Theology Central

Theology Central exists as a place of conversation and information for faculty and friends of Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Posts include seminary news, information, and opinion pieces about ministry, theology, and scholarship.

The Man Who Loved Both Doc And Cedar

Not many people could say that they had a close personal relationship with and were mentored by R. V. Clearwaters and B. Myron Cedarholm, but Gerry Carlson could.

Gerald Bruce Carlson was born August 17, 1941 to Dr. George and Evelyn Carlson in Chicago where his father pastored Tabernacle Baptist Church, the very church where the Conservative Baptist Movement held its organizing meeting in 1943. When Gerry was five years old, his family moved to Minneapolis so that his father could assume the pastorate at Lake Harriet Baptist Church and also teach part-time at Northwestern Theological Seminary alongside the seminary dean, R. V. Clearwaters. George Carlson and R. V. Clearwaters were close allies in the first decade of the fledgling Conservative Baptist movement as they served together on various local and national boards and committees. George served as the president of the Minnesota Baptist Convention and as Vice-President of the Conservative Baptist Association.

Gerry loved living in beautiful southwest Minneapolis, and it was quite a jolt to the serenity he enjoyed there when his father accepted a call to the Marquette Manor Baptist Church on the southwest side of Chicago in 1954. But an even greater shock to Gerry, his mother, and his three sisters came three years later in 1957 when his dad was killed in a plane crash as he was headed to Canada on a hunting trip. A man Gerry affectionally called “Uncle Myron” broke the tragic news to Gerry in the living room of his family’s parsonage.

Myron Cedarholm would also preach at George Carlson’s funeral in what Gerry refers to as “the greatest gospel service I have ever known” (unpublished paper, “Doc and Cedar,” 7, March 2017). Gerry’s relationship with the Cedarholms began early in his life as his family would stay with them every summer at their cabin on Lake Nebagamon in northwest Wisconsin, and “Cedar” (as Gerry would refer to him in his adult years) became “somewhat of a surrogate father” to Gerry in the years following his dad’s untimely death.

After Gerry graduated from high school in Chicago, he attended Pillsbury Baptist Bible College where he earned a bachelor’s degree in Bible and Pastorology in 1963. During his college years he served as a youth leader at Fourth Baptist Church in Minneapolis, and it was here that Gerry met his future wife, Connie. They were married in 1965, and their wedding ceremony was conducted by their pastor, Doc Clearwaters. The Lord would bless Gerry and Connie with three children and four grandchildren during their 58 years together.

Upon graduation from Pillsbury, Gerry and many of the other future pastors who had commenced with him traveled north 65 miles to attend Central Seminary. After receiving his M.Div. degree from Central Seminary in 1967, Gerry accepted a call to serve as youth pastor at Calvary Baptist Church in Normal, Illinois, where his friend, Bud Weniger, was pastor.

Gerry’s time in Normal was anything but normal in the wider world of northern Baptist fundamentalism as the Conservative Baptist movement splintered and as different views of educational leadership strategy affected schools like Pillsbury College. Gerry was on the Pillsbury campus for College Days with his youth group in May 1968, just three days after Myron Cedarholm had resigned, and he stayed in the Cedarholm’s Presidential House (where Cedar had been confined by the board in “house arrest,” as some referred to it). Four weeks later, Myron Cedarholm participated in Gerry’s ordination service in Normal, and Cedarholm took the occasion to make the first public announcement that Maranatha Baptist Bible College would be starting up that fall (personal email to author, July 17, 2009).

Gerry would minister in Normal for three years before returning to Minnesota in 1970 to take the pastorate at the newly planted Faith Baptist Church of St. Paul. He spent eight years there and then moved on to work for the American Association of Christian Schools from 1978–1988. He served as both Field Director and Executive Director. Two items of note occurred during these years: 1) Gerry received the honorary Doctor of Divinity from Maranatha in 1983, and 2) Gerry was invited to speak at Central chapel in 1986 with Doc Clearwaters in attendance from whom he received a warm welcome. Commenting on this last point, Gerry later wrote that “time can heal wounds and I was glad for that” (“Doc and Cedar,” 17).

God’s next appointment for Gerry was the position of Vice President at Maranatha Baptist Bible College, where he served from 1988–1994. It is likely due to his 16 years of educational experience with AACS and Maranatha that led the board of Pillsbury Baptist Bible College to appoint Gerry as the sixth president of the institution in 1994. But his tenure at his alma mater would last only one year.

In a short book Gerry wrote about his stint at Pillsbury (What Happened at Pillsbury? [Nystrom, 1996]), he explained why he experienced great frustration with the faculty who did not want to head in the same philosophical direction that he (and the board) felt the school should go. In an email to me, Gerry described his one-year presidency as “my suicide mission” (email to author, July 1, 2009). I think it is fair to say the knot of difficulties Carlson experienced in that one-year stint were many years in the making and far too complex for anyone to untie in the short amount of time the board and faculty desired.

Leaving Minnesota for good, Gerry joined the staff at Positive Action for Christ in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. He would work with this ministry longer than any other in his life while serving as Director of Marketing and Development from 1996–2014.

In 2014 the Carlsons moved to Maranatha Village in Sebring, Florida, where Gerry helped with marketing and development for the retirement community up until the Lord took him home on January 30, 2024.

The Lord used Gerry Carlson in pastoral ministry (13 years) and Christian education (35 years). His labors in Christian education included serving on the administrations of two Bible colleges, providing assistance to Christian schools and colleges in his work for AACS, and promoting the publication and distribution of Bible curriculum for churches and Christian schools. His mentors included significant figures in the Conservative Baptist movement. These men included his father, George, his father’s ally and friend, Doc Clearwaters, and his “surrogate father,” Uncle Myron. I believe all three men would be greatly encouraged by who their mentee became: a faithful and kind friend to many, a loving husband and father to his family, and a fruitful and diligent servant in the Lord’s harvest field.

![]()

This essay is by Jon Pratt, Vice President of Academics and Professor of New Testament at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

May the Grace of Christ Our Savior

John Newton (1725–1807)

May the grace of Christ our Savior

and the Father’s boundless love,

with the Holy Spirit’s favor,

rest upon us from above.

Thus may we abide in union

with each other and the Lord,

and possess in sweet communion

joys which earth cannot afford.

Larry Pettegrew (1943–2024): A Life Lived to the Glory of God

One of the favorite books in my library is a festschrift written in honor of Larry Pettegrew (published by Shepherds Press in 2022). I value it so highly not because of its content (though the 14 essays are certainly noteworthy) but because of the personal note of thanks Larry wrote to me on the title page. One sentence stood out to me: “We’ve been friends for a long time, and your faithful ministry has been a blessing and encouragement to me.” This sort of Barnabas-like behavior was so typical of Larry; he had the knack of saying the very things to you that you wished you would have said to him first.

Larry Pettegrew was born and raised in Danville, Illinois. His home church was First Baptist Church, where he met his wife Linda in junior high. They were married in 1966, the year after he graduated from Bob Jones University with a Bachelor of Arts degree. God blessed their union with three children and eight grandchildren, and 2023 marked 57 years together.

After college Larry moved to Minnesota so he could attend Central Seminary, where he earned the M.R.E., M.Div., and Th.M. degrees. In 1968 Larry began his teaching ministry, which would span more than 50 years. He would serve on the faculty at Pillsbury Baptist Bible College until 1980 as the head of the Christian Education and Bible departments. During his time at Pillsbury, Larry earned the Th.D. degree in Historical Theology from Dallas Theological Seminary in 1976. His dissertation on the Niagara Bible Conference is still considered the best resource available on the significant contribution that annual gathering provided for dispensational theology.

From 1980–1995 (with the exception of one year) Larry served in several capacities at Central Seminary: professor of systematic and historical theology, registrar, and academic dean. After his first year at Central, Larry moved to Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary, where he would teach for only one year (1981–1982) before coming back to Central. It seems the main impetus behind Larry’s return to Central was the encouragement of his friend, Doug McLachlan, who was the newly installed pastor of Fourth Baptist Church and who wanted Larry to assume dean responsibilities at the seminary.

