only trust Him, that what He is doing will be better, and that it will produce greater glory and greater good. So we humble ourselves before Him and accept His dispensation as if He were visibly before us directing events. We have thanked Him in the past when events seemed good to us. Now it is time to thank Him when events seem bad. To Him alone be glory.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Commit Thou All Thy Griefs

Paul Gerhardt (1607–1676); tr. John Wesley (1703–1791)

Commit thou all thy griefs

And ways into His hands,

To His sure trust and tender care,

Who earth and heav’n commands;

Who points the clouds their course,

Whom winds and seas obey,

He shall direct thy wand’ring feet,

He shall prepare thy way.

Thou on the Lord rely,

So safe shalt thou go on;

Fix on His work thy stedfast eye,

So shall thy work be done:

No profit canst thou gain

By self-consuming care,

To Him commend thy cause, His ear

Attends the softest pray’r.

Thine everlasting truth,

Father, thy ceaseless love,

Sees all thy children’s wants, and knows

What best for each will prove;

And whatse’er Thou will’st

Thou dost, O King of kings;

What Thine unerring wisdom chose,

Thy pow’r to being brings.

Thou ev’ry where hast sway,

And all things serve Thy might,

Thy ev’ry act pure blessing is,

Thy path unsully’d light:

When Thou arisest, Lord,

What shall Thy work withstand?

When all Thy children want, thou giv’st,

Who, who shall stay Thine hand?

A Complex Event

Sometimes the events of biblical prophecy are relatively simple. The foretold event occurs and the prophecy is fulfilled. From that moment, it slips into the past. Noah prophesies the flood, and it comes. Elijah prophesies a drought, and the rain stops. Micaiah prophesies the death of Ahab, and Ahab is killed. Even where the event takes time, it is a single, simple event.

Other times, the events of biblical prophecy are complex. In this case, complex does not necessarily mean complicated, but rather consisting of multiple parts. The most clearly complex event in biblical prophecy is the coming of the Messiah.

Arguably, the first messianic prophecy is about the seed of the woman who will bruise the serpent’s head (Gen 3:15). Jacob prophesied the coming of “Shiloh” of the line of Judah, from whom the scepter would not depart (Gen 49:10). Balaam foresaw a star coming out of Jacob and a scepter out of Israel, one whom he calls, “He that shall have dominion.”

To these earlier foretellings, the later prophets added much detail. The coming Messiah would be a prophet like Moses (Deut 18:15). He would be a king of David’s line (2 Sam 7:11–16). He would be a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek (Ps 110:1, 4). He would rule the nations with a rod of iron (Ps 2:8–9). He would give His life for the iniquities of His people (Isa 53). Dozens more prophecies foretold the events of Messiah’s birth, life, activities, death, and, according to 1 Corinthians 15:4, even His resurrection.

A new wrinkle was pressed into the messianic timeline by Daniel’s prophecy of the seventy weeks (Dan 9:24–27). With this prophecy it became possible to know the exact year of Messiah’s arrival hundreds of years in advance. What Daniel prophesied, however, was not Messiah’s birth, but most likely His triumphal entry.

This wrinkle leads to the question of what exactly is meant by Messiah’s coming. When should students of the Bible reckon that Messiah has come? At His birth? His baptism? His triumphal entry? Some other event?

In a certain sense, any of several events could be pointed to as the coming of Messiah. Indeed, in the fullest sense, Messiah has not come yet, for He is not yet exercising the fulness of royal sovereignty over the earth through Israel. Perhaps this factor is what Jesus’ disciples had in mind when they asked, “What shall be the sign of thy coming?” (Matt 24:3). Even though Messiah was right in front of them and was even talking with them, He had not yet come in the fulness of His power.

Jesus answers their question in a way that discloses even more about His coming. He refers to it in the future tense. He claims that it will occur only after a series of increasingly severe judgments. When it happens, it will be as unmistakable as the lightning flashing across the sky (Matt 24:27). It will culminate with the sign of the Son of Man in heaven (Matt 24:30). The grammar in that last statement probably includes a genitive of apposition: when the Son of Man appears in the heavens, He will be the sign.

By the end of the Gospels, it is clear that Jesus is going to leave earth and that He will return someday (John 14:1–3). At the beginning of Acts He bodily ascends into heaven (Acts 1:9–10), leaving many messianic prophecies to be fulfilled at His return. In other words, what the Old Testament speaks of as an event (the coming of Messiah) turns out to be a series of events and even a series of comings. Christians now speak without hesitation of Jesus’ first coming, which is past, and His second coming, which is still future. What the Old Testament speaks about as a single thing—the coming of the Messiah—is thus a complex event.

What is true of Jesus’ coming in general is also true of His second coming in particular. The second coming is also a complex event. The prophecies that remain to be fulfilled do not all take place at once. Some are fulfilled when He arrives on earth. Others are fulfilled when He establishes His millennial kingdom. Others will not be fulfilled until the end of the Millennium.

Dispensationalists insist that the coming of Jesus will occur in at least two stages. First, He will come in the air to rapture His Church. These Church saints will then live with Him for seven years in heaven, at which point they will accompany Him when He returns to earth to judge His enemies and establish His millennial kingdom. The coming in the air and the coming to earth are not really two separate comings, but two stages of the same second coming, which is a complex event.

That is why dispensationalists learn to be careful in the way they speak about the second coming. When they talk about this event, they may mean Jesus’ coming in the air at the Rapture or they may mean Jesus’ descent to earth to establish His kingdom. Sometimes they may mean both at once, preserving the complex nature of the event. Often, however, they find it necessary to specify which stage of the second coming they are talking about.

Anti-dispensationalists sometimes find this way of speaking humorous. They may jibe, “Do you mean the first second coming or the second second coming?” Viewing Jesus’ coming as a complex event, however, means that there is nothing implausible in the idea that the second coming occurs in stages. In fact, dispensationalists affirm that the Bible rather clearly shows these multiple stages. The second coming must be viewed as a complex event.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Bless, O My Soul, the Living God

Isaac Watts (1674–1748)

Bless, O my soul, the living God;

Call home thy thoughts that rove abroad,

Let all the pow’rs within me join

In work and worship so divine.

Bless, O my soul, the God of grace;

His favors claim thy highest praise;

Why should ungrateful silence hide

The blessings which his hands provide?

‘Tis he, my soul, that sent his Son

To die for crimes which thou hast done;

He owns the ransom, and forgives

The hourly follies of our lives.

The vices of the mind he heals,

And cures the pains that nature feels—

Redeems the soul from hell, and saves

Our wasting life from threat’ning graves.

Our youth decay’d his pow’r repairs;

His mercy crowns our growing years;

He fills our store with ev’ry good,

And feeds our souls with heav’nly food.

He sees th’ oppressor and th’ opprest,

And often gives the suff’rer rest;

But will his justice more display

In the last great rewarding day.

Episode 52 – The Word and the Testimony – The Central Hymn with Roy Beacham & Jon Pratt

In this episode, Dr. Roy Beacham & Dr. Jon Pratt discuss the history and significance of the Central Hymn. “The Word and the Testimony,” based on Isaiah 8:20, has served as the motto of Central Seminary and emphasizes the centrality of the Word of God.

Keywords

Central Seminary, Central Hymn, history, significance, motto, Word and testimony, Isaiah 8:20, professors, anecdotes, memories, Christological, evangelistic, ministry

Takeaways

- The Central Hymn is based on Isaiah 8:20 and has served as the motto of Central Seminary in emphasizing the importance of the Word and testimony.

- The hymn reflects the legacy and mission of Central Seminary to train leaders who are committed to the Word and its centrality in preaching and teaching.

Quotes

- Jon Pratt: “Little did I know that the song that I was listening to as a kid would be the main theme song of the seminary where I would be teaching at one day.”

- Roy Beacham: “Return to the word, follow the word, follow the Lord. If not, your future is dim, there’s no light.”

The Word and the Testimony

by Dr. Richard V. Clearwaters

Founder of Central Seminary

Isaiah 8:20

To the Law and Testimony

Ever shall be Central’s song;

For within these sacred pages

We have found the Father’s Son.

