Theology Central

Theology Central exists as a place of conversation and information for faculty and friends of Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Posts include seminary news, information, and opinion pieces about ministry, theology, and scholarship.

Most Interesting Reading of 2024: Part One

It’s that time of year again. Other authors issue bibliographies of “best books” they’ve read. I put out a listing of reading that I personally found most interesting. This year, it happens that “interesting” also broadly corresponds to “good,” though in some years, books can be interesting exactly because they are bad. But I promise, all the following are good, though in different ways. You may or may not find them interesting, but I did, and that’s why they’re here.

Adler, Mortimer J. Six Great Ideas. New York: Touchstone, 1981. 256pp.

The six ideas are divided into two sets. Truth, goodness, and beauty are ideas we judge by. Liberty, equality, and justice are ideas we act on. Adler compares and contrasts approaches to these ideas, helping his readers understand the issues surrounding them. Adler invariably stimulates his readers’ thinking. He is one of those authors who deserves his own shelf in your library.

Anderson, Ryan T. Truth Overruled: The Future of Marriage and Religious Freedom. Washington: Regnery, 2015. 256pp.

Famous for authoring a conservative work that was banned by Amazon, Anderson is one of the most articulate conservative voices addressing gender issues today. In Truth Overruled he argues from natural law that the definition of marriage cannot be stretched to include two people of the same sex. The argument is both sound and accessible to readers with, say, a high-school education.

Blomberg, Craig L. Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey. 3rd ed. Nashville: B&H, 2022. 720pp.

As Blomberg’s subtitle implies, this work has two goals. One is to survey the contents of the four gospels, but the more important is to deal with introductory issues. These include the various issues related to the Jesus of History and the Christ of Faith. Blomberg provides a good, accessible overview of the questions, combined with a competent, conservative response. Parts of the work are idiosyncratic, but this is overall a very helpful book.

Butterfield, Rosaria. The Gospel Comes with a House Key: Practicing Radically Ordinary Hospitality in Our Post-Christian World. Wheaton: Crossway, 2018. 240pp.

Any book by Butterfield is worth reading. Her early books present a biblical perspective on homosexuality and lesbianism. This book deals more specifically with hospitality as a Christian duty. Butterfield talks about the what, the how, and the why. The result is that she sets a standard for hospitality that many readers will despair of ever being able to meet. Even so, the challenge is good and necessary.

Dubal, David. The Essential Canon of Classical Music. New York: North Point, 2003. 800pp.

I loved classical music from the first time I heard Tchaikovsky’s Overture Solonnelle, but only during seminary did I become a serious listener. I found that the field is so large as to bewilder an outsider. Eventually you start to find out what you like, and you look for more of it. Dubal’s work is useful for middle-level listeners who have got their feet on the ground but who wonder where to go next. Dubal surveys the entire field by period and composer. He also includes a recommended discography.

Flew, Antony. There Is A God: How the World’s Most Notorious Atheist Changed His Mind. New York: HarperOne, 2009. 258pp.

When I was being educated, the New Atheists had not yet captured public interest. During those years, Antony Flew was recognized as the ablest academic proponent of atheism. In this book, Flew tells how he became an atheist and why he eventually abandoned atheism for theism. The book includes Flew’s criticism of the New Atheism. It also includes a dialogue about Jesus with N. T. Wright. One could wish that it included a clear profession of faith in Christ.

Frahm, Eckhart. Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Empire. New York: Basic, 2023. 528pp.

The Assyrian Empire intersects the history of divided Israel and Judah in dramatic ways. Ultimately, the Assyrians were responsible for the dismantling and captivity of the northern kingdom. Frahm, an Assyriologist who teaches at Yale, offers in this work an overview of Assyrian history. While he is sometimes critical of the biblical chronology, Frahm does much to explain the pressures that the kings of Israel and Judah (not to mention other nations) faced from Assyrian expansionism. He has good theories about how Assyria rose to power and why it fell.

Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Naziism, and the Politics of Identity. New York: NYU, 2003. 271pp.

One of my study projects involves a version of white supremacy known as Identity Christianity. Eventually, I hope to do some writing on the subject. Identity Christianity is a quasi-Christian movement, generally cultish (though some versions of it are Trinitarian), with its own theology. Not many people will find this kind of reading interesting, but it helped me fit together some of the players and ideas in the Identity Christian movement.

Grossman, Miriam. Lost in Trans Nation: A Child Psychiatrist’s Guide Out of the Madness. New York: Skyhorse, 2018. 360pp.