In 1995 the Pettegrews moved to Sun Valley, California where Larry worked as a professor of theology at The Master’s Seminary, a position he would hold for 12 years. At the age of 64, when many might have considered retirement, Larry believed the opportunity to serve as Dean and Executive Vice President for the fledgling Shepherds Theological Seminary in Raleigh, North Carolina, was a challenge too exciting to pass up. So in 2007 Larry’s final professorial position began, and he served there until his death on January 30, 2024. Shepherds’ president and founder Stephen Davey described Larry’s work this way: “[He] set out to graciously and wisely construct the structure of our school. He added trusted faculty members and worked hard with our seminary board as we pursued accreditation.”

Consider with me four aspects of Larry’s ministry that demonstrate his good stewardship of the manifold grace of God evidenced in his life: church ministry, writing, teaching, and mentoring.

Although Larry never held a paid position on a pastoral staff, he certainly loved the church and faithfully served in a local church at every one of his teaching posts. Whether he was teaching adult Sunday School, helping other local churches as interim pastor, or serving as a deacon, Larry left an indelible Christ-shaped impression on his brothers and sisters in the local church.

Besides his dissertation on the Niagara Bible Conference (which appeared in 5 parts in the Central Bible Quarterly [19.4–20.4]), Larry published The History of Pillsbury Baptist Bible College (1981) and The New Covenant Ministry of the Holy Spirit (2013). He also edited and was the main contributor to Forsaking Israel: How It Happened and Why It Matters (2020). Additionally, he wrote numerous journal articles and book essays. His writing was always clear, well-researched, and immensely helpful.

Larry’s teaching ministry was where he shined most brightly. His students would agree that his classroom instruction was marked by his humble demeanor, clear and careful scholarship, and compassionate concern for students. I was one of the students greatly affected by Larry’s willingness to use his God-given gift for instruction and writing. He taught me church history, systematic theology, apologetics, and pedagogy. In acknowledging this I know that thousands of others in ministry today can say the same thing, whether they had Larry as a professor at Pillsbury, Central, Detroit, Master’s, or Shepherds.

One feature of Larry’s ministry that was not as well-known as his other more public activities was his role as a mentor to so many of us. In my case he functioned as a model in many ways. First, he showed me what being a wonderful friend and teaching colleague should look like by the way he interacted with my dad when they worked together on the faculty at Pillsbury. Second, he taught me how to be a seminary professor and Bible teacher by how he exemplified love for God, excellence in the teaching craft, thorough knowledge of his subject, and humble concern for every student. Another discipline Larry demonstrated was prayer for his students. Many years after I had graduated from seminary Larry remarked to me in passing, “I pray for you every Thursday.” While I suspect that he could not have prayed for all of his former students in this way, it buoyed my own spirit significantly that I was on his prayer list, and I have been so affected by Larry’s example that I, too, pray for a long list of former students on a weekly basis. Third, Larry exhibited for me how to be an effective seminary dean. While I caught only glimpses of this as a seminary student, I learned much more in the years after I became the dean at Central in 2010. We attended a dean’s conference together, and even there, I saw him actively taking notes and pursuing ways he could improve in this calling.

Central’s chancellor Doug McLachlan described Larry in an email he sent to him in July 2022: “I believe you, Larry, have fleshed out this [paradigm of the simultaneous expression of holiness and love] admirably in the world of Christian scholarship, both in your proclamation and defense of the truth of God’s Word. Countless students and servants of the Lord have been helped by your commitment to this Christlike paradigm of doing ministry and mission as a theologian…. Larry, it is this virtue especially that has characterized your ministry for a lifetime—approved; no need to be ashamed; a good steward of Holy Scripture; rightly handling the word of truth. We express our gratitude to you for this ‘long obedience in the same direction.’”

I praise the Lord for finding Larry faithful and putting him into the ministry, and I also praise Him for His kind providence in allowing me to study with, learn from, and enjoy the friendship of a man of God like Larry Pettegrew.

![]()

This essay is by Jon Pratt, Vice President of Academics and Professor of New Testament at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

O For a Faith That Will Not Shrink

William Hiley Bathurst (1796–1877)

O for a faith that will not shrink,

Though pressed by every foe,

That will not tremble on the brink

Of any earthly woe.

That will not murmur nor complain

Beneath the chastening rod,

But, in the hour of grief or pain,

Will lean upon its God;

A faith that shines more bright and clear

When tempests rage without:

That when in danger knows no fear,

In darkness feels no doubt;

That bears, unmoved, the world’s dread frown,

Nor heeds the scornful smile;

That seas of trouble cannot drown,

Nor Satan’s arts beguile;

A faith that keeps the narrow way

Till life’s last hour is fled,

And with a pure and heavenly ray

Illumes a dying bed:

Lord, give us such a faith as this;

And then, what e’er may come,

I’ll taste, e’en now, the hallowed bliss

Of an eternal home.

Most Interesting Reading of 2023, Part Three

I must have encountered more interesting books than usual during the past year. At any rate, I’ve never had to take more than two weeks’ worth of In the Nick of Time to list them, but this year I do. As ever, I warn you that just because I found these books interesting does not mean that you will.

Kruger, Michael. Bully Pulpit: Confronting the Problem of Spiritual Abuse in the Church. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2022.

In my experience, the typical book on spiritual abuse boils down to, “My friends and I wanted to live really carnal lives, but a pastor told us it was wrong, so we’re mad.” While spiritual abuse is less common than some pretend, it does happen, and it should never be tolerated. What we need is a responsible approach to diagnosing and treating it by someone who understands that pastoral duty sometimes involves wounding as well as healing. Kruger provides that approach. He is a seminary president with a pastor’s heart who knows and understands the Scriptures, and who can apply them well. This may be the best book on spiritual abuse that I’ve ever read.

McIntire, Carl. Author of Liberty. Collingswood, NJ: Christian Beacon, 1946.

________. Rise of the Tyrant. Collingswood, NJ: Christian Beacon, 1945.

When he published these two volumes, Carl McIntire was the most publicly recognizable fundamentalist in the world. Both books wrestle with the problems of political economy, seeking to provide a biblical and theological underpinning for a Christian response to the problem of free markets versus managed economies. While it is more biblically grounded, McIntire’s approach comes close to that of the Austrian economists which, however, would not be widely known for another decade or so. Ironically, both these books appeared before Carl F. H. Henry’s Uneasy Conscience, where he lambasted fundamentalists for their lack of social and political engagement. Henry certainly knew about McIntire’s work. Perhaps he was simply unwilling to admit that a despised fundamentalist had beaten him to the punch.

Pivek, Holly and R. Douglas Geivett. Counterfeit Kingdom: The Dangers of New Revelation, New Prophets, and New Age Practices in the Church. Nashville: B&H, 2022.

A couple of years back, a friend gave me three books on the New Apostolic Reformation, and I finally got around to reading them this year. While I disagree with Charismatic theology in all its forms, I’ve never gone out of my way to study its variations. Turns out that the NAR is one of the most obnoxious forms, seeking to reintroduce the offices of both prophet and apostle. If Pivek and Geivett are anywhere close to right (and I know Geivett, at least, to be a careful scholar), then the practices that these new prophets and apostles have brought with them are nothing short of bizarre. For an example, run an internet search for “grave sucking.”

Poythress, Vern S. The Mystery of the Trinity: A Trinitarian Approach to the Attributes of God. Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2020.

Everything that Vern Poythress writes is a treat. His style is as clear as polished diamond, and he brings a truly charitable bearing to all his work. In The Mystery of the Trinity he asks whether the traditional doctrine of the Trinity is fully scriptural, or whether it might rely upon some extrabiblical philosophical categories that orthodox theologians have smuggled into their systems. His approach is not to debunk, but to examine. As one might guess, he relies heavily upon Van Tilian philosophical categories into his own perspective—but he knows he is doing it, and he sees it as biblically justified. This is a Big Book, but Poythress handles his topic well.

Ramaswamy, Vivek. Woke: Inc.: Inside Corporate America’s Social Justice Scam. Nashville: Center Street, 2021.