Of our service He is worthy,

For His form we plainly see,

In the pages of the Volume

Daily witnessed there for me.

Words there great and oh so precious,

Ever speaking loud and clear

To lost sinners, poor and needy,

By God’s nature, now drawn near.

For the hunger that He gives us,

By this Self of His within;

We are pure in daily living,

Through the power He gives to men.

In the world and no part of it,

We will shun its sin and lust;

For the Savior’s image charms us

Through the Book, for us to trust.

In the highways and the byways,

In the halls with noise and din;

Here at “Central” He is central,

Like the Book that brings us Him.

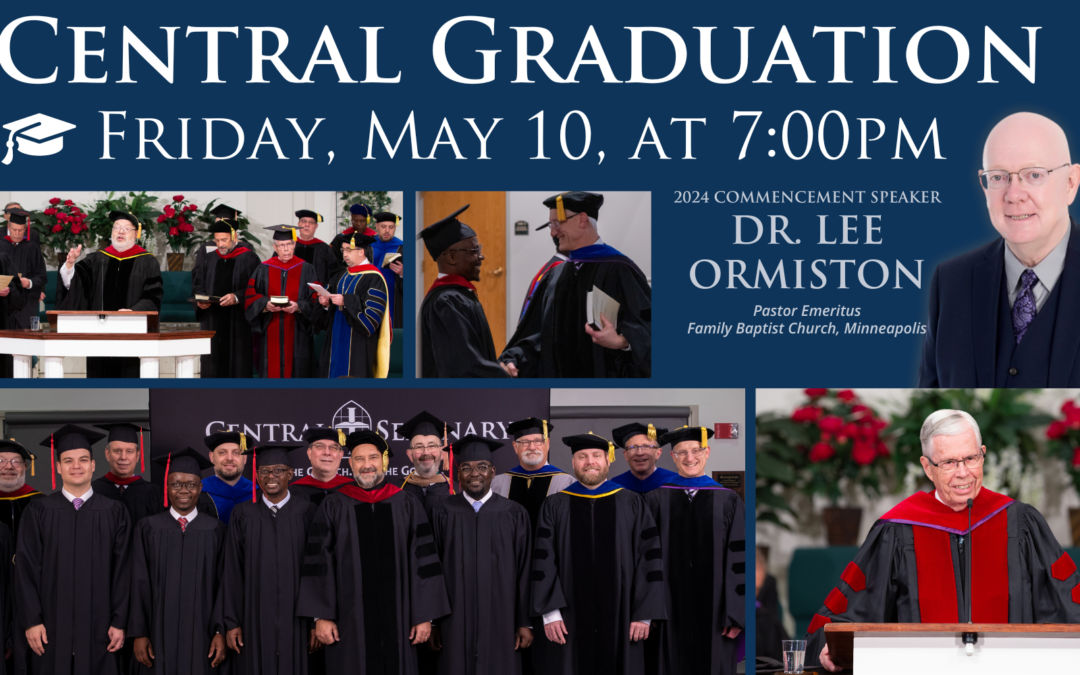

Ending Another School Year

Here at Central Seminary the school year draws to an end in May. It is a bittersweet time. The “bitter” side of bittersweet comes from two sources. One is because the season always involves intense work. Professors are always crunched to do final grading. We don’t get much else done for a couple of weeks. The registrar and office help must scurry in preparation for graduation activities, which include the semi-annual board meeting, graduation practice, a meal for graduating seniors and their families, and of course the commencement ceremony. During these weeks we tend to run on adrenaline.

The other part of the “bitter” in bittersweet comes from the departure of our graduates. Over the years we see them in class repeatedly. We develop relationships with them outside of class. We become friends, and our lives begin to revolve around each other’s. With graduation, however, the relationship changes. While the friendships don’t dissolve, they tend to become more distant for the simple reason that we don’t see each other as regularly.

But of course, that change leads directly into the “sweet” side of the bittersweet season. Students graduate because they have finished their preparation. They no longer need to be in class. Instead, they can devote themselves to the work that the Lord gives them. They are able to minister effectively on their own, and that is exactly why we invest in them to begin with.

One of the blessings of teaching is that you get to see your students go on to put their learning to use. I’m now in my 27th year of teaching at Central Seminary, and I am delighted to have former students who are ministering effectively around the United States and even around the world. It is a special pleasure to have seen numbers of them surpass me in various ways (for example, I work for two of my former students). Many of them are doing work that I never could, and that is cause for rejoicing.

For years our graduation regimen has stayed the same, but this Spring it is changing in multiple ways. In the past, the activities of graduation week were spread over three days, from Thursday when the board committees met until the Saturday commencement ceremony. This year, however, we are trying to fit it all into one day. Friday will begin with board meetings until about noon. After a brief lunch the board will continue to meet while students attend the graduation practice. The graduation meal, which used to be a breakfast on Friday morning, will now become a dinner on Friday afternoon. The ceremony itself will be held on Friday evening.

The schedule is not the only change. Over the past several years we have shifted toward Zoom technology as the platform for delivering education. We are now at the point where few of our students are local. Many live in distant countries. For the first time, one of our graduates has been unable to get a visa to attend commencement. Due to these changes, Central Seminary will shift its commencement to include a significant livestream component.

We also have an unusually small graduating class this year. Partly that is because we went through a slump in recruiting several years ago (that has been corrected and we have a robust student population now). Partly it is because students are taking longer to complete their programs. Mostly, we don’t know why the numbers have worked out as they have. At any rate, this is a good year to experiment with a new format for graduation.

Today I signed the final drafts of a major project for a Doctor of Ministry graduate. This week I will teach the final classes before Final Exam Week. Next week we will administer those exams, and the professors will have an accelerated schedule to submit grades for graduating students. Then on Friday, May 10, the school year will conclude. I anticipate waking up a week from Saturday to the first day of summer break.

The expression “summer break” hardly seems an adequate designation anymore. Although the graduates will have departed, we will nevertheless be offering courses through much of the summer. Those months will also involve a fair amount of travel as administrators and faculty represent the seminary at the annual meetings of various fellowships. In July most of our professors will travel to the Bible Faculty Summit to interact with peers from sister institutions. By August, each of us will be gearing up to face the faculty in-service meetings, which will conclude just before the next academic year begins. These days, teaching at Central Seminary keeps us busy all twelve months of the year.

Nevertheless, graduation represents a milestone, and not only for those who are graduating. Each commencement is a rite of passage, as much for teachers and administrators as for students. It marks an academic year coming to a close, a task accomplished once for all, and a new circle of students advancing into the next stage of their service for the Lord.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Christ’s Care of Ministers and Churches

Philip Doddridge (1702–1751)

We bless th’ eternal Source of light,

Who makes the stars to shine;

And, through this dark beclouded world,

Diffuseth rays divine.

We bless the churches’ sovereign King,

Whose golden lamps we are;

Fixed in the temples of His love

To shine with radiance fair.

Still be our purity be preserved;

Still fed with oil the flame;

And in deep characters inscribed

Our heavenly Master’s name.

Then, while between our ranks He walks

And all our state surveys,

His smiles shall with new luster deck

The people of His praise.

Equality

We often hear equality spoken of as if it were one of the greater goods. The assumption seems to be that any form of inequality is intrinsically unjust, and that inequalities only exist because one person or group of people is oppressing another. Inequalities that convey advantages are now called privilege, and privilege is regularly and roundly denounced. Justice (it is thought) requires the abolishment of privilege.

Perhaps it is worth asking what real equality would look like. For example, what would complete political equality involve? A truly egalitarian political system would be one in which offices were lifted out of the realm of favoritism. To do that, they would have to be filled by rota. Everyone would serve once in every office. Of course, to do that, terms of office would have to be shortened dramatically. Suppose we tried to give every citizen the chance to serve as President of the United States for exactly one hour. In that system, we would have approximately 8,766 presidents over the course of a single year.

While that number seems high, it would still not give everyone the opportunity to be president. For every resident of the United States to serve a single one-hour term would take just over 34,223 years, which is almost as long as we have to stand in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles. So what is the alternative? If everyone cannot serve, should we perhaps draw lots for each hour of office?