This book is a deep dive into the influence that the Trans movement has exerted over the mental health profession. Grossman writes as an insider, a child psychiatrist who has dealt with gender issues for years. She is clearly outraged, however, by the current Trans ideology, which she believes is deeply harmful to children. She includes an account of how that movement uses professional and legal pressures to get doctors and parents to conform, and she also provides helpful strategies for dealing with authorities and children when those children announce that they are Trans. The discussion is long, and sometimes it is tedious, but every pastor should read this book.

This list is only the beginning. I’m working alphabetically and we are only through the letter G. Yes, there’s more to come! Next week I’ll be back with more of my “most interesting reading” of 2024.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Let Those Who Doubt the Heavenly Source

John Bowring (1792–1872)*

Let those who doubt the heavenly source

Of revelation’s page divine,

Use as their weapons fraud and force—

No such unhallowed arms are mine.

I only wield its holy word—

Reason its shield, and truth its sword.

I doubt not—my religion stands

A beacon on the eternal rock—

Let malice throw her fiery brands;

Its sacred fane has stood the shock

Of ages—and shall tower sublime

Above the waves and winds of time.

Infinite wisdom formed the plan;

Infinite power supports the pile;

Infinite goodness poured on man

Its radiant light—its cheering smile.

Need they thy aid? Poor worm! Thy aid?

O mad presumption—vain parade!

Thou wilt not trust th’Almighty One

With His own thunders—thou wouldst throw

The bolts of Heaven! O senseless son

Of dust and darkness! Spider! Go,

And with thy cobweb bind the tide,

And the swift, dazzling comet guide.

Yes! Force has conquering reasons given,

And chains and tortures argue well—

And thou hast proved thy faith from Heaven,

By weapons thou hast brought from hell.

Yes! Thou hast made thy title good,

For thou hast signed the deed with blood.

Daring impostor! Sure that God

Whose advocate thou feign’st to be,

Will smite thee with that awful rod

Which thou wouldst seize—and pour on thee

The vial of that wrath, which thou

Wouldst empty on thy brother’s brow.

* [Editor’s note: This poem is a striking condemnation of the use of force as a means of spiritual persuasion, which Baptists also disdain. The author, though, is a Unitarian. His best-known text, still sung in many Trinitarian churches, is In the Cross of Christ I Glory.]

Most Important News of 2024

[This essay was originally published on January 3, 2013. The editor has taken the liberty of updating the year; the essay is otherwise unaltered.]

Many periodicals make a New Year’s tradition of summarizing the most important stories of the past year. That tradition has never been followed by In the Nick of Time, but I thought this year might be a good time to begin. Since I’d never done this before, I perused several lists that others had put together. What struck me is that they universally missed the most important stories. So, in no particular order, here are my picks for the top stories of 2024.

Jesus Did Not Return

Few if any news outlets have reported that the Rapture did not occur during 2024. We believers are still on earth. We were unexpectedly granted an entire extra year to prepare ourselves. We were given a whole twelve months for devotion to our Lord. We had fifty-two whole weeks to apportion our time, energy, and money in such a way that as many people as possible (including ourselves) would be ready for His coming. The non-Rapture of the church during 2024 is clear evidence that the Lord is longsuffering to us-ward, not willing that any should perish, but that all should come to repentance. Eager as we are to be with Him in heaven, we can rejoice that He intends to show mercy to yet more sinners.

Few Were Disappointed

Almost as remarkable as the non-Rapture is the non-disappointment of the saints. Those who obeyed Scripture were looking for the blessed hope and glorious appearing of the great God and our Saviour Jesus Christ. For such people, every year in which they have not yet glimpsed His face leaves them both heartsick for Him and homesick for a better country, that is: an heavenly. They yearn for the city which hath foundations, whose builder and maker is God. They exhort one another, and so much the more, as they see the day approaching. The absence of this eagerness for the coming and presence of Jesus is certainly news.

Many Were At Ease

People who seek a better country are willing to dwell in tabernacles. They confess that they are strangers and pilgrims on the earth. On the other hand, those who are mindful of that country from whence they came out might have opportunity to return. For the former, God is not ashamed to be called their God. For the latter—well, they are newsworthy. It is as if, when they look up the word world in their thesaurus, they find the synonym friend. And because iniquity shall abound, the love of many shall wax cold. That is news.