Since I read this book, the author has entered and left the race for the American presidency. Because I had read it, I believed that his campaign made sense. Ramaswamy comes from the corporate world. He is a Person of Indian Origin and a Person of Color. He is a Hindu. None of this exactly positions him within the supposed White Christian Supremacism of the Republican Party. But he also has a keen sense of how unjust social justice can be. He is particularly concerned with the economic results that arise when businesses are more concerned with scoring points for their social consciences than they are with serving their customers. Ramaswamy has left the presidential race, but his book is still well worth a read.

Stroud, Nick. The Vickers Viscount: The World’s First Turboprop Airliner. Barnsley, UK: Frontline, 2018.

I grew up flying on propliners. One of my earliest memories is of leaving the ground while sitting in the window seat of a Douglas DC-3. Over the years I flew on the Douglas DC-4 and DC-6, the Lockheed Constellation, and the Convair 340. Then the jets took over. Much of my childhood flying was on the Vickers Viscount. This was a British design powered by four Rolls Royce turboprop engines. It was quieter and smoother than the piston-driven airliners, and it had big, round windows that allowed a magnificent view. Nobody else will care about this book, but for me it provided a mental journey to a time when flying was comfortable and airlines treated passengers like people instead of cattle.

Trueman, Carl R. Strange New World: How Thinkers and Activists Redefined Identity and Sparked the Sexual Revolution. Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2022.

In 2020, Carl Trueman published The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, a Great Big Book of intellectual history and social criticism. It is a good book, but far too dense for the ordinary person to understand. Two years later he followed it up with the present volume, which covers much of the same territory but does it in a shorter and more simplified format. I’ll put it bluntly: this is one of those books that every pastor and Christian teacher simply must read.

Yuan, Christopher. Holy Sexuality and the Gospel: Sex, Desire, and Relationships Shaped by God’s Grand Story. New York: Multnomah, 2018.

Christopher Yuan’s background was in drugs, gangs, and homosexuality. He came to Christ in prison, went on to seminary, and eventually became a professor at Moody Bible Institute. In this volume he sets discussions of marriage, singleness, homosexuality, and transgenderism within the context of a biblical theology of sex and gender. I now require this book for my course on Creation, Sex, and Gender. It’s another of those books that every pastor should read.

And that’s my book report for this year. Some of these books you’ll like. Some of them, not so much. But if there are any other Viscount fans out there, drop me a note. We can reminisce together.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

O for the Wisdom from Above

James Montgomery (1771–1854)

O for the wisdom from above,

Pure, gentle, peaceable, and mild,

The innocency of the dove,

The meekness of a little child.

Wise may we be to know the truth,

Reveal’d in every Scripture page;

Wise to salvation from our youth,

And wiser grow from stage to stage.

Then if to riper years, we rise,

And well the work of grace be wrought

Within ourselves,—we shall be wise

To teach in turn what we were taught.

Yet still be learning, day by day,

More of God’s Word, God’s way, God’s will;

His law, rejoicing to obey,

Pleas’d His whole pleasure to fulfill,

Wise to win souls, if thus we’re led,

How blest will be our lot below,

Blessings to share, and blessings shed

On all with whom to heaven we go.

So may we reach that home at length,

And, clad in righteousness divine,

Even as the sun, when in his strength,

And as the stars, forever, shine.

Most Interesting Reading of 2023, Part Two

Other people issue lists of the best books they’ve read or of the books that they want to recommend. I compile a list of the books I found most interesting. They are interesting for a variety of reasons, and one of those reasons may be that they are conspicuously bad. Hey, I’m not suggesting you read these books. For whatever reason they held my attention, but they may not hold yours. Or they just might.

Gagnon, Robert. The Bible and Homosexual Practice: Texts and Hermeneutics. Nashville: Abingdon, 2010.

I previously noted that I teach a course on creation, sex, and gender. In that course I deal with the 2SLGBTQIA+ conglomeration (yes, you read that correctly, and I’ll betcha didn’t know about the latest additions to that text string, eh?). Robert Gagnon’s book on The Bible and Homosexual Practice is presently the most comprehensive response to those who insist that Scripture can be read in an accepting and affirming way. I re-read this work periodically, and it was one of the interesting books I read this year.

Ginna, Peter. What Editors Do: The Art, Craft, & Business of Book Editing. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2017.

Having never received formal instruction in writing, I try to make books about writing a staple of my reading diet. The University of Chicago publishes a whole series of related guides for writers, and Ginna’s book is one of that series. The book discusses the many levels and varieties of editing. He describes the road that a book must travel to reach publication, and he explains what editors do at each stage of that journey. He also discusses the advantages and challenges of freelance editing and of self-publishing.

Greyland, Moira. The Last Closet: The Dark Side of Avalon. Kouvola, Finland: Castalia House, 2017.

I hesitate even to mention this book. It is in many respects a good book, but it is a book that deals with a very bad thing, and it pulls no verbal punches in exposing the thing that it deals with. Moira Greyland was the daughter of celebrated author Marion Zimmer Bradley and famed numismatist Walter Breen, both of whom were leaders within gay paganism. The book describes what it was like growing up in their household with all its perversions and abuses. The message of the book is that pedophilia and abuse are hardwired into sexual perversion, including homosexuality. I do NOT recommend this book for most people, but it provides a bracing slap for anyone who thinks that the LGBTQIA+ agenda is harmless. As a counter to the prevailing narrative of acceptance and affirmation, I found Greyland’s story riveting.

Grunenberg, Antonia. Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger: History of a Love. Studies in Continental Thought. Translated by Peg Birmingham et al. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2017.

Martin Heidegger was probably the most influential philosopher of the 20th Century. He was also a Nazi. One of his students—and his lovers—was Hannah Arendt, who was born into a Prussian Jewish family. Arendt would later go on to write whole books condemning the kind of totalitarianism that she witnessed in National Socialism. Yet after the war, somehow Heidegger and Arendt were able to rebuild their friendship, in spite of the fact that she had been forced to flee Hitler’s Germany. Grunenberg explores their mutual intellectual influence and the recovery of their friendship. File this book under Philosophy.

Herriot, James. All Creatures Great and Small. New York: Saint Martin’s, 1972.

All Creatures is the first in a series of more-or-less autobiographical books from an English veterinarian who practiced during the mid-20th Century. I’ve known of the work since it was first published in the 1970s, but I never got around to reading any of it until this year. It is bucolic, gentle, good-humored, and homey. Spending time with this book was just fun. It left me wanting to read the rest of the series.

Hummel, Daniel G. The Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism: How the Evangelical Battle Over End Times Shaped a Nation. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2023.

The Central Seminary faculty read this book together, then discussed it during our annual in-service meeting. While we could quibble with some details, we give full credit to Hummel for his masterful knowledge of the history and varieties of dispensationalism. We particularly appreciate his discussion of the differences between scholarly and popular dispensationalism, as well as his noting the difficulties that scholars encounter in trying to articulate a responsible dispensationalism while the popularizers are making so much noise. Hummel has given us a valuable contribution to the discipline.

Koestler, Arthur. The Thirteenth Tribe. San Pedro, CA: GSG & Associates, 1976.

The thesis of Koestler’s book is that modern Jews—especially Ashkenazi or Eastern European Jews—are not descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel. Instead, they are the offspring of a Japethic kingdom, the Khazars, who flourished in Asia during the Middle Ages. Koestler posits that the entire tribe of Khazars converted to Judaism as a religion, but that their bloodline remains non-Semitic. Notably, Koestler’s work has become popular in certain Anglo-Israelite and White Supremacist circles. These types find in Koestler a basis for denying the Abrahamic blessing to modern Jewish people. Of course, Koestler wrote before DNA sequencing was a thing. DNA analysis has provided no convincing support for his theory.

A thing is about to occur that has never happened before. My list of “most interesting books” is going to have to spill over into a third week. I express my apologies if this isn’t your cup of tea. On the other hand, if your tastes are odd in the same ways that mine are, you may find that the remaining list will be useful.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Blest Are the Pure in Heart

John Keble (1792–1866)

Blest are the pure in heart,

for they shall see our God;

the secret of the Lord is theirs,

their soul is Christ’s abode.