We could combine the methods of rota and lot, particularly if we take into account all of the public offices that exist in the United States. Besides the president and vice-president, we have about 500 people in Congress, fifty governors and lieutenant governors, around 7,000 state legislators, an army of local officials, plus the entire judiciary (in a truly egalitarian system, everybody would have a turn at being a judge). The total comes up to something like half-a-million offices.

Suppose each office were filled by a different person each day, and that each officeholder was chosen by lot. In this scheme, every American would serve in some office about one day every two years. The particular office—whether federal, state, or local—would be entirely up to chance. This system might give us our best shot at genuine equality. It would also have other advantages, such as the complete elimination of election campaigns. Furthermore, the amount of damage that any one officeholder could do would be limited.

On the other hand, that kind of equality would create chaos. A significant number of officeholders would have little interest in serving their day. They would view a day in office as an unwelcome interruption, just as many now perceive a day of jury duty. Another number would see a day in office as little more than an excuse to party. Of those who really wanted to serve, only a fraction would bring the necessary skills and qualifications. Who really needs that kind of equality?

Political equality does not and cannot exist. In my community lives a woman named Ilhan Omar. She and I do not have an equal voice in the political process. She gets to act directly upon federal legislation, and I do not. Her level of power and privilege far exceeds, and in fact contradicts, mine. She rarely or never represents my interests, opinions, views, and perspectives.

How did she get to be so privileged? It happened through favoritism. She was elected to office by people who live near us both. The largest bloc of people who chose her share the religion and ethnicity into which she and they were born. In other words, her privilege is based in unearned features. She sometimes talks about equality, but I have never heard her advocate the kind of equality that would give me the same voice in Washington that she has.

The American founders were not ignorant of the difficulty in creating complete equality. When they declared that “all men are created equal,” they immediately qualified their statement with an appositional clause implying that all people are equally “endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights.” They never dreamed of creating a system of full political equality, partly because they knew that crude population was not the only interest that needed to be represented in a just system of government. Nevertheless, they did understand that under a just government people must stand as equals before the law. (I note in passing that this principle is violated every time Congress exempts itself from laws that it passes to govern the rest of the nation.)

These same founders also recognized that people must all equally answer to God. Answering to God is a far more serious matter than answering to civil authority. Consequently, the founders inferred that governments have no right to mandate how people must relate to God. Instead, just governments must refuse to establish religions and must also protect the free exercise of religion (as long as those exercises do not transgress in matters that governments do have a right to legislate). So long as we have not entered the Kingdom of God, civil authorities have no right to mandate the worship of the true and living God or to forbid the worship of false gods.

The point is that equality is not the greatest good. It is not always a good at all, particularly when understood as equality of condition. Political philosophies or movements that constantly appeal to equality should rouse our suspicions. At the end of the day, almost all egalitarians are faux-egalitarians. What they want is not true equality, but a way to promote privilege for their own crowd.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Psalm 37

Isaac Watts (1674-1748)

Why should I vex my soul, and fret

To see the wicked rise?

Or envy sinners waxing great,

By violence and lies?

As flow’ry grass cut down at noon,

Before the ev’ning fades,

So shall their glories vanish soon,

In everlasting shades.

Then let me make the Lord my trust,

And practice all that’s good;

So shall I dwell among the just,

And he’ll provide me food.

I to my God my ways commit,

And cheerful wait his will;

Thy hand which guides my doubtful feet,

Shall my desires fulfil.

Mine innocence shalt thou display,

And make thy judgments known,

Fair as the light of dawning day,

And glorious as the noon.

The meek at last the earth possess,

And are the heirs of heav’n;

True riches, with abundant peace,

To humble souls are giv’n.

Rest in the Lord, and keep his way,

Nor let your anger rise,

Though Providence should long delay,

To punish haughty vice.

Let sinners join to break your peace,

And plot, and rage, and foam;

The Lord derides them, for he sees

Their day of vengeance come.

They have drawn out the threat’ning sword,

Have bent the murd’rous bow,

To slay the men that fear the Lord,

And bring the righteous low.

My God shall break their bows, and burn

Their persecuting darts,

Shall their own swords against them turn,

And pierce their stubborn hearts.

Vocation and Vocations

[This essay was originally published on February 5, 2016.]

The Reformers erected the doctrine of calling in reaction to the Romanist distinction between clergy and laity. At the time, Catholics recognized only two vocations: the calling to consecration (which typically involved joining an order) and the calling to ordination (priesthood). In other words, monks and priests had a vocation; other people did not.

Over against this distinction the Reformers insisted that God calls all Christians. Their vocation is whatever station enables believers to demonstrate God’s love by serving others. In the Protestant view of vocation, ministers are called—but so are bakers, farmers, shopkeepers, and tradesmen.

The Protestant view of vocation grows out of 1 Corinthians 7:17-22. In this passage, vocation refers primarily to God’s calling of the individual to salvation. That is the first and highest calling for any Christian—to be a child of God, placing His character on display in the world, working out our salvation. Paul’s point in this passage and its surrounding context is that every lawful station of life (marriage, singleness, slavery, freedom, circumcision, uncircumcision) provides the opportunity to do just that. We are to use whatever station in which we find ourselves for God’s glory. The Reformers’ doctrine of vocation—the Protestant doctrine of vocation—is really the Pauline and biblical doctrine of vocation.

This Pauline doctrine of vocation is probably what lies behind Paul’s cryptic comment in 1 Timothy 2:15. He says that the woman will be saved in childbearing if she continues in faith, love, holiness, and self-restraint. Paul certainly does not mean to teach that giving birth somehow forgives a woman’s sins and secures eternal life. Given the context, he is most likely saying that maternity is a station that allows a woman to demonstrate how God’s saving grace is working in her life. A minister exhibits his salvation through his preaching and teaching, but Paul forbade women to teach or usurp authority over men. Are they then relegated to the position of second-class Christians? Not at all! Maternity (and domesticity) enable the stay-at-home mom to place her salvation fully on display.

This is an important truth. Pastors have the privilege of spending hours each day in the Scriptures so that they might minister the Word of God. Stay-at-home moms may struggle to find a quarter of an hour for devotions. Some might think that the pastor occupies the more spiritual position, but that is not what Paul says. A woman who rightly fulfills her station as a mother is bringing glory to God, just as the minister is.

What is true of the stay-at-home mom is true of all lawful vocations. They are ways of showing God’s love by serving others. They are ways of working out our salvation. Every vocation provides a giant screen upon which the Christian can project the manifold grace of God.

The difference is that the pastor’s vocation takes him into the study, away from the rush and tumble of life, to listen quietly to God. The mother’s vocation takes her into playrooms and grocery stores, and she does things like changing diapers, preparing meals, and wiping runny noses. To use the traditional labels, the minister’s life is contemplative while the mother’s life is active.

The point is that both of these lives are callings. Both are spiritual. Both bring glory to God if they are conscientiously pursued.

Most Christians actually occupy multiple callings. One of those callings pertains to all believers: the calling to place salvation on display. Other callings are discovered in our particular situations. A married man is called to love his wife. A father is called to bring up his children in the nurture and admonition of the Lord. Whatever we do to gain a living is also our calling, whether it involves balancing books, performing surgeries, or flipping burgers. Obviously some callings may change over time. A wedding marks the end of singleness (one calling) and the beginning of marriage (a different calling). A transition between jobs also usually marks a change in callings.

Some callings we choose; some are chosen for us. A slave does not typically choose slavery, though Paul says that if slaves are given a choice, they should choose freedom. Nevertheless, both slavery and freedom are callings. Sometimes our choice of callings is restricted by circumstances: there are no accountant jobs open, so we sweep floors instead. When such situations occur, we must not feel ourselves to be victims or become bitter against the calling into which God has led us. We must use it for His glory.