The Government Martyred No One

Nowhere in the United States did any level of government—local, state, or federal—kill any Christian believers because of their testimonies. We have not yet resisted unto blood. On the contrary, we have been granted an opportunity to lift up the hands which hang down, and the feeble knees; and to make straight paths for our feet. We have been given another chance to follow that holiness without which no man shall see the Lord. If that’s not news, what is?

Christians Stood Up for Their Rights

It is no great thing that Christians, like Paul and Silas in Philippi, would challenge governments that fail to keep within their proper boundaries. What is newsworthy is that Christians should decide that the life of faith requires them to insist upon their rights instead of approving what is excellent. Only through the latter may a believer be sincere and without offense until the day of Jesus Christ. Here is the news: Christians have forgotten that one who strives for the mastery is temperate in all things. They are unaware that we become all things to all men, not by imitating them and seeking their approval, but by denying ourselves whatever rights and privileges would block us from serving them. That Christians should spend their efforts defending their rights would certainly be news to Paul: “But I have used none of these things: neither have I written these things, that it should be so done unto me: for it were better for me to die, than that any man should make my glorying void.”

God Was Denied Glory

The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament shows His handiwork. Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of those who bear God’s image spent the year exchanging the glory of the incorruptible God for an image made like to corruptible man, and to birds, and fourfooted beasts, and creeping things. They also spent the year bearing the consequences of uncleanness through the lusts of their own hearts, to dishonor their own bodies between themselves. Here is some news: God will not give His glory unto another. People are condemned first and foremost, not because they have broken God’s law, but because they have dishonored Him by preferring idols.

God Unleashed His Power

The gospel is the power of God unto salvation for everyone who believes. The gospel is not like a yapping Chihuahua that needs to be kept on a leash to protect it from the big dogs. The gospel is like a lion that pulls down its prey and subdues it. The gospel has the power to penetrate the hardest heart, humble the most arrogant mind, and bring the vilest sinner to repentance. News flash: the gospel never needs to be protected. It needs to be set loose. It did its work during 2024. The salvation of a single soul (and many were saved, all over the world) is a magnificent display of the infinite power of God.

Billions Are Still Lost

As 2024 closed, billions and billions of human beings, made in God’s image, were still lost and on their way to hell. Of these, the majority had never even heard the good news of salvation by grace alone through faith alone in the substitutionary death and bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ. Billions had never even heard the name of Jesus or seen a Bible. After two millennia, Christians have still not completed the task of going into all the world and preaching the gospel to every creature. They see a world wholly given to idolatry, and the news is that their spirit is not stirred in them. They do not dispute in the market daily with them that meet them. From these billions of unrepentant sinners, God is not receiving the glory and worship that He deserves—and He commands all men every where to repent. He has appointed a day in which He will judge the world in righteousness by that Man whom He has ordained. The news is that we still have a job to do.

* * *

The biggest news of 2024, and the biggest news of every year, is the gospel itself. The gospel is not a religious philosophy. It is not a collection of moral precepts. It is not a guide to self-improvement. It is not a stimulus for spiritual inspiration. It is news—news about events that occurred when God entered space and time, assumed a human nature, died to bear the penalty of human sin, and arose bodily from the dead. Not only is the gospel news, it is good news. It is the best news that sinful humans could ever hear.

Spread the news.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

The Day Is Past and Gone

John Leland (1754–1841)

The day is past and gone,

The evening shades appear.

O may we all remember well

The night of death draws near.

We lay our garments by,

Upon our beds to rest;

So death will soon disrobe us all

Of what we here possess.

Lord, keep us safe this night,

Secure from all our fears;

May angels guard us while we sleep,

Till morning light appears.

And when we early rise,

And view th’unwearied sun,

May we set out to win the prize,

And after glory run.

And when our days are past,

And we from time remove,

O may we in Thy bosom rest,

The bosom of Thy love.

The Man in the Shadows

During the Christmas season, two figures stand rightfully in the spotlight. One is Jesus, who was born in Bethlehem. The other is Mary His mother. A third figure generally remains somewhere in the shadows: he is known to have been present but hardly seems to matter. That man is Joseph.

Many Christians treat Joseph as a placeholder. Since they know that Jesus was conceived and born of a virgin, they assume that Joseph was present only as Mary’s husband. They take it as incidental and almost accidental that he was in the story at all. After all, what did Joseph contribute? He was a husband to Mary. He provided a male parental figure for Jesus. Perhaps he trained Jesus in the trade of construction. The story, however, would be substantially the same had Joseph never lived. Another man—or no man at all—might have done as well.