The Lord, who left the heavens

our life and peace to bring,

to dwell in lowliness with men,

their pattern and their King;

Still to the lowly soul

he doth himself impart,

and for his dwelling and his throne

chooseth the pure in heart.

Lord, we thy presence seek;

may ours this blessing be;

give us a pure and lowly heart,

a temple meet for thee.

Most Interesting Reading of 2023, Part One

Every year at about this time I issue disclaimers. The disclaimers attach to a listing of the most interesting reading that I have completed over the preceding year. What the disclaimers state is that (1) interesting isn’t necessarily the same thing as valuable, and (2) what interests me may not interest anybody else. In short, the following titles may indicate nothing more than my own idiosyncrasies. Still, of all the books I read this year, these stand out as the ones that most captured and held my attention.

Beeke, Joel R. (ed). The Beauty and Glory of the Christian Worldview: Puritan Reformed Conference. Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage, 2017.

Once upon a time, when evangelicals held large conferences, they used to collect and publish the addresses in book form. The custom has now been largely abandoned, but that is exactly what Joel Beeke and Puritan Reformed Seminary have done in this volume. It contains the addresses delivered at the seminary’s conference on Christian worldview in August of 2016. I enjoyed this book as a hybrid of theology, biblical studies and devotional writing. It was good for my soul. Special mention should be made of Michael Barrett’s beautiful exposition of Ecclesiastes and of the two essays by Charles Barrett.

Bennett, Jeffrey. What Is Relativity? An Intuitive Introduction to Einstein’s Ideas and Why They Matter. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

My area of expertise—systematic theology—is not exactly one of the STEM disciplines. In the interest of broadening my understanding of the world, however, I try to do a certain amount of reading in the sciences. I picked up Bennett’s book on a whim and found it a delightful explanation of Einstein’s special and general theories of relativity. Bennett has the gift of making difficult ideas understandable for the non-technical mind. While his writing does not make the results of Einstein’s ideas seem any less strange, it does make the ideas themselves more comprehensible, and Bennett helps his readers to understand why those ideas follow from basic assumptions.

Bock, Darrell L. and Daniel B. Wallace. Dethroning Jesus: Exposing Popular Culture’s Quest to Unseat the Biblical Christ. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010.

C. S. Lewis set up the famous trilemma that Jesus must be either a liar, a lunatic, or the Lord. Against Lewis, modern criticism insists that Jesus was none of these. Instead, He was (is) essentially a legend, a mythic character who cannot be known historically. Darrell Bock and Daniel Wallace are both professors of New Testament, specializing respectively in Jesus studies and textual criticism. In this book they offer a thoughtful, well-researched, but highly readable response to the “Jesus is just a legend” position that sees the New Testament as hopelessly corrupt and Christianity as the product of later developments. This is a book that an ordinary Christian can read and enjoy.

Callahan, Patti. Becoming Mrs. Lewis. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2018.

Reading this book was a mistake—literally. I misunderstood its genre, assuming that it was biography, when in fact it is historical fiction. Its value is that the fictional aspects are structured around and faithful to what is known about Joy Davidman, the woman who eventually married C. S. Lewis. If I had realized that it was historical fiction, I would not have read it. But I would have missed an enchanting retelling of the Lewis–Davidman story.

Cleaver, Thomas McKelvey. The Frozen Chosen: The 1st Marine Division and the Battle for the Chosin Reservoir. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2016.

When I was growing up, my best friend’s dad was a sergeant at Wurtsmith Air Force Base. Only later did I learn that he had been in the Marines during the Korean Conflict—the man never talked about that part of his life. Later still I discovered that he was one of the Frozen Chosen who were trapped behind the Chinese lines in bitter, subzero temperatures. This book retells that story from a political and military perspective. It explains the division between the Koreas, the involvement of the Chinese, and the failures of American policy that led to the conflict. It also narrates the near-defeat of American Marines (and some Army) during the battle of the Chosin Reservoir. I don’t read much military history, but this work helped me to understand a conflict that has not been resolved yet.

Cook, Becket. A Change of Affection: A Gay Man’s Incredible Story of Redemption. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2019.

I teach a doctoral course on creation, sex, and gender, which means that I have to do a fair bit of reading in and about LGBTQIA+ topics. I always find it refreshing to come across personal written testimonies from people who have been in that world but who have been reached for Christ. Becket Cook offers such a testimony in this book. His story begins with his success as a set designer in the fashion industry and ends up with him completing a seminary degree and becoming a pastor. Cook’s is a story of genuine conversion by the grace of God.

Doyle, Andrew. The New Puritans: How the Religion of Social Justice Captured the Western World. London, UK: Constable, 2022.

Be warned: the very first line of this book contains a double obscenity. The author is not a Christian and not even very conservative. He is liberal and secular—and therein lies the strength of his appeal. He has become convinced that the current social justice ideology is a new religion and that its adherents are zealous to enforce it throughout their civilization, by extirpating all heretics and unbelievers if necessary. Doyle’s claims seem extreme when he first makes them, but he backs them up with persuasive arguments, evidence, and narratives. I think that this is one of those books that will help conservatives and Christians to understand what the Left is really after.

Dreher, Rod. Live Not By Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents. New York: Sentinel, 2020.

The author is, of course, a well-known conservative. Like Andrew Doyle, he argues that progressivism in its current forms is (false) religion. Unlike Doyle, he sees the best antidote in countervailing, true religion. In this book, Dreher takes his cues from professing Christians and others who survived the totalitarianism of Soviet communism. While there are points worth quibbling, this book provides part of the helpful preparation in which Christians must engage if they are to face a future of tyranny.

Next week I shall continue with my list of “Most Interesting Reading of 2023.” Remember, I’m not necessarily recommending any book that I list here. I’m not saying it’s a good book, or that everything in it is true. It only appears here because I found it interesting.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

That Man Is Blest

Isaac Watts (1674–1748)

That man is blest who, fearing God,

from sin restrains his feet,

who will not stand with wicked men,

who shuns the scorners’ seat.

Yea, blest is he who makes God’s law

his portion and delight,

and meditates upon that law

with gladness day and night.

That man is nourished like a tree

set by the river’s side;

its leaf is green, its fruit is sure,

and thus his works abide.

The wicked, like the driven chaff,

are swept from off the land;

they shall not gather with the just,

nor in the judgment stand.

The LORD will guard the righteous well,

their way to Him is known;

the way of sinners, far from God,

shall surely be o’erthrown.

Erecting the Right Fences in the Right Places, Part Ten: Complementarianism As a Secondary Doctrine

Gavin Ortlund explains his theory of doctrinal triage in the book Finding the Right Hills to Die On. His system involves three levels of doctrinal importance. Primary doctrines are essential to the gospel and to Christian fellowship. Secondary doctrines, while not essential to the gospel, do affect some levels of Chrisitan fellowship. Tertiary doctrines should not define Christian fellowship.

To illustrate second-rank doctrines, Ortlund deals with three specific areas of disagreement. The first is baptism. The second is miraculous gifts. The third is gender roles as understood in the debate between complementarians (who believe that God assigns specific leadership roles to men but not women) and egalitarians (who believe that true equality between the sexes requires opening all leadership roles to women).

Ortlund recognizes that both the complementarian and egalitarian labels apply to a range of positions and that not everyone under each label can be treated the same. Nevertheless, he notes that the differences between the two positions are so practical that the issue cannot be avoided and that no truly mediating position will be possible. A church either will or will not ordain women to the pastorate, for example. It will or will not disciple married couples to recognize male headship within the home (117). The necessity of these choices leads Ortlund to insist that the dispute between complementarianism and egalitarianism cannot be treated as a third-rank difference.

Furthermore, Ortlund sets this debate in a larger social context. The West in general, and America in particular, is backing away from any notion of natural and determinative masculinity and femininity. These and related categories, such as marriage, are hotly contested, and this secular debate adds urgency to the dispute between complementarians and egalitarians (117–118).