Other times God allows us to select from multiple options. How then should we choose? Too many Christians assume that the most financially rewarding option must be God’s calling. Sometimes it is, but often it is not. Callings should almost never be chosen on the basis of pecuniary considerations alone. Rather, we should ask, Where can I best place my salvation on display? How can I best show people God’s love by serving them? What am I equipped to do with excellence, and what will make the greatest difference for the Lord?

A man who would make a terrible pastor might make a wonderful truck driver. A woman who could never adapt to the mission field might make a good lawyer. Some young people who would be miserable in college might be more useful—and more happy—as plumbers or electricians. God not only calls people to different vocations, He also equips them differently for those vocations.

Every vocation deserves respect and even esteem. Christians who are farmers, bankers, doctors, airline pilots, police officers, short order cooks, managers, cashiers, actuaries, and stay-at-home moms have vocations that are just as significant to God as the vocation of the minister. Let us honor all, and make the most of the callings that God has given us.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Psalm 82

Isaac Watts (1674-1748)

Among th’ assemblies of the great

A greater Ruler takes his seat;

The God of heav’n, as Judge, surveys

Those gods on earth, and all their ways.

Why will ye, then, frame wicked laws?

Or why support th’ unrighteous cause?

When will ye once defend the poor,

That sinners vex the saints no more?

They know not, Lord, nor will they know;

Dark are the ways in which they go;

Their name of earthly gods is vain,

For they shall fall and die like men.

Arise, O Lord, and let thy Son

Possess his universal throne,

And rule the nations with his rod;

He is our Judge, and he our God.

Blessings of Distance Education

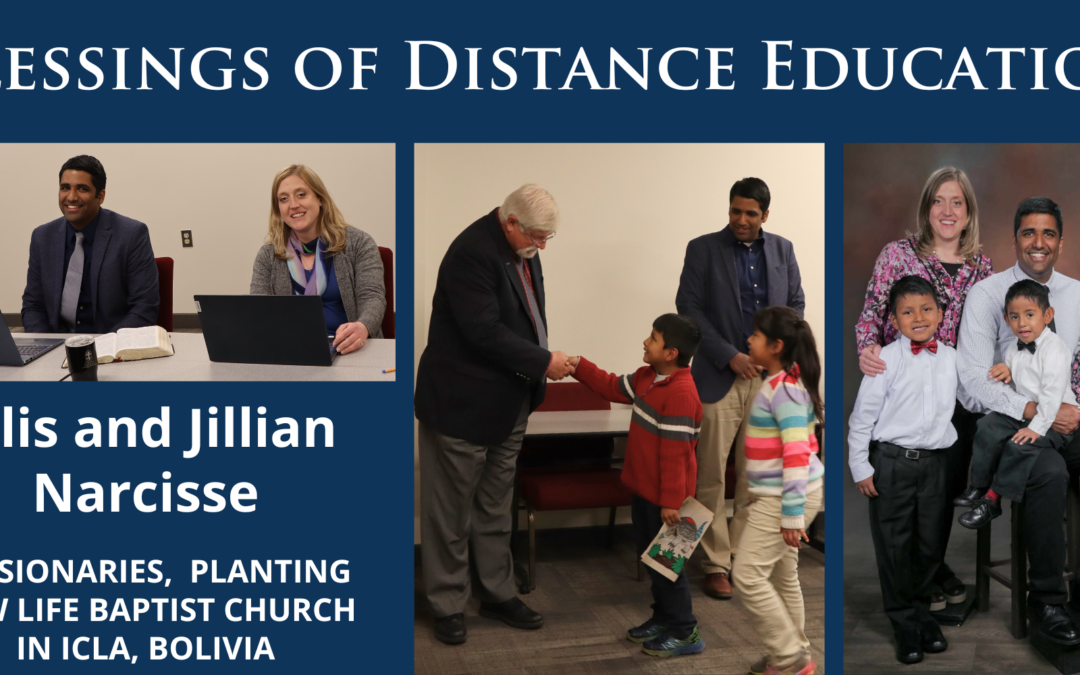

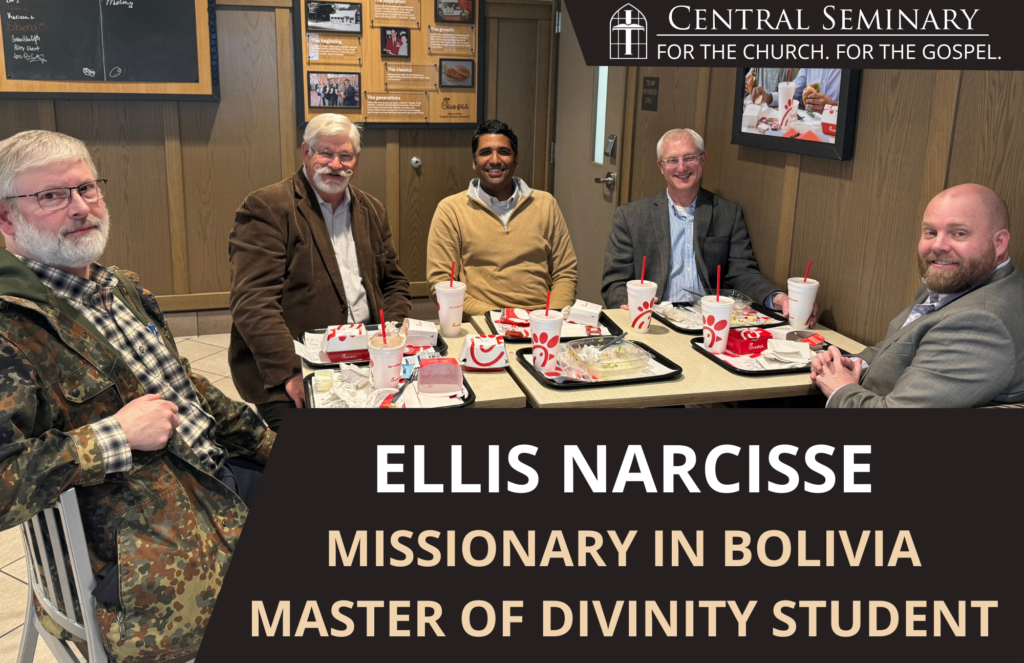

This week, Central Seminary welcomed Ellis and Jillian Narcisse, distance education students from South America, to spend some time at our campus in Plymouth. The Narcisse family, along with their three children, are missionaries in Bolivia planting New Life Baptist Church. Their visit to Central Seminary coincides with a family visit to North America this spring and summer.

The global pandemic of Covid-19 opened doors for the Narcisse family in an unexpected way. Cell service became available for the school system in their remote village high in the Andes mountains. This newfound connectivity allowed Ellis to begin his Master of Divinity through Central Seminary’s distance education program. Jillian has also joined in, pursuing her M.A. in Biblical Counseling.

Central Seminary faculty and students were thrilled to have the Narcisse family join them on campus for classes. Their dedication to ministry and their commitment to continuing their education, even from afar, is an encourgament in our mission.

To learn more about distance education, visit our Distance Education page.

During the month of April, we are accepting free applications. Look up our programs and begin the process. We would love to assist in your studies of God’s Word.

Libraries and Bookstores

I learned to read in first grade. I loved it immediately. Being able to conjure meaning from black marks on a white page was like magic. I no longer had to rely on others to read stories to me. I could discover for myself what Dick and Jane, Sally and Spot were doing.

An aunt used to bless us with copies of the great children’s books. Together with books that my parents gave us, my siblings and I had whole shelves of reading. These included the Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys mysteries (we read them all, indiscriminate of gender). We had some volumes of the Bobbsey Twins, and I remember reading several Tom Swift books. We had abridged editions of classic literature, and I loved the Landmark historical series.

I must have been in fourth or fifth grade when my parents bought me a book of short stories by Edgar Allan Poe. That introduced me to horror. Though I did not find Poe particularly frightening, Algernon Blackwood’s short story, The Willows, haunted me for weeks.

It must have been about that time—fifth or sixth grade—that our class went on a field trip to the Sage Library in Bay City, Michigan. The building looked like a castle, and inside were more books than I’d ever seen. Not just shelves of them, but whole rooms and even floors of them. I was enthralled. Sadly, I’ve never been back, but the event began a love affair with libraries.