The Gospels challenge these assumptions about Joseph. They provide reasons for saying that he played a unique role in the nativity of our Lord. Without Joseph, the mission of Jesus Christ could never have succeeded. He was a remarkable man for several reasons.

At the least, Joseph is important because of his character. Matthew calls him a just or righteous man (Luke 1:19). Only about ten individuals in the Bible get called just or righteous. This designation already places Joseph among the elite.

His righteousness, however, was not of the priggish sort. It clearly included an element of compassion or mercy. Joseph was unwilling to subject Mary to shame, even before he knew that her pregnancy was caused by the Holy Spirit. Instead, he settled on a private divorce to end their marriage.

Joseph was more than Mary’s fiancé. He was legally her husband and she was legally his wife. Even though they had not yet consummated their marriage, and even though they were not yet living together, a divorce was necessary to dissolve their relationship. This was what Joseph planned to do, but he did not rush into it. Joseph must have been a temperate and deliberate man, because he was still pondering the situation when he dozed off and was confronted in a dream by an angel.

The angel assured Joseph that Mary was faithful to him. Her pregnancy was miraculous, something that was wrought by the Holy Spirit. The angel told Joseph to complete the marriage with Mary and to bring her into his home. This was a significant act, one that would be widely understood to mean that Joseph acknowledged the child. When Joseph took the final steps to complete his marriage with Mary, he was extending public acceptance to Jesus as his own offspring.

The angel gave further instructions about the child. He told Joseph, “You shall call his name Jesus,” a name that means savior or deliverer. The point is that Joseph was told to do the naming. Of course, this does not exclude Mary from being involved in the naming, but a child’s father had naming rights that could override the mother’s wishes (see the example of Zacharias, Elisabeth, and John in Luke 1:59–63). By exercising this right, Joseph was underlining his acceptance of the child Jesus as his own.

This point is critical: even though Jesus was not the biological descendant of Joseph, he was more than a stranger who was fostered in Joseph’s home. He was even more than adopted. From a legal point of view, Jesus was the son of Joseph, with all the rights, honors, and privileges pertaining thereto. And being the son of Joseph did come with rights, honors, and privileges.

Joseph stood in the direct line of descent from King David through King Solomon. By right of primogeniture, under the terms of the Davidic Covenant (2 Sam 7:12–16) Joseph held the title to the throne of David. He could not claim that title because of the curse placed on King Coniah (Jer 22:24, 30). By affirming Jesus as his legal son, however, Joseph passed the right of succession on to Jesus.

As the legal son of Joseph, Jesus headed the dynasty of Solomon. He held the title to occupy the throne of David. Because He was not Joseph’s biological son, however, He was not under the curse of Coniah. Since Mary was also a descendant of David through David’s son Nathan (Luke 3:23–31; 2 Sam 5:13–14), Jesus’ virgin birth fulfilled God’s promise that a descendant of David would rule Israel.

Was Joseph’s fatherhood of Jesus recognized? Luke indicates that Jesus was believed or thought to be the son of Joseph (Luke 3:23). Years later, he was still referred to as “the carpenter’s son” (Matt 13:55–57). He was called “the son of Joseph, whose father and mother we know (John 6:42). Indeed, Mary, talking to Jesus, could refer to Joseph as “your father” (Luke 2:48). The suggestion that the circumstances of Jesus’ birth might have temporarily slipped from Mary’s mind is simply ludicrous. More than once, Luke’s gospel names both Mary and Joseph together as Jesus’ parents (Luke 2:27, 41).

Joseph fulfilled the role of human father to Jesus. When Herod’s paranoia threatened the child, the angel warned Joseph to move the family to Egypt. When the threat had passed, the angel again appeared to Joseph, permitting him to take Mary and Jesus home to Nazareth. Then every year Joseph would take his family to Jerusalem for Passover (Luke 2:41). Since Jesus was increasing in favor with God and man (Luke 2:52), Joseph must have played a significant role in His spiritual upbringing.

The last glimpse we get of Joseph is when the twelve-year-old Jesus was disputing with the doctors in the temple. Probably Joseph was older than Mary, and he may have died shortly after that event. He was certainly gone before Jesus began His public ministry. The years during which Joseph parented Jesus were brief but crucial.