Then Ortlund notes that the debate over gender roles is often a debate over how one interprets and appropriates Scripture. This is where he might have said more, for egalitarians follow at least three hermeneutical roads in arriving at their conclusions. How they draw their conclusion is sometimes as important as the conclusion itself.

The first road recognizes full biblical authority but sees Paul’s teachings about the role of women as a particular local application of generalized principles. A parallel could be drawn with the way many complementarians view Paul’s teaching about head coverings in 1 Corinthians 11. Many or most see head coverings as a temporary and culturally-bound application rather than as a timeless requirement. Many who have traditionally defended women preachers have done so by following this road, including some fundamentalists (W. B. Riley and Oliver W. Van Osdel are examples).

The second road to egalitarianism utilizes some form of either trajectory (I. Howard Marshall) or redemptive-movement (William Webb) hermeneutic. These hermeneutical techniques pay lip service to biblical authority, but they insist that God’s final word must be discovered by following a line that goes beyond Scripture itself. This final position may even nullify or contradict specific biblical statements.

The third road to egalitarianism seeks to discredit some biblical teachings in favor of others. For example, Paul King Jewett in Man as Male and Female argued that Paul’s teaching in 1 Timothy 2 reflected his chauvinism as a rabbi while Galatians 3:28 defined the true relationship between the sexes. This approach to the text severely undermines or flatly denies biblical inerrancy and integrity.

These three roads to egalitarianism require very different responses. While Ortlund chooses not to recognize it as such (119), biblical inerrancy is a fundamental of the faith. To arrive at egalitarianism by the third road places one on the far side of the watershed that divides orthodoxy from heterodoxy. Biblical inerrancy is a first-level issue, and defenses of egalitarianism that attack the inerrancy and integrity of the Bible are genuinely heretical. They exclude Christian fellowship at every level.

Defenses of egalitarianism that take the second road are also seriously flawed. While the trajectory and redemptive-movement hermeneutics claim to take a high view of the Bible, they nevertheless treat the biblical text like a wax nose. Advocates of these approaches have not succeeded in erecting methodological barriers and limitations that can successfully correct abuses of their hermeneutical techniques. While the use of either trajectory or redemptive-movement hermeneutics may not place their advocates outside the faith, it should certainly limit the possible circles of fellowship inside the faith. Using Ortlund’s classifications, I see this as an upper-second-level matter.

The first road to egalitarianism does not wreak nearly the damage to biblical authority that the other two roads do. Complementarians and egalitarians can meaningfully debate the question of applicability without calling into question either the clarity or authority of the Bible. Some level of Christian fellowship does exist and some level of Christian commonality should be demonstrated between the two groups.

Nevertheless, as Ortlund adequately shows, the difference remains both important and unavoidable. For that reason, fellowship between complementarians and egalitarians is necessarily limited and even impossible at some levels. As with other important differences within the faith, believers who do not agree must either limit their message or limit their fellowship if they are to get along.

I once heard a prominent professor from Dallas Seminary explaining to a student that he was complementarian, but his church was egalitarian—and he was determined that the church would not know his position. That is an example of limiting one’s message. He might better have found a church where he could live and teach his full convictions. That would be limiting one’s fellowship.

The degree to which either one’s message or one’s fellowship must be limited depends on the seriousness of the disagreement. The gravity of the egalitarian error hinges partly on one’s reasons for holding the egalitarian position. These reasons may constitute a fundamental error that places one outside the faith; they may constitute a severe error within the faith that bars most levels of fellowship; they may constitute a serious but not deadly error that allows some levels of fellowship while restricting others.

Perhaps it would be useful to weigh Ortlund’s three test cases against each other. The milder forms of the egalitarian error are less serious than the Charismatic error in almost any form. They are probably more serious than an error over the subject or mode of baptism—as long as the gospel is not at stake. See my previous essays on those topics to be reminded of my reasons for weighing them as I do.

It is worth noting that some complementarians also hold errors that may be as serious as some egalitarian errors. When complementarianism is used to defend a brutalizing, dominating, and dehumanizing attitude toward women, it is egregiously wrong. No biblical teaching held in a biblical way will ever justify abusive behavior. Sometimes we need to learn to limit our fellowship to both sides.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Faith! ’Tis a Precious Grace

Benjamin Beddome (1717–1795)

Faith! ’tis a precious grace,

Where’er it is bestowed;

It boasts of a celestial birth,

And is the gift of God.

Jesus it owns a King,

An all-atoning Priest;

It claims no merits of its own,

But looks for all in Christ.

To him it leads the soul,

When filled with deep distress;

Flies to the fountain of his blood,

And trusts his righteousness.

Since ’tis thy work alone,

And that divinely free,

Come, Holy Spirit, and make known

The power of faith in me.

Episode 44: The Mind/Body Connection with Mark-Stuckey & Brett-Williams, Part 1

In today’s episode, we discuss the mind/body connection with Dr. Mark Stuckey, M.D. and Dr. Brett Williams. We talk about how Scripture teaches us to answer the question of “Who are We?”

“It was really from that perspective that I first began to wrestle with these ideas as to how is God made us and are there limitations on what we should do and what are the principles in Scripture that guide how we treat people and how we deal with people? And again, back to that core issue of who am I?” – Dr. Mark Stuckey

Dr. Richard Redding, Colleague

Central Seminary opened a ministry in Romania shortly after the collapse of communism. Early on, we assumed that all the people of Romania were Romanians. Consequenlty, we tried to establish a campus in an ethnic Hungarian community. We soon learned that Romanians were reluctant to attend what they perceived as a Hungarian school. Thanks to the welcoming spirit and hard labors of Pastor Beniamin Costea, we were able to relocate to Arad in western Romania. In that location we could draw both majority Romanians and minority Hungarians.

We also drew one student who was neither. Richard Redding was an American missionary working in Romania under the Baptist Bible Fellowship. He began attending our classes, and he graduated with our first class in 1994, receiving his MABS. Two years later he graduated again with his MDiv. When I arrived at Central Seminary in January of 1998, the seminary was flying four men from Romania to Minneapolis to work on their DMin degrees. The goal was for these men to become the future backbone of a Romanian seminary. Richard was one of them, and he eventually graduated with his doctorate.

Richard and his wife Linda had been sent to Romania as part of the first wave of missionary activity after communism. They were already veteran missionaries from Colombia, and their skill in Spanish made it easier to learn Romanian. When they arrived in Romania, they found already-existing Baptist churches in nearly every major center. These were churches that had weathered the assaults of communist atheism and dictatorship. The churches were deep in piety but shallow in their understanding of the Bible and of Christian doctrine. As far as I know, Richard and Linda did not try to establish new Baptist churches. Instead, they gave themselves to strengthening the biblical understanding of existing Baptist pastors and to helping train up a new generation of ministry.

That is how Richard became the ideal go-between to help coordinate our Romanian and American administrations. He himself held a relatively minor post in the Romanian administration (I believe that he was the registrar). His true value lay in helping Americans and Romanians to understand each other’s mindsets and expectations. He and Linda also regularly hosted American professors when they came to teach in Romania.

In between class sessions, Richard also acted as an associate pastor to Beni Costea. This work included labors in two principal churches and several minor ones. Some American missionaries neither understood nor appreciated this arrangement—to them, it wasn’t really missions unless the Americans were the bosses. By working alongside Romanian pastors in their own churches, however, Richard managed to achieve a level of influence that far exceeded that of most American missionaries. He was able to play a significant role in bringing an entire contingent of Romanian pastors and churches to greater theological maturity.

Under communism, Romanian Baptists were very Arminian. They had little idea of how the Bible fit together or how the plan of God could be seen progressing across the biblical story line. They lacked skills in the biblical languages, and their understanding of Baptist distinctives had not been cultivated in decades. Central Seminary taught its students Greek and Hebrew. It introduced them to dispensationalism, and it got them thinking in terms of New Testament patterns for church order and cooperation.