By the time I was in seventh grade my parents had moved into the small town of Freeland, where I learned that the Saginaw County bookmobile visited every two weeks. I was ecstatic. I received my first library card and, as I recall, this was where I first read Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories about Sherlock Holmes.

Two years later we had relocated to Iowa so my father could attend Bible college. Soon my mother was managing the campus bookstore. I can remember helping my father build sections of bookshelves for the store, some of which may still be in use after fifty years. This was my first contact with a bookstore, and I learned to love the atmosphere of a room filled with books for sale.

Mom’s job also helped my father to build his library. It gave her a line on publishers’ discounts and closeouts. We lived right across the street from the college, and Dad built a study in our basement. Soon it was packed with hundreds of books. I loved to sit at his desk and read his books. For example, Feinberg’s commentary on Ezekiel helped me to understand the opening chapters of that prophecy.

Within another couple of years, Dad had accepted a pastorate in a small town. Now his study was in the church building, and he had even more books. This room was one of my favorite places. Perhaps that is where I first discovered that, even in solitude, one is never alone when one is surrounded by books.

When I was a junior in high school I accompanied my father to a bookstore in downtown Des Moines. He pointed out the writings of C. S. Lewis and encouraged me to get acquainted. He even bought me copies of The Screwtape Letters and Out of the Silent Planet. I could not have guessed what a turning point that day would become.

About that time, indoor shopping malls became the rage. Ames had the one that was closest to our home, but Des Moines had a bigger one. Inside those malls were shops like B. Dalton Booksellers and Walden Books. Later on, Borders Books and Barnes and Noble joined them. For the next twenty years, any trip to the mall meant checking the discount tables in those stores.

When I was in Denver for seminary, one of the big mail-order distributors of theological books had a retail store in the south part of town. Several classmates and I would visit that store to look for bargains every few weeks. It’s where I bought my first copies of many of J. Gresham Machen’s essays. That, too, was a turning point.

During my first pastorate I learned that some of the big publishers operated their own bookstores in Grand Rapids, Michigan. On a couple of occasions I traveled to Grand Rapids specifically to raid the stores at Eerdmans and especially Kregel. They were wonderful places.

When I moved to Dallas for doctoral studies I discovered a Half Price Books just a mile from our home. It wasn’t huge, but it had a surprising selection of used books at good prices. The problem was that I had no money. I recall coveting a volume of Meister Eckhart’s works for something like two years before finally making a lowball offer on it. And my offer was accepted! I went home feeling like a great hunter that day.

Dallas was home to the Half Price Books headquarters. Their main store was located near Central Expressway and Northwest Highway. It was in a rambling old frame building with board staircases leading to the second floor. My children loved it as much as I did, and they would beg to go to the “wooden bookstore.”

Other bookstores were scattered around Dallas, and I got to know most of them. When I was planting a church in Sachse, we had to drive to Plano to copy our bulletins. My wife would make the copies at Office Depot while I took the kids next door to the bookstore. They would be too occupied ever to cause trouble. So was I, sometimes to my wife’s exasperation.

Of course, both my study and my home eventually began to overflow with books. I could see a problem looming—where to find more space for shelves? But then the world changed. By about 2005, Amazon was pushing brick-and-mortar bookstores out of business. By 2010, Kindle and Nook were beginning to replace paper books, and Logos was providing an electronic platform that greatly enhanced theological study. Around 2012 I began to shift seriously toward electronic books.

I still have several thousand physical books, but fewer than I once did. I have more than double the volumes on Logos, and many times more for Kindle. I have begun to cull most physical books if I own an electronic version.

It’s wonderful to be able to transport tens of thousands of volumes in a computer no larger than a clipboard. I love being able to read almost anything I wish, almost anywhere I want to read it. I’m more grateful than I can say.

But I miss bookstores. I miss their atmosphere. I miss the adventure of handling texts before buying them. I miss being able to leaf through the pages. I miss the smell. Sadly, those are experiences that are now receding into the past, and I feel sorry for the coming generations that will miss them.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Rise, O My Soul, Pursue the Path

John Needham (?-1786)

Rise, O my soul, pursue the path

By ancient worthies trod;

Aspiring, view those holy men

Who lived and walked with God.

Though dead, they speak in reason’s ear,

And in example live;

Their faith, and hope, and mighty deeds,

Still fresh instruction give.

‘Twas through the Lamb’s most precious blood

They conquered every foe;

To His power and matchless grace

Their crowns of life they owe.

Lord, may I ever keep in view

The patterns Thou hast giv’n,

And ne’er forsake the blessèd road

That led them safe to Heaven.

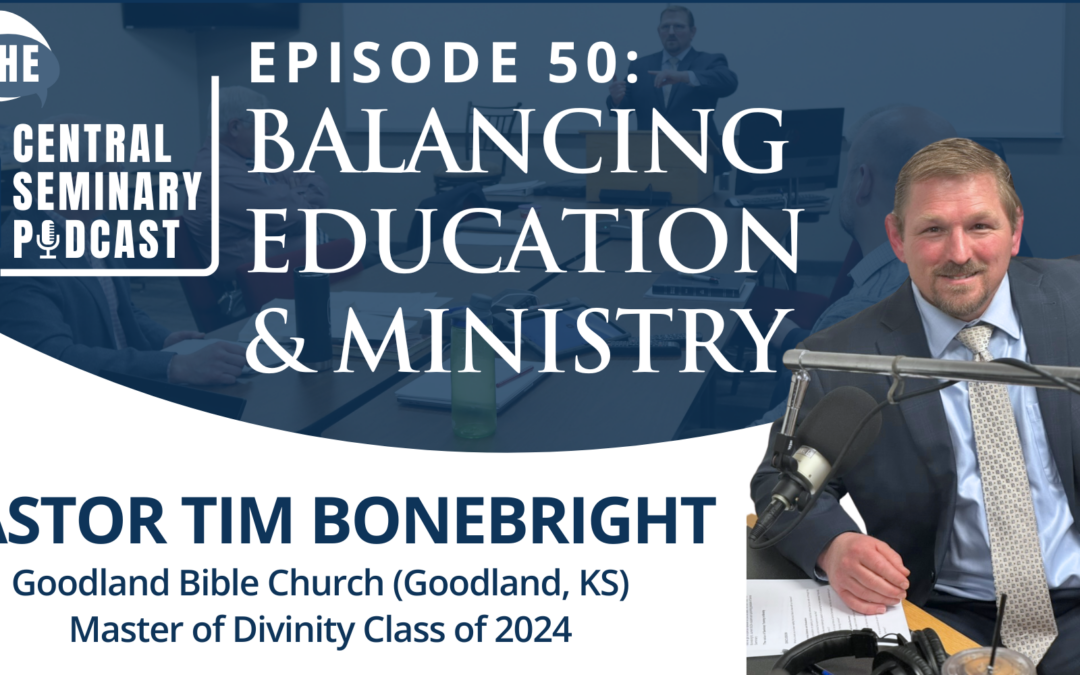

Episode 50 – Balancing Education & Ministry

In today’s episode, we sit down with Pastor Tim Bonebright (M.Div. Class of 2024) to talk about balancing education and ministry. We discuss the process of preparing for the doctrinal defense and how taking classes has supplemented pastoral ministry.

Takeaways

- Preparing for the doctrinal defense starts with each systematic course, gets refined with senior seminar, and with feedback from professors.

- Taking classes at Central Seminary has helped in pastoral ministry, particularly in preaching and clarity of message.

- Pastors can benefit from theological education by gaining a greater understanding of the Bible and being better equipped to answer questions and address challenges.

- Seminary students can engage their minds and disengage from the challenges of ministry, finding refreshment in the study of God’s Word.

- The future of theological education is promising, with opportunities for global connections and the spread of the gospel.

- The professors at Central Seminary invest in their students and provide personal support and guidance.

Book Suggestions

- ‘Share Jesus Without Fear’ by Bill Fay

- ‘Tactics’ by Greg Koukl

- ‘Conversational Evangelism’ by David and Norman Geisler.