Much of Joseph’s life is hidden from us, but the little that we do know is vital. He was a just man, a good man, a devout man. His royal fathers can rightly be proud of him. He opened their dynasty to Mary’s son, the Savior. He gave the Savior a name, a title, a throne, and a home. Joseph is truly a hero of Christmas.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Beside Thy Manger Here I Stand

Paul Gerhardt (1607–1676); tr. William Martin Czamanske (1873–1964)

Beside Thy manger here I stand,

Dear Jesus, Lord and Savior,

A gift of love within my hand

To thank Thee for Thy favor.

O take my humble offering;

My heart, my soul, yea, everything

Is Thine to keep forever.

With joy I gaze upon Thy face;

Thy glory and Thy splendor

Are greater than my heart can praise,

And songs can fitly render.

O that my mind might truly be

As boundless as the deepest sea—

’Twould still be lost in wonder.

O grant me this abundant grace,

And let it be Thy pleasure

That I may be Thy dwelling place,

Dear Savior, sweetest treasure!

O let me be Thy manger bed,

Then shall I lift my lowly head

With joy beyond all measure.

Until the Lord Shouts

It is my sad duty to report that Caleb Counterman, a Doctor of Ministry student at Central Seminary, died suddenly on Sunday morning. He was driving his wife Jessica to church when his car hit a patch of ice. In the ensuing crash, Jessica’s life was preserved, but Caleb was thrown out of the car and into the arms of Jesus.

A graduate of Maranatha Baptist University, Caleb received his seminary training at Calvary Baptist Seminary in Lansdale, Pennsylvania. After years of pastoring, he enrolled in the D.Min. program at Central Seminary. He was a straight-ahead kind of guy. He knew what he thought and was convinced of what was right. He set clear goals for himself. He rarely deviated from these guiding lights.

While Caleb was a thinker, he was even more of a “doer.” He was a hard charger. His ministry could not be confined to a church building. He was active in his public school system, where he stood as a consistent Christian witness. He was elected to serve on the county board for Grundy County, Illinois. While working on his D.Min. at Central Seminary, he also completed a master’s degree in apologetics from another institution. These are not the actions of an idle man.

Guided by his principles, Caleb was a man to make difficult decisions and to lead in unpopular directions. Some years back, I attended a meeting of a national association of fundamentalist churches where he was present. Attendees were buzzing about a decision that the organization’s executive body had recently made. Many people opposed the decision, but nobody seemed willing to confront it. Even though it was his first meeting, Caleb stood up in the business session and moved that the decision be rescinded. After considerable debate, his motion was adopted. Some who opposed the motion saw Caleb as a troublemaker. I saw him as a man of conviction who had the courage to do what he (and I) thought was the right thing.

Most of what I saw of Caleb was either his public persona or his classroom presence. I knew him as a student who loved to explore and debate ideas. I do not recall, however, that I ever saw him in action as a pastor or a family man. Others are better suited to address those parts of his life, and I am sure that many will.

In addition to his wife Jessica, Caleb is survived by two sons, Levi and Jared. His two brothers, Luke and Simeon, are also pastors. His father and mother, Andrew and Jo Ellen, are also still active. Andrew, who is also a Central Seminary alumnus, serves as associate pastor alongside Simeon.

Caleb’s death is one of those events in which we are forced to recognize that a wise, benevolent, and gracious Providence may also be severe. Caleb would not have chosen the events of last Sunday morning. Neither would his wife, his sons, his brothers, or his parents. Yet these events surely fall under the purview of an infinitely wise, loving, and powerful God. Difficult as Caleb’s death is for his friends and loved ones, it was planned and permitted by a God who is both fully sovereign and infinitely good.

The truth is that sometimes God’s love allows us to be hurt—particularly since we still live in a world that endures the effects of sin. Our very mortality is the result of sin. Death is an intruder and an enemy, never a friend. Those who pass through the valley of the shadow of death (as Caleb’s loved ones are now doing) do really feel the bitter sting of that enemy. But even in that dark valley we remember that the sting of death has been pulled. Death will not be allowed the final or decisive word. Death’s victory is only a fading mirage. It has already been nullified by the resurrection of our Lord (1 Cor 15), who Himself passed through the gates of death and came forth again. Thus, those who are in the valley of the shadow of death need fear no evil. The God who permitted this calamity intends it all for good, and one day the weight of crushing sorrow will be transmuted into the exuberance of joy bursting into exultation. Every tear will be replaced with a far more exceeding weight of glory.