Communism offered few benefits for biblical churches. One unintentional benefit was that, by blocking Western ideas, the communist government actually prevented liberal theologies from infecting Baptist churches. These theologies were only beginning to develop in Romania during the 1990s and early 2000s. The result was that the Baptist churches found themselves in the position that American churches had been in during the 1920s and 1930s.

Central Seminary tried to provide our students principles for dealing with this situation, and we saw some evidence of success. For example, at one point the government offered to begin paying Baptist pastors generously from state funds. To do this, however, Baptists would have to submit to a more centralized and controlled structure. Faced with this temptation, our graduates understood what was at stake. They opposed the offer and led Baptists to reject what would surely have become a poisoned chalice.

During those years, Richard Redding kept up quiet leadership from behind the scenes. As far as I can tell, he and Linda never attracted much attention to themselves, but their influence was evident. Romanian Baptists in their orbit were eventually able to plant churches in Austria, Italy, France, England, and even in the United States. Central Seminary graduates from those years have served churches in all those countries.

Richard and Linda left Romania for Mexico around 2010—maybe a bit earlier. By the time they moved, Richard had helped Central Seminary to educate nearly twenty percent of all the Baptist pastors in Romania. In about 2012 or 2013, financial considerations led Central Seminary to cease operations in Romania. By that time, however, Romanian pastors such as Gelu Pacurar and Marius Birgean had earned research doctorates. They had the knowledge and credentials to provide leadership so that seminary education could continue among Romanian Baptists.

In Mexico, Richard continued in educational ministry. He also found time to publish five science-fiction novels (the “Light-Plus” series) that can be found on Amazon. Incidentally, Richard claimed at least indirect responsibility for the fact that the Antichrist is depicted as Romanian in the Left Behind series.

After he began to develop physical difficulties, Richard and Linda retired from the mission field, eventually settling near Chattanooga, Tennessee. Then came a period of illness and decline. Finally, Richard was taken home to glory on New Years Eve.

Dr. Richard Redding was one of the best men I knew. He was a man of devotion, integrity, intelligence, warmth, hospitality, and humility. During the time that I saw him in action, he never occupied the driver’s seat. Yet he took responsibility for the smooth running of the vehicle, and his quiet influence helped to decide the direction it went. His work was never widely and publicly celebrated, but it deserves to be, and it will be someday. For now, we at Central Seminary acknowledge both our indebtedness and affection toward him.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Ye Faithful Souls, Who Jesus Know

Charles Wesley (1707–1788)

Ye faithful souls, who Jesus know,

If risen indeed with Him ye are,

Superior to the joys below,

His resurrection’s power declare.

Your faith by holy tempers prove,

By actions show your sins forgiven,

And seek the glorious things above,

And follow Christ your Head to Heaven.

There your exalted Savior see

Seated at God’s right hand again,

In all His Father’s majesty,

In everlasting pomp to reign:

Your real life, with Christ concealed,

Deep in the Father’s bosom lies;

And, glorious as your Head revealed,

Ye soon shall meet Him in the skies.

To Him continually aspire,

Contending for your native place,

And emulate the angel choir,

And only live to love and praise.

Word of the Father, Now in Flesh Appearing

[This essay was originally published on December 21, 2007.]

If Jesus Christ were not truly and perfectly God, He could not be our mediator. If Jesus Christ were not truly and perfectly human, He could not be our mediator. This much, Scripture makes clear.

Our problem is that we have absolutely no experience with divine‐human beings other than Jesus Christ. He is absolutely unique, the only one of His kind. For that reason, Christians have struggled to find words to express just who Jesus is.

With the Athanasian Creed we affirm that, as to their deity, the Father and Son are equally glorious, eternal, uncreated, incomprehensible, and almighty. Yet they are not two Gods, but one. So we confess.

Nevertheless, we also confess that we do not comprehend what we affirm. While the relationship of the Father to the Son involves no logical contradiction, it is inexplicable and impenetrable to the human mind. It rises above reason. We do not understand how such a thing can be.

Already bewildered, we then encounter the full humanity of the Son. Here we discover a person who, as to His deity, is coequal, coeternal, and consubstantial with God the Father, but who, without ceasing to be fully God, also becomes fully human. We are asked to believe that a person who is equal with God is also one of us.

Not everyone agrees. Often, people reject what they cannot explain. Worse yet, they modify the truth to fit some human explanation. So they have done with the person of Christ.

Some have denied His full deity. Ebionites saw Jesus as a good man, a teacher and prophet who kept the law. Arians explained Jesus as God’s first creation, so highly exalted above others that He could be called “a god,” but who was still not properly “God.” Adoptionists (Dynamic Monarchians) understood Jesus as a human who was elevated to divine status by some act of God.

Some have denied the distinction of the Son from the Father. The Sabellians (Modalistic Monarchians) affirmed that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit were simply three modes in which God presented Himself and not actual personal distinctions. As the same man might appear as husband to his wife, as teacher to his students, and as peer to his fellows, God presented Himself at one time as Father, at another as Son, and at another as Holy Spirit. Ultimately, however, the Trinity is a mask, and God is one and only one person.

Others have denied Jesus’ complete humanity. Docetists believed that the human body of Jesus was a mere phantom projected by the divine Christ. Apollinarians taught that Jesus possessed a human body and soul, but that the place of the rational, human spirit was taken by the divine Logos (in other words, Christ was 3/3 divine but only 2/3 human). Eutychians affirmed complete divine and human natures but saw the human nature as so recessive as to be almost completely overwhelmed by the divine—rather like a drop of honey in an ocean of water.

Still others have rejected the integrity of the person of Jesus Christ. Cerinthians believed that the divine Christ descended upon the human Jesus, only to abandon Him before the cross. Nestorians affirmed the full deity and full humanity of Christ but divided these two natures into two distinct persons, joined rather like Siamese twins.

The equal and opposite reaction was for others to affirm the unity of the person by denying the distinctiveness of the natures. Monophysites collapsed the divinity and humanity of Christ into a single nature. In principle this nature was supposed to be both divine and human, but in practice the divine so overwhelmed the human that Monophysitism became a reaffirmation of Eutychianism. A more subtle form of denying the distinction between the natures is Monothelitism, which denies that Jesus had a human will. De facto, this is a denial of the completeness of the human nature of Jesus.

These are not merely ancient heresies. They have had a tendency to reappear throughout church history. The Jehovah’s Witnesses are unreconstructed Arians. Mormonism applies Adoptionist principles not only to Christ but to all humanity. Many liberals have regarded Jesus simply as a human teacher or prophet, and contemporary biblical scholarship is witnessing a resurgence of interest in Gnostic understandings of Christ. Modalistic Monarchianism shows up in the teachings both of Witness Lee and of the so‐called “Jesus Only Movement,” represented by the United Pentecostal Church. The Coptic Orthodox Church still defends Monophysitism and condemns the Council of Chalcedon as “divisive.”

Our understanding of the person of Christ has been hammered out in opposition to these heresies. Each new heretical theory forced Christians to return to the Scriptures in order to test the theory against the text. At each new controversy, Christians erected a new barrier against heresy. They were forced to say, “Scripture teaches this but not that. We may say it this way but not that way.” This process resulted in the adoption of several public summary statements, each of which was more specific than the one that preceded it.

At the end of the day, here is what we must affirm. If Jesus Christ were not true God, He could not be our savior. If Jesus Christ were not true human, He could not be our savior. If Jesus Christ were not one person, He could not be our savior. If the person of Christ were divided, then He could not be our savior. If the natures were combined or transmuted, then He could not be our savior. All of this is summarized and elaborated in the formula of Chalcedon.

Nothing is more important to Christianity than the incarnation of Jesus Christ. A false step here can lead us to deny the gospel and plunge us into apostasy. We learn about the old heresies so that we may confront the new ones. We confront the new ones so that we may keep the gospel pure. We aim for precision in our understanding of Jesus Christ so that we may trust Him and worship Him as He is, rather than worshipping a false Jesus whom we have manufactured in our own idolatrous hearts.