Quotes

- Speaking on the doctrinal defense: “Dr. Williams had said, ‘It’s really a celebration.’ And being on this side, I go, yeah, it really is! It really is a time of joy! And looking back (I wouldn’t say this during it) but that was fun because you’re talking theology with men that are godly men that you respect and men that know the Word very well.”

- “And that was phenomenal because now I feel like I’m better able to proclaim the word.”

- “There is the opportunity to learn from people in other continents and to see the ministry that God has given them and they are students of the Word. And I go, wow, I want to be a student like they are.”

- “I think each year I’ve been here, I’ve had different teachers that were my faculty and they would call me during the year just to check on me, just to pray with me.”

- “Look at Central, you won’t find a better school.”

- “It’s hard work, but when you get to this point, it’s worth it. It truly is.”

Full Transcript:

Ep. 50: Balancing Education & Ministry

Micah Tanis, Host

Welcome to the Central Seminary Podcast today. We’re glad you have joined us. We’ve got a special episode for you this week. This is during the time of our semester when we have our graduating students come in for their doctrinal defenses. We just had a Doctor of Ministry defense with Mark Herbster and a really neat time to go through that. We are currently in the time of going through our senior MDiv students. And I’ve got one of our senior MDiv students with us here in the podcast studio, Pastor Tim Bonebright.

Pastor Tim, Thank you and welcome to the podcast.

Tim Bonebright

Well, thank you Micah. It is great to be here It’s a joy to be on campus

MT: Yeah, and there’s a little extra joy in your voice today Tim because just just an hour and a half ago Tim Successfully defended his doctrinal defense. So congratulations Tim I’m sure that’s a weight off your shoulders?

TB: It very much is now I just have to finish up the last few classes and get back here for graduation

MT: So it’s great to have Tim on campus here because right now Tim is pastoring and Tim is pastoring in Kansas, I understand. What’s your church? Tell us just a little bit about your church in Kansas.

TB: Yeah, it’s Goodland Bible Church in Goodland, Kansas. Goodland is 17 miles across the Colorado -Kansas border, a little farm community. It’s a church of 60 to 70 people if everyone was there. Just a neat little church with some wonderful people there that love the Lord. We’re not a perfect church, but there’s just some dear people there that I love being able to serve with.

MT: And how long you’ve been pastoring there, Goodland?

TB: Coming up in June, it’ll be nine years. Excellent, yes. I accepted the call there in June of 2015 and moved there in July of 2015.

MT: We’ve got Tim here to just share a little bit about some of the events and the ways that some of our students go through the semester. Even this doctrinal defense, what is that? Is it like ordination? And it’s a neat opportunity. And so we’re going to ask some of those questions, but really what I wanted to bring Tim here to ask him some questions about how taking classes has supplemented pastoral ministry.

We’re going to get into that topic a little bit today on our podcast as we come here to think about how God is using His word and that deep study of it to supplement pastoral ministry. So first talking about the defense because that’s just what was happening today.

What was some of the preparation for that doctrinal defense?

How did you prepare the documents necessary for that? What was that process for you?

TB: Well, as a student, you go through the systematic classes, but what you do as a senior is there’s a Senior Seminar that Dr. Brett Williams leads, and each week you present a different area of systematic theology, and you talk through it, and then he sends it back to you with comments on it, and then after the semester, you put it all together, you make the changes that are necessary or that he recommends, and then you send it back to him.

And then he has a few more comments. And once that’s done, it’s given to the, to the professors and you show up to, for them to question you, but it’s, it’s actually a very, a longer process than just what I said, but it’s a very helpful process. Dr. Williams does a great job of engaging the seniors and helping them not necessarily trying to change what they think, but to sharpen it and, and help them to kind of formulate how they, how they, how they think in a way that’s, that’s clear and concise and able to be presented not just in a doctrinal statement but to the teachers as you defend the doctrinal statement.

MT: Going through the process as you just went through that today about two hours, maybe just some of your thoughts as you were going through and presenting that. I understand you’ve gone through ordination so you’ve pursued that process and then now with a doctrinal defense just fielding some of the questions. What was that similar to Sunday school? Teaching, pastoring?

TB: Yes, in some ways in that you get questions but the difference is in Sunday school, there are people looking to you for the answer that they don’t know. In this situation, they’re looking for the answer that they know and they want to hear your answer. And so it’s similar to ordination, but it’s a bit different because it’s with the teachers, the professors here, it really is a time of learning.

And what I found helpful is they started out and I was expecting to be grilled and just immediately out of the gate, just question after question, just rapid fire, kind of how ordination sometimes can be, but it was, they explained the first doctrine theology proper, gave a short concise statement of my statement, and first moment there was silence. But then instead of asking questions, they looked at something, well consider this, and consider this, and not that there wasn’t questions, but it was walking me through things, and if there was something that maybe I wasn’t a little clear on, they would actually ask me questions in a way that would help me to get to an answer and that they suspected I had.

And so that was very helpful because

it was Dr. Williams that said, it’s really a celebration. And being on this side, I go, yeah, it really is. It really is a time of joy. And looking back, I wouldn’t say this during it, but look back and go, that was fun because you’re talking theology with men that are godly, men that you respect, and men that know the Word very well.

MT: I want to get into the meat of our conversation today to talk about how that has equipped you or it was right along with the process of pastoring. So taking your classes, how has taking the classes at Central Seminary been helpful in your pastoral ministry because you’ve been doing both for these many years?

TB: Yeah. Well, it’s funny you asked that because I started at Central because I had gotten on at Goodland Bible and I was growing. And I was at the place in life where I realized I don’t have all the time in the world. Because when you’re 20 and 30, you’re going, OK, I got a lot of time. But then as you get closer to 40, you go, I need to speed up this process. And so I knew Dr. Pratt from Maranatha where I went to college. And I really respect him and connected with him at a convention and said, that’s where I want to be because they had a distance program. And it’s been very helpful because Central isn’t a seminary that is easy but it’s also a seminary that wants to help pastors and wants to help people in ministry. And so they will engage you and engage your mind and challenge you, but they also want you to be successful in ministry. For the church, for the gospel is truly a line that not just is on the slogan, but is what Central does. So it was very beneficial and kind of a broad scope in this side of it six years later that it just, it just, it prepared me in ways for ministry, for pastoring. And I can get into more of that as we get into that.

Central isn’t a seminary that is easy but it’s also a seminary that wants to help pastors and wants to help people in ministry.

MT: Speaking, thinking of your church family, what are some of the benefits they’ve received of you being in seminary? I know that can be a balance and we’ll talk about that in a few moments, but what are some of the things that they get to take some of the classes alongside you, meaning you’re taking a class and then you get to maybe teach on that right away the next semester or next year?

TB: Yeah. Well, like part of it, again, big picture is a greater understanding. I’d taken Greek in college and then I didn’t use it and then I retook it here and incorporated that into my study. And then with Expository Preaching with Dr. Odens, he’s one of the best homileticians in the world if you were asking me. And so I feel like right now I’m at a place where I’m getting kind of all these things coming together where now when I preach I feel like I’m much more focused and even my wife will tell me that it wasn’t bad before but there’s the direction is better.

And so I get as far as for my church, I think there is better clarity in the preaching because now I’ve got the proposition, I’ve got the main points that connect to the proposition, or that’s the goal in preaching. And whereas before I didn’t think about that as much, alliteration was important, but which it’s not that important. A good proposition and good main points are far better than alliteration. So that has been beneficial.

We could say that that there’s times where maybe I do a paper and then I can teach on that. In fact, there was a paper that Dr. Bowder asked the question of, is homosexuality ever allowable? And so I normally don’t teach Sunday School, but there was one week I did and I said, well, I can do a regular lesson or we can answer this question and I’ll let you guys vote. And they voted on that. So we had a good hour conversation because somebody could say, well, no, move on. Well, okay, we agree with that, but… Why? Because these are questions that, and I even said, your kids and your grandkids are being brought to their attention, because there are some people that are presenting ideas that are really capturing hearts and minds, and they’re going, okay, yeah, well, how do we respond? And I couldn’t have done that had I not been in… Well, I could have, but being here at Central made it a lot easier.