Meanwhile, we still sorrow, though not as those who have no hope. We recognize that God claims us as His own, and He uses us as He will. Sometimes He uses us up, as He did with Caleb last Sunday morning. Even so, He knows what He is doing, and insists that we must trust Him.

Caleb surely did trust himself to the Living God and to Christ Jesus the Lord. Here is something that he wrote a couple of years ago.

We need to emphasize what it means to find identity in Christ. He created us for a purpose. He loved and will always love us. We find our affirmation and value in Him. He will provide strength through this life as we follow Him. We can have victory over temptation because of His promised help and work. There is a promise of a glorified body and spirit because of Christ.

Caleb Counterman found his confidence and his identity in Christ. Because of Christ, because of Christ’s cross-work, and because of Christ’s resurrection, we also have confidence that all will be well. When the Lord returns, when He shouts that cry of command, then our sadness will forever end. For now, we cling to hope in the midst of our tears, but we hope with confidence, because Christ is our life. We shall hold fast to our confidence until the Lord shouts.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Courage in Death and Hope in Resurrection

Isaac Watts (1674–1748)

When God is nigh, my faith is strong,

His arm is my almighty prop:

Be glad my heart; rejoice my tongue,

My dying flesh shall rest in hope.

Though in the dust I lay my head,

Yet, gracious God, thou wilt not leave

My soul forever with the dead,

Nor lose thy children in the grave.

My flesh shall thy first call obey,

Shake off the dust, and rise on high;

Then shalt thou lead the wond’rous way

Up to thy throne above the sky.

There streams of endless pleasure flow;

And full discoveries of thy grace

(Which we but tasted here below)

Spread heav’nly joys through all the place.

About Pardon

News reports this week are buzzing with President Joe Biden’s pardon of his son, Hunter. Convicted on firearms and tax charges, the younger Biden was awaiting sentencing as his father neared the end of his presidential term. The president had insisted repeatedly that he would let justice run its course, and that he would not pardon his son. In spite of these assurances, President Biden announced that he was pardoning Hunter not only for the convictions over tax evasion and lying to a licensed firearms dealer, but also for any other federal crimes that he may have committed or taken part in from January 1, 2014, through December 1, 2024.

Interestingly, the termination hour of the pardon was still future at the time it was announced. The president may not have realized what he was doing, but he effectively granted his son impunity to commit any sort of federal crime over the next several hours. Whether Hunter took advantage of this permission is not known. What is known is that the pardon covered all crimes, actual or potential, acknowledged or unacknowledged, during the specified period.

Even some pundits on the Left have expressed perplexity over the pardon, and those on the Right have voiced outrage. One commentator even titled his report, “The Biden Crime Family Gets Away with It.” Some have attributed a cynical motive to the pardon: by protecting his son, President Biden puts a stop to any potential investigation that might explore his own wrongdoing.

We need not suggest such a sinister impetus to explain the president’s action. Normal paternal affection is a sufficient rationale. All other things being equal, what father would not wish to keep his child from spending years in prison? If we had the power, which of us would not be tempted by love to cancel our son’s penalties for wrongdoing, even if those penalties are deserved?

But all other things are not equal. Assuming the best of motivations for President Biden—love for his son—he still cannot rightly act without heeding other concerns. Chief among those is a concern for justice. The charges against Hunter Biden were not trumped up. His prosecution was not some form of vengeful lawfare. Hunter broke just laws, and those laws had just penalties attached to them.

Injustice disturbs moral balance. Moral balance can only be restored through judgment and retribution. Justice is not about rehabilitating wrongdoers, recompensing victims, reducing recidivism, or restraining crime. Those are good and useful things, but they are not justice. No, justice is about judgment and retribution. There is no justice without judgment, and there is no judgment without retribution.

Therein lies the problem with Hunter Biden’s pardon. In this case, parental mercy comes at the cost of public justice. No one seems to be suggesting that Hunter was wrongfully convicted. He himself pled guilty to three felony charges of tax evasion. To some extent, every taxpayer was harmed by his conduct. More seriously, he held a just law up to contempt. There were no mitigating circumstances. Consequently, the presidential pardon has thwarted justice.

The contest in this case is between love and justice. The president was caught on the horns of a dilemma: he could show love, or he could uphold justice, but he could not do both. What he chose to do was to seize one horn of the dilemma. He chose in favor of love. While we might sympathize with him, we cannot justify him. He has betrayed his office.