In one sense, we are indebted to the heretics. Everything that we need to know about Jesus Christ is in the text of Scripture. If we had not been challenged by the heretics, however, we never would have studied the Scriptures as they deserved to be studied. We never would have noticed the depth and texture and richness of the biblical teaching concerning the incarnation. The heretics have forced us to discover exactly what Scripture says and what it forbids us to say.

We cannot explain the incarnation. We cannot fully comprehend the notion of a theanthropic person. But we can learn to be precise in saying who He is and who He is not. We can know Him. We can trust Him. We can love Him. We can worship Him. Word of the Father, now in flesh appearing: O come, let us adore Him, Christ the Lord.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Hark! A Thrilling Voice Is Sounding

Edward Caswall (1814–1878)

Hark! a thrilling voice is sounding:

“Christ is nigh,” it seems to say:

“Cast away the works of darkness,

O ye children of the day!”

Startled at the solemn warning,

Let the earth-bound soul arise;

Christ, our Sun, all sloth dispelling,

Shines upon the morning skies.

Lo, the Lamb, so long expected,

Comes with pardon down from heaven;

Let us haste, with tears of sorrow,

One and all, to be forgiven.

So, when next He comes in glory,

And the world is wrapped in fear,

May He then as our Defender

On the clouds of heaven appear.

Honor, glory, might and blessing

To the Father and the Son,

With the Ever-living Spirit

One in Three, and Three in One.

Erecting the Right Fences in the Right Places, Part Nine: Continuationism As a Secondary Doctrine

The book Finding the Right Hills to Die On is Gavin Ortlund’s theory of doctrinal triage. According to his theory, primary doctrines are essential to the gospel and to Christian fellowship. Secondary doctrines are not essential to the gospel, but they are necessary to some levels of Christian fellowship. Differences over tertiary doctrines should not inhibit Christian fellowship.

Ortlund illustrates his category of second-rank doctrines by applying it to three specific controversies. His second controversy is the one over the continuation of what he labels “spiritual gifts.” He does not address spiritual gifts in general, however, but specifically miraculous and revelatory gifts.

At the outset, Ortlund identifies himself as a continuationist “in both practice and conviction” (108). He also tries to limit his discussion to Reformed attitudes toward continuationism. Given the widespread influence of charismatics across the contemporary theological spectrum (including not only gospel-believing groups like Reformed or Wesleyan evangelicals but also ecumenical liberals, Romanists, and even Mormons), he has defined his discussion too narrowly. Since gospel deniers regularly practice charismatic gifts, supposed appearances of those gifts cannot possibly be taken as self-authenticating evidence for God’s activity or approval.

Admittedly, a comparatively mild version of continuationism is voiced within certain evangelical circles. It is represented by figures such as Wayne Grudem, John Piper, and Sam Storms. I assume that Ortlund holds this version of the theory. These figures and their followers, however, represent only a small fraction of charismatic continuationism. Adherents to the prosperity gospel far outnumber them (especially worldwide), as do devotees of the New Apostolic Reformation. The Grudem-Piper-Storms (and Ortlund?) version of continuationism barely amounts to a pebble in the mountain range of these larger movements.

The prosperity gospel is not the biblical gospel. It is a gospel of a different kind, and it falls under the anathema of Galatians 1:6–8. Furthermore, anyone claiming to be an apostle today is necessarily a false apostle (Acts 1:21–22; 1 Cor 9:1; 15:8), and Paul denounced false apostles as ministers of Satan (2 Cor 11:13–15). In other words, at least some of the time continuationism is a first-level, fundamental error. I acknowledge no Christian commonality with (for example) a Benny Hinn or a Kenneth Copeland. If Ortlund thinks that he can, then worse and worse.

If, on the other hand, Ortlund is willing to acknowledge how serious the errors of a Hinn or a Copeland are, then he needs to bring considerably more nuance into his discussion of Reformed continuationism. But he does not. He rests his argument fundamentally upon the fact that he can find Reformed progenitors who acknowledged some element of continuation for miraculous or perhaps even revelatory gifts. He relies especially heavily upon figures of the Reformation and the Puritan movement.

The problem with this appeal is that both the Reformation and the Puritans came prior to the defining point for the doctrine of miraculous gifts. One can find loose expressions of Christology among orthodox Christians before Nicea. One can find loose expressions of soteriology by evangelical Christians before the Reformation. But what Arius was to Christology, and what Johann Tetzel was to soteriology, early Pentecostalism was to miraculous gifts. It was Pentecostalism (and its forebears Edward Irving and John Dowie) that forced the issue on miraculous and revelatory gifts. These influences brought Christian thought to a defining point over these doctrines. We presently find ourselves standing at much the point that Athanasius stood with respect to Arius or that Luther stood with respect to Leo X. We cessationists are no more deterred than Athanasius was when he was informed that the whole world was against him.

I am not suggesting that continuationism is always a fundamental error, but beyond question it sometimes is. Even when it is not, the implications of charismatic theology reach far beyond a simple misunderstanding about the role of the Holy Spirit. For example, older Pentecostals and charismatics grounded their doctrine of present-day divine healing in the atonement, seriously distorting the biblical doctrine of the atonement and badly misreading Scripture. Third-wave charismatics presently ground their doctrine of healing in an over-inaugurated understanding of the kingdom leading to “power encounters.” (Incidentally, most cessationists affirm that God is able to heal miraculously; what they deny is that He has given the gifts of healing to individuals to exercise with the kind of discretion that Christians witnessed during the apostolic age.)

Similarly, the doctrine of revelation must be taken seriously. In the Old Testament, a prophet was to be tested partly by his ability to produce miraculous signs that were unmistakable and verifiable. A single false prophecy earned him the death penalty (Deut 18:18–22). Grudem has tried to soften this understanding of prophecy for the New Testament, but two responses must be noted. First, even most Third-wave charismatics disagree with him, insisting that church prophecy today is just as authoritative as Scripture for those to whom it is delivered (see, for example, the Fuller Seminary doctoral dissertation on this topic by Stephen Oldham). Furthermore, contra Grudem, 1 Corinthians 14:29 and 1 Thessalonians 5:19–21 do not show New Testament prophecy being sifted and weighed, 1 Corinthians 14:30–31 does not show prophecy being ignored, Acts 21:4 does not show prophecy being disobeyed—indeed, it does not relate a prophecy at all—and Acts 21:10–11 does not show prophecy being mistaken.

It is impossible in a short space to review every argument, but it should be clear that the charismatic error does not just involve misinterpreting a verse or two. In all its forms it represents a gigantic shift that rearranges much of the biblical system of faith and practice. It also relocates the methodological basis of evangelical theology from sola scriptura to ambo scriptura et experientia.

Ortlund wants to place continuationism in between the second-level and third-level on the scale of doctrinal importance. I insist that various charismatic errors are often first-level, fundamental errors, and they are never less than upper-second-level (using his taxonomy). I do not deny that some level of Christian fellowship remains possible with the more balanced Pentecostals and charismatics, but I do believe that whatever levels of fellowship are possible will be those that require a bare minimum degree of doctrinal agreement.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

As With Gladness Men of Old

William Dix (1837–1898)

As with gladness men of old

did the guiding star behold;

as with joy they hailed its light,

leading onward, beaming bright;

so, most gracious God, may we

evermore be led to Thee.

As with joyful steps they sped

to that lowly cradle-bed,

there to bend the knee before

Him whom heav’n and earth adore;

so may we with willing feet

ever seek Thy mercy-seat.

As they offered gifts most rare

at that cradle rude and bare;

so may we with holy joy,

pure, and free from sin’s alloy,

all our costliest treasures bring,

Christ, to Thee, our heav’nly King.

Holy Jesus, every day

keep us in the narrow way;

and, when earthly things are past,

bring our ransomed lives at last

where they need no star to guide,

where no clouds Thy glory hide.

In that heav’nly country bright

need they no created light;

Thou its Light, its Joy, its Crown,

Thou its Sun which goes not down;

there for ever may we sing

alleluias to our King.