MT: Being a pastor, down in Kansas, what were some of the formats of classes that you took to complete your MDiv. Were you pretty much all online? Were you able to take in a week modular? How did you take the classes to finish your degree?

TB: Through Zoom mostly. I was here one time for a modular in the fall of, spring of ‘19, excuse me. My goal was to be here on campus more, but life and family and kids happened. And so COVID. Well, COVID happened, but you got to take the classes. Yeah. The nice thing about Zoom is if you are in ministry, you can get a top-notch education and still be involved in your ministry. The bad thing about it is you don’t, once class ends and they click close on the Zoom room, you’re done. And so you don’t get that interaction, which is a part of seminary that is helpful, but not necessary.

MT: Speaking of that interaction, what are some of the ones, and just even talking with the professors, I would hear your name come up, especially my office right next to Dr. Pratt, so I’d hear your name up. What were some of the interactions that you were able to continue? I understand you had even Dr. Pratt down to your church. How were you able to get some of that interaction as a pastor?

TB: Well, one of the wonderful things is that I’m a firm, let’s say, believer in Central, but I very much appreciative of Central Seminary and the ministry here because you get teachers that are, like I said earlier, very knowledgeable. They’re godly people, but they invest in the students. And so as my teachers, they would interact with me. If I were to call them and have a question or want to talk through things, they are available for their students. They will stop what they’re doing if they’re able to engage with you. If they’re not, they’ll get back with you and they will.

They’re there for you in a way that I haven’t seen in any school that I’ve been a part of. And they treat you as one of them. And that’s really an incredible thing because these are people that I look up to, that I appreciate and have great respect for. They treat me as a friend.

MT: You spoke about the strength of the study, the rigor of that study. How did you balance that? You’ve got a personal life and anybody that would be looking or pursuing to take a class. You’re also a pastor too. How did you balance those parts of learning and pastoring and family? How did you learn in that balance?

TB: Well, with great difficulty and sometimes not too well. But it’s one of those things, whether you’re in seminary, there’s always the ebb and flow of life. And so what I would, how I would do that is some nights would stay up after the family would go to bed and do some reading. And so there were some nights that I didn’t get as much sleep. And then, how can I say, I compartmentalize where I have, okay, certain days I’m gonna work on this, and then this day I’m gonna work on this. And so, because a lot of times what it would be is there was one semester that had a lot of work.

I was in Greek exegesis and Hebrew exegesis at the same time. And that was pretty taxing, but I would, after class on Friday, then put away the seminary stuff. And then at that point, really focus on on church stuff. And but then throughout the week, you’re you’ve got church stuff that you’ve got to do. And then there’s also the you can only do what you can do. Yeah. And so even with seminary, there’s certain things I would like to pursue this further. I just can’t. And so I’ve got I’ve got to preach on Sunday. And that’s more important. And so, again, not too well. I didn’t do this too well, but I told my wife I’d rather succeed as a pastor than as a seminary student because I’m a pastor before I’m a seminary student, but the seminary student is to help me as a pastor. And so sometimes I probably should have put the seminary stuff away sooner, but one of the things that I like about being a seminary student is you can engage your mind that way. And ministry’s hard sometimes, and seminary allows you to kind of disengage. Maybe it’s wrong for me to say that, but it’s so you have to be careful that you don’t disengage what God has called you to do for something that is there to help you in your calling.

MT: If you were giving advice to a student sort of like yourself, maybe looking even back at yourself who’s going into a pastorate and saying hey, I don’t know if I can start this what if I’m gonna pursue it What advice would you give somebody? Pursuing a master’s degree a master’s divinity. What what would you tell them?

TB: I would tell them do it. But as you start maybe start slow. Kind of get your feet wet to where you start it and then you’ll see that you can do this and that if they were here at Central, they have people there to help them along the way. It’s not that somebody’s pushing you into the deep end and saying, well, we’re gonna see if you can sink or swim. It’s like they’re there with you, kind of walking with you to help you through this process. And so I’d say do it. And then I would say, get from it what you can and that take advantage of the opportunity because it is a wonderful opportunity.

MT: Do you remember any turning points in your seminary education where it started to maybe even take the next step or just defining moments through the time that you were taking the classes?

TB: Yeah, I think one of them was when I did the first year Greek and didn’t really necessarily incorporate that into my study, but then as you get into syntax, you’re now able to start incorporating it into your study and to where you’re looking at, okay, this is this part of speech, but how’s it functioning? And then you’re learning the diagram and different things like that that a lot of people are going, okay, I don’t want to do that, but when you’re studying the word of God to preach and you’re seeing how God’s word is, what the writer is saying and you’re able to get it and in starting to do that, was able to start to see how, OK, this is how this, this what the main point is, and here’s how he’s doing that.

And then so that to me was a turning point, because now I’m incorporating on a weekly basis what I’m learning here. And then with finishing up that and then taking the expository preaching where we’re now I’m getting how I can take this Greek that I’ve learned and now turn it into to a sermon. And that those were two kind of defining moments for me that I’m applying what I’ve learned on a weekly, daily basis.

And that was phenomenal because now I feel like I’m better able to proclaim the word.

MT: Going back to your church, what are some things you’re excited about in the next year or two in your ministry? One, not having classes probably, but the opportunity to, hey, completing it. What are some things you’re looking for with just with your church family?

TB: I think an element that I’m looking forward to is having some more time freed up to engage in some things with the people that I wasn’t able to do. Because if you’re going to do this, you do have to block out times. You have to be more structured in your schedule. But I think there are some things I’m already thinking through of how can I engage the people in a way that I wasn’t necessarily able to while in classes. And just to whether it’s have them over to my house more or just some different ideas that I have of fellowship with the people because churches need that.

MT: What are some of the things that excite you about shepherding the congregation that you’re excited about? It’s our world can look at all of the news cycle. Everything is. We open our newspapers today. What are some things that excite you about pastoring?

TB: To be able to walk with people and see when they make, I don’t want to say connections, but when the word of God at times comes alive, where, I don’t know, comes alive would be the right word, but where they have that moment where they just go, I get it. And you see the changes that they make or you’re able to walk with them and be with them.

And then also another thing that excites me is to be able to learn from them because we often here we’re at Central Seminary and there’s some really smart people here. But one of the things that’s refreshing about ministry, these are people that are just faithfully serving the Lord. And to be able to just do life with them and do ministry is a joy. And like my church, they want to do a workday at my house here in a couple of weeks. And it’s just to be able to love people and be loved by them in something deeper than sports, but something eternal is, there’s nothing better. Nothing better.

MT: Being down in Kansas, you mentioned just a few miles from the Colorado border. What does some of the fellowship that you look like with other pastors, how are you able to rub shoulders with other pastors that around? It’s a neat opportunity. I’ve heard you mentioned some of those ones that Dr. Pratt, you got to run into him. How do you pursue some of that fellowship out in Kansas?

TB: My church is part of what’s called the IFCA International. And so they have regional meetings. The difficulty for me right now is we’re several hundred miles away from any like-minded church, whether it’s the IFCA or a like-minded Baptist church, something along those lines. And so there is some difficulty. And I haven’t been able to go to the regionals like I used to because I have a younger family and then being in seminary. But when I can, I do that.

And there’s different pastors that text me on Sunday mornings telling me they’re praying for me and things like that. And then also one of the things that has been beneficial about being at Central is the engagement that Central really tries. They’ve had to rethink this with Zoom, with a lot of students not being on campus, but how can they engage the students though they’re not here on campus? And so I’ve had good fellowship with these, the teachers and I’m able to call them and talk through a problem or they’ll pray with me when I’m going through some hardships. And that’s been helpful.

So as far as in my local area, there’s other pastors that are believers, but there’s some doctrinal differences that are, the gaps are pretty big. I’m friends with them, but it’s different than somebody like you or people here at Central where I know that I’m aligned with them pretty much. I’m not gonna say 100 % very close in a lot of things.