Justice does not allow judges the option of ignoring the law, and the point of law is to assign penalties to infractions. If this principle applies to human judges and other sworn to uphold the law—and it does—then how much more does it apply to the Judge of all? The Judge to whom we must all render account?

We know that we are lawbreakers. We have sinned and come short of the just requirements of God’s standard (Rom 3:23). Furthermore, God’s law attaches a penalty to our misdeeds: “the wages of sin is death” (Rom 6:23). Much as He loves us, God is not free simply to overlook our lawbreaking. If He failed to inflict the penalty, He would be untrue to His law, which would make Him untrue to Himself. He would not be God.

So how can God as Judge issue pardons to sinners? Indeed, how can He pronounce sinners righteous in His sight (which is what justification means)? Would not such a pardon and such a verdict be as inconsistent with justice as Hunter Biden’s pardon is?

No, it would not. The reason that God’s forgiveness does not violate justice is because the full penalty of the law was inflicted upon Christ on the cross. In the moment of His passion, Jesus became our substitute, took our place, and died our death. In other words, the full penalty of the law has already been paid, so that when we believe on Christ, God can rightly cancel our guilt.

There is no justice without judgment, and there is no judgment without retribution. The retribution for our sins—our lawbreaking—was laid on Jesus, and He paid it fully. He endured all that God’s just law demanded.

If we have believed upon Christ, then we, too, have been pardoned. In fact, we have received more than pardon. We have received a verdict of righteous for Jesus’ sake. God has charged our guilt against Jesus, and He credits Jesus’ righteousness to us.

God is infinitely just. God is also infinitely loving. In His wisdom, God found a way to be true both to His love and to His justice. He is “just, and the justifier of him which believeth on Jesus” (Rom 3:26).

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

A Pardoning God

Samuel Davies (1723–1761)

Great God of wonders, all thy ways,

Are matchless, Godlike, and divine;

But thy fair glories of thy grace,

More Godlike and unrival’d shine,

Who is a pardoning God like thee?

Or who has grace so rich and free?

Crimes of such horror to forgive,

Such guilty daring worms to spare,

This is thy grand prerogative,

And none shall in the honour share.

Who is a pardoning God like thee?

Or who has grace so rich and free?

Angels and men, resign your claim,

To pity, mercy, love, and grace;

These glories crown Jehovah’s name,

With an incomparable blaze.

Who is a pardoning God like thee?

Or who has grace so rich and free?

In wonder lost with trembling joy,

We take the pardon of our God,

Pardon for crimes of deepest dye,

A pardon bought with Jesus’ blood.

Who is a pardoning God like thee?

Or who has grace so rich and free?

O may this strange, this matchless grace,

This Godlike miracle of love,

Fill the wide earth with grateful praise,

And all the Angelic Hosts above,

Who is a pardoning God like thee?

Or who has grace so rich and free?