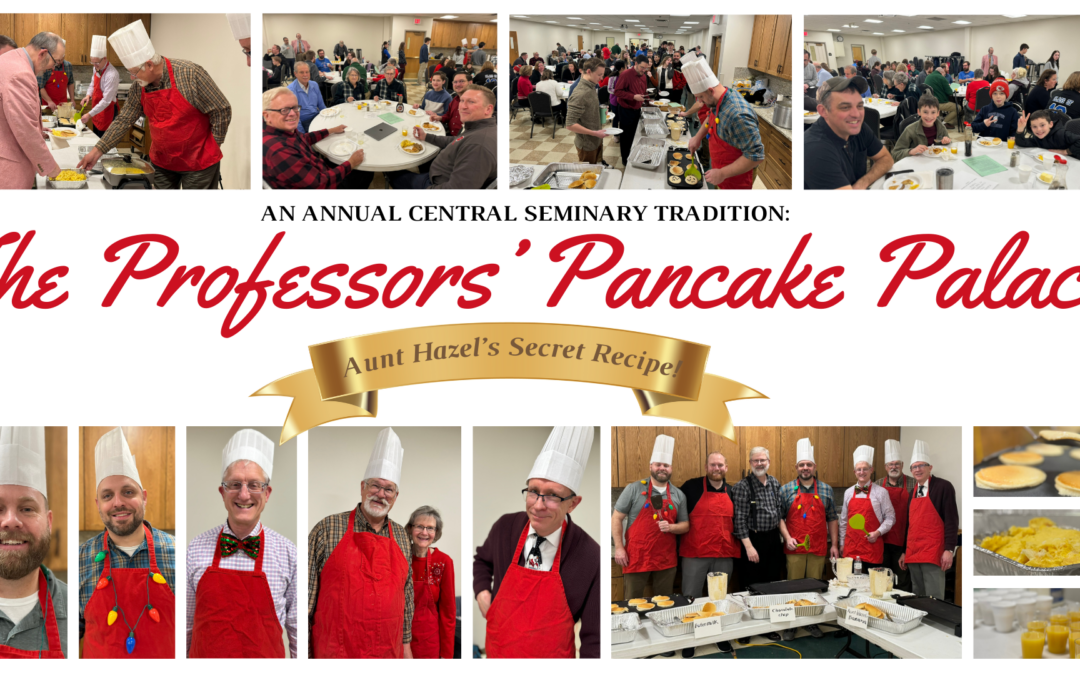

Professors’ Pancake Palace

As we near the finish line of our fall semester, we host our annual Professors’ Pancake Palace (pictures above from today’s festivities). This beloved tradition dates back to the days of Dr. Larry Pettegrew and his Aunt Hazel’s Secret Pancake Recipe. We have had countless wonderful moments sharing flapjacks and fellowship over the years. We’re already making plans again for next year. We hope you’ll join us! Apply today!

More pictures over on our Facebook page.

Erecting the Right Fences in the Right Places, Part Eight: Baptism as a Secondary Doctrine

In Finding the Right Hills to Die On, Gavin Ortlund develops a theory of doctrinal triage. In this theory, second-rank doctrines are not fundamental to the gospel, but they are important to some level of Christian fellowship. To illustrate how second-rank doctrines work, Ortlund addresses three areas of doctrinal controversy. The first one is baptism, a topic over which Christians widely disagree.

His discussion contains much that is helpful. Ortlund rightly notes that differences over baptism cannot be reduced to one simple issue. Instead, baptism involves a bundle of questions that get addressed differently by various Christians. Different answers to these questions result in whole varieties of positions on baptism.

Ortlund also argues that, in spite of these differences, baptism is important, and the questions cannot be avoided. He is right. Either churches will baptize or they won’t. If they do, they will either baptize infants or they won’t. They will either restrict baptism to immersion or they won’t. Believers who have committed themselves to definite views on baptism cannot usually settle contentedly in churches that deny those views.

According to Ortlund, baptism is obligatory for Christians. To use his language, being baptized is a matter of obedience to Christ. It plays an important role in the church’s life as a people of God. Baptism is a sign and seal of the gospel itself (103–104). Depending upon what Ortlund means by baptism being a “seal,” I find myself agreeing with most of what he says here (though I disagree with his remark that baptism symbolizes the washing away of sins). Baptism is sufficiently important that it does affect some levels of Christian fellowship. Specifically, it must not be ignored for church membership.

I also partially agree with Ortlund that baptism is not a doctrine on which the gospel is won or lost (104). He is right insofar as salvation does not depend upon getting baptized. As in the case of Cornelius (Acts 10–11), the New Testament clearly presents salvation coming before baptism.

And yet, sometimes the gospel can be and is lost over the matter of baptism. Ortlund notes in passing that some groups, claiming to be Christian, make baptism a necessary or even sufficient condition of salvation. Still, he never draws out the implications of this observation, preferring to limit his discussion mainly to Reformed understandings of baptism.

Nevertheless, the matter cannot be overlooked. In Roman Catholicism, baptism works ex opera operato (we might say automatically) to wash away the guilt of original and personal sins, to confer the grace of justification, and to place an indelible mark upon the soul. This form of baptismal regeneration constitutes a clear denial that justification is applied through faith alone. Thus, the Catholic understanding of baptism denies the gospel.

In Stone-Campbell (Church of Christ) soteriology, salvation is not applied until an individual is baptized. A professor in a Stone-Campbell college once explained to me that if someone trusted Christ for salvation but died in a car crash on the way to baptism, then that person would go straight to hell. While some Campbellites may have softened this view, it remains near the heart of Stone-Campbell preaching. It, too, constitutes a denial of the gospel.

In other words, sometimes errors about baptism are first-level, fundamental errors. They place the people who hold them outside the circle of gospel fellowship. Bible believers should not extend any level of Christian fellowship to advocates of Roman Catholic or Stone-Campbell soteriology.

Ortlund also lists Lutherans among those who affirm baptismal regeneration, but he fails to note that their situation is different. Conservative Lutherans (such as Missouri Synod Lutherans) believe that salvation is applied through faith alone, but they also affirm that baptized infants are justified. How can they have it both ways? The answer is that they see infants as capable of faith. This faith is dormant in that the infant is not aware of it (like our faith while we are asleep), but it is nonetheless real. This dormant faith can be created in the infant through baptism.

In other words, the Lutheran view does not teach that baptism is either a necessary or a sufficient means of salvation. Granted, it is an odd view. Menno Simons is supposed to have wryly asked a Lutheran how many people the apostles baptized in their sleep. Furthermore, the Lutheran view sometimes communicates false assurance to those who were baptized as infants. In spite of these problems, this view does not deny that justification is applied through faith alone. While I judge that this Lutheran view is badly in error, it is consistent with the bare message of the gospel. Consequently, some level of Christian fellowship is possible with such Lutherans. I personally cherish the warmth of Christian friendship with professors at the Free Lutheran seminary across Medicine Lake from the Baptist seminary where I teach.

In the Reformed view, baptism identifies an individual with the believing community. It is administered to the infant children of church members, not because they are thought to be saved but because they are seen as part of the community. While this view confuses Old Testament Israel with the New Testament Church, it is miles away from denying anything that is essential to the gospel. I could not join a church with members who held this view, but I am willing joyfully to extend multiple other levels of fellowship to them.

In sum, the crucial issue with baptism is not so much its subjects or mode (though those questions do matter) as its meaning. Baptism can be understood in some ways that deny the gospel. These denials elevate some errors about baptism to the level of fundamental, first-rank errors. They break all Christian fellowship.

Other errors are of a lesser nature, limiting Christian fellowship at some levels but not others. As with all differences over non-fundamental doctrines, the question here is not whether Christian fellowship is possible. The question is which levels of fellowship are affected by the differences. Where the gospel is not at stake, doctrinal disagreement rarely makes fellowship an all-or-nothing proposition.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

The Lord Is Come

Isaac Watts (1674–1748)

The Lord is come; the Heav’ns proclaim

His birth; the nations learn His Name;

An unknown star directs the road

Of eastern sages to their God.

All ye bright Armies of the Skies,

Go, worship where the Saviour lies;

Angels and Kings before Him bow,

Those gods on high, and gods below.

Let idols totter to the ground,