MT: I want to ask you about just the preparation that God has put you through to bring you to the point of pastoring and what are some of the unique ways that God shaped your life to be a pastor? That if I went back to 12-year-old Tim and told him, hey, you’d be here in 2024 just finishing up a doctrinal defense, what would you have believed yourself?

TB: I would have not. Oh. The funny thing is when I was a kid I was very shy. And I tell people that and they go, I don’t believe this. Ask my mom. I was incredibly shy and kind of give you the history. When I got to high school I started wrestling and I loved it and did well with it. And then God has used wrestling in a lot of ways to direct my steps. It got me to Maranatha where I met you as a boy and we had lunch early.

MT: And tried to talk me into the wrestling team at my high school. I didn’t do it, no.

TB: And then I moved to Colorado to do some wrestling and be involved there and I coached at a high school and went through some hard times and God had to humble me. Pride is something that unfortunately I still deal with. I tell my kids that you’ll be dealing with that till the day you die. Yeah, you don’t graduate from that. God had to break me and I was coaching at a high school and it was really God used coaching at the high school to kind of get me to a place where to recognize this is what God has for me. I’m called to serve him and engage and invest in people. And I was able to do that at the high school with the kids I coached, which ended up at a church in Colorado Springs. My pastor there was somebody I wanted to work under, Jeff Anderson, and got to work under him. And then it was a two-year position to get me to go to Goodland and then well, not that I thought I was going to go to Goodland, but the funny thing is, a year before I went to Goodland, he had mentioned Goodland Bible Church and I said, not going to Kansas. So here I am. Yeah. Yeah. And now you claim Kansas. I claim Kansas. I grew up in California. I don’t claim California. I claim Kansas.

MT: What are your thoughts on the future of theological education? You’ve seen a shift from both taking an undergrad, Maranatha like I did as well, and then having the opportunity to take some of these synchronous courses and doing that. What are some things you see about the future of theological education?

TB: Well, I’m excited and encouraged because of the open doors that people have. One of the exciting things about being a student here at Central is I’ve got classmates in Africa. And initially I thought, well, this is great that Central can be a blessing to these pastors in Africa. And it didn’t take me but a day or two to go, no, these guys are a blessing to us. This guy’s a blessing to me. And so there is the opportunity to learn from people in other continents and to see the ministry that God has given them and they are students of the Word. And I go, wow, I want to be a student like they are. So there’s encouragement that I have. It’s encouragement for me personally that I was able to do this. And then there’s down the road to continue here at Central and some of the other opportunities they have here. And so it’s, I’m excited for the future with this.

And one of the exciting things is it’s just another avenue for the word of God to get out. I love one of my favorite verses is where Paul says the gospel cannot be changed. And one of the exciting things, one of the things I enjoy about Central is this is just one of the ways that the gospel is moving forward. I get to be a part of it at my church and through the ministry of Central.

MT: I got to step into the very end of your doctrinal defense, really, when they were congratulating you that, Tim, you passed. And we’re glad to say that. And as it was really sweet to hear you just share some of the impact that the professors had had on you, what are some of maybe those professors or those moments that they took that just had a deep impact in your life of just stepping into you and walking with you in ministry?

TB: Yeah, it’s just Dr. Pratt when I reconnected with him at the ISA convention, just first thing he says to me is, Dr. Pratt, he says, Tim, call me John. I said, yes, Dr. Pratt. And just the engagement as a friend, as a fellow believer and as a friend, as an equal was just as, well, it’s funny because at the convention, I reverted back to a 21-year-old kid because he was my college teacher where I’ve got to sit straight up. My wife’s sitting next to me. She’s cracking up. I’m not doing what I normally do. I’m sitting still. But it’s just the fact that he treated me as a friend, or there was a time where every class period they’ll start with prayer, and sometimes they’ll say any prayer requests.

And so I can give personal requests, I can give pastoral requests, and there was one time where in church history I just said, pray for me, there’s a situation. And after class I was able to call Dr. Shrader who taught the class and explain him a little more. He said, I’m meeting with the other teachers, and we will pray for you. And then in dealing with that there’s times where you get uneasy, and I was able to call him and he prayed with me. And so they are there for you to take your calls not just on hey, I got a question on this academic issue, but I’ve got this personal issue or I’ve got this pastoral issue and I just need some counsel. I need some help. And so each teacher here, even the adjunct professors, they will connect with you on a personal level and just engage you as a person, which is very important.

MT: It’s a sweet thing to see how students are able to come together. One of the things you guys have is a small group where you get to meet with a professor every so often. What are those like, just some of those small groups where you’re meeting with a professor, who is your maybe small group leader right now? And then what does that look like to get to be in that small group?

TB: My small group leader now is Dr. Bruffey. He’s the first-year Greek teacher, the librarian, and then the Registrar. And Dr. Bruffey is a unique and wonderful man. And so when we meet with him, we get there and he just says, I’ve got no agenda. Let’s just talk. And so you just get to talk. You can talk about ministry. And there’s times where it does get into academic. He goes, I’m trying to stay away from that, but you know, you take it where you want to.

And so you can and then kind of tell where you’re at in life and ministry and then just and I think he tries to connect individually with each student because I remember after one class we talked about connecting and after one meeting he just we just both stayed on and he visited with me for 20 -30 minutes. Excellent. And so that’s because I think each year I’ve been here, I’ve had different teachers that were my faculty and they would call me during the year just to check on me, just to pray with me. And that was very, that was nice. That’s nice. That’s good. Something that we love to ask in the podcast as we have our guests on is maybe a book that has been helpful to you. Recently, I know you’ve read a lot, so you’ve been studying, so you don’t have to pick a textbook. But Tim, has there been a book that has been a particular encouragement to you, maybe one you’re chewing on that you just want to share with our listeners? Maybe they haven’t picked up, maybe they know about it.

Yeah, one of the classes I’m finishing up this semester is personal evangelism and world missions. And there’s several books that Dr. Jeff Brown has us read. He’s an adjunct professor, is dealing with evangelism. And so there’s a couple books he had us read that had been helpful. One was Bill Fay “Share Jesus Without Fear.” And one of the things that was encouraging in that book that Bill Fay talked about is that the responsibility is to share the gospel. And we always worry about, well, will I say the right thing? Will I do it the right way? And he says the only wrong thing is not to share the gospel. Take those opportunities.

Another book in that class was Greg Koukl’s “Tactics.” And one of the things I appreciated about that is how he approaches it by asking questions. And that we’re actually, having done this evangelism, we are, in my church, doing evangelism now. In Sunday school, we’re actually going through Tactics by Koukl and then I’ve been I’m dealing with the Lord’s Prayer and we’re going to move into doing some messages on evangelism Which I added that to it because I thought well, this is I want to do this.

And then I also read recently was David and Norman Geisler’s “Conversational Evangelism” and so those were good books to read because they give you ideas on how to share the gospel and one of the things I think sometimes we get, we feel like we have to do the whole work in one setting. And one of the things they’ll talk about is it’s, you might just be able to, as Coco says, put a stone in their shoe. And if that’s what you do, that’s good because then the next person can come. And so it’s to do your part and to engage them. And it’s been fun to do that because I’ve been able to have opportunities to where I have been able to share the gospel and I’ve seen the challenge that I’ve had to overcome and sometimes I’ve failed but then because I failed here the next time I make sure and I actually was able to at the nursing home there was a man that said I thought I was a goner last night and I sat down and I said well I want to talk to you about something and I explained to him the gospel like hey I want to know that you know I want you to know that you’re going to be with the Lord when you die and I said I want this friendship to last a long time but and I explained to him the gospel about, hey, you’re a sinner and Jesus is the Savior. Put your faith in Him, believe in Him, trust in Him to forgive you. And he prayed and said, God, forgive me for the wicked things that I’ve done. So I said, well, amen. So I… And earlier that day, the plumber is at my house and he told me about a heart attack and I was able to talk a little bit about Jesus, but I didn’t share the gospel. And I went to the nursing home and I said, I’m not gonna fail here. I’m gonna get it done. And when that opportunity presented, I said, I’m not blowing it here. Having read those books, I was ready. I was ready to engage this man.