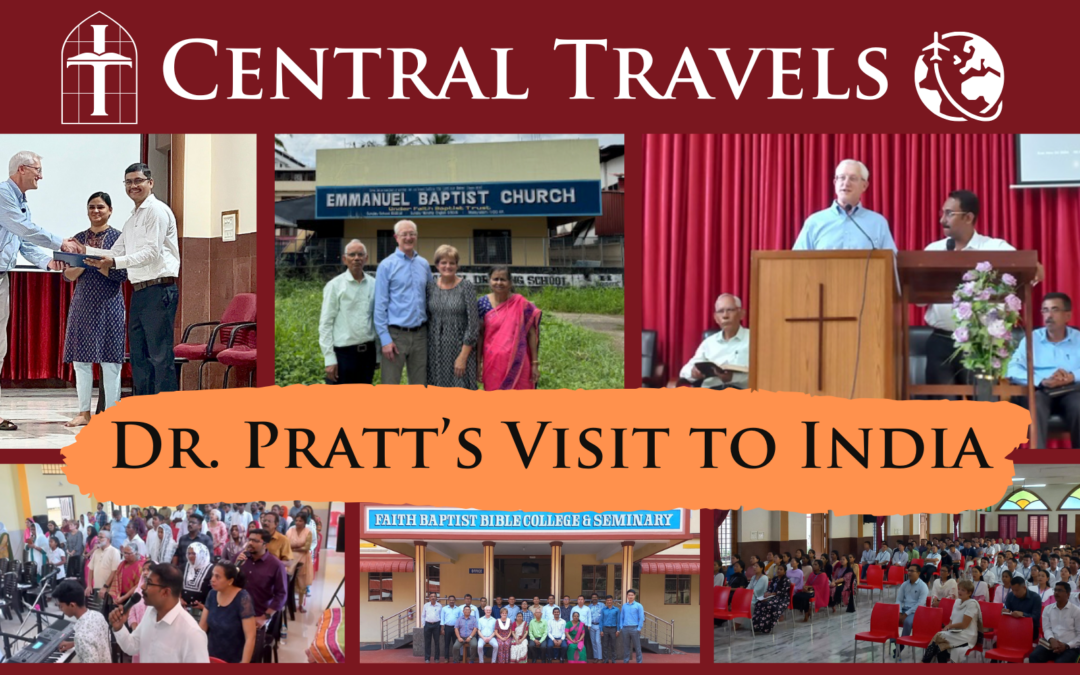

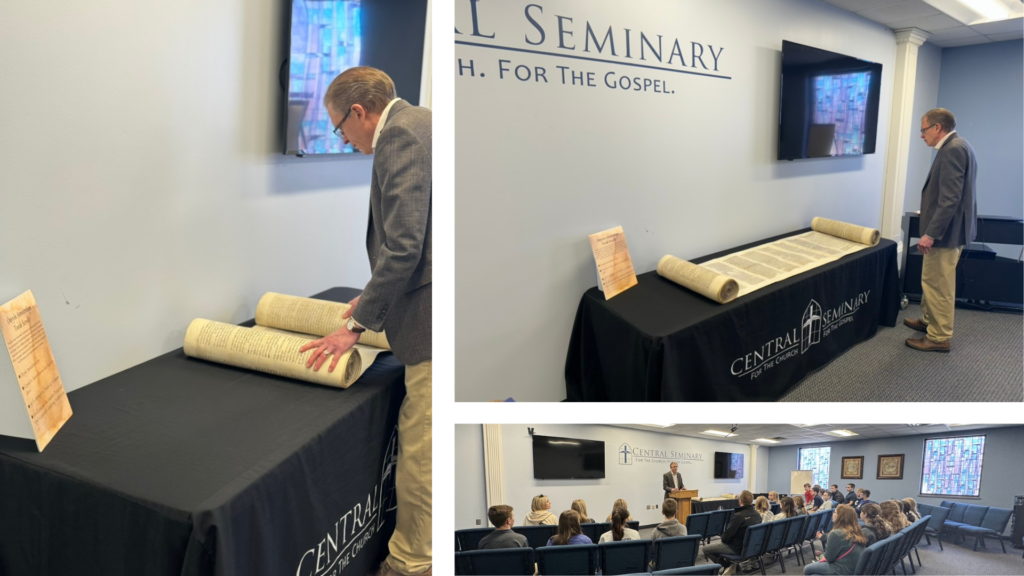

Dr. Pratt’s Visit to India

Dr. Jon Pratt, Vice President of Academic Affairs and New Testament Professor at Central Seminary, and his wife Elaine recently returned from their third trip to visit Faith Baptist Bible College and Seminary in Kerala, India.

A Growing Ministry

Dr. Sambhu De and his wife Molly minister in the southern region of India. Since Sambhu’s graduation from Central Seminary with a ThD degree, Fourth Baptist Church (Plymouth, MN) has served as the sending church for their ministry. They began by planting Emmanual Baptist Church out of their home. On the Pratts’ first visit to India in 2004, the church family was gathering in their home with plans for a church property. When the Pratts returned in 2016, they worshipped together with the church family at their completed property in Cochin city. Sam has also planted the Faith Baptist Church on the college campus in Kerala, about 40km north of Cochin. The pictures below are from the current church property in Cochin.

Emmanuel Baptist Church offers regular worship services in English and Malayalam, as well as a monthly combined bilingual service. Below is a picture of Dr. Pratt preaching through an interpreter and a picture of the congregation in Cochin.

Enriching Minds and Hearts

A significant part of Dr. Pratt’s visit was to deliver the opening messages for the college and seminary’s Spiritual Life Conference that begins each semester. Dr. Pratt spoke first on “Jesus is the Focus” with a message on the testimony of John the Baptist from John 3:22-26 and continued with sermons on assurance, perseverance, and sanctification.

Encouraging the Faculty

Additionally, Dr. Pratt met with the 19 faculty and staff members of FBBC&S for in-service and shared lessons from the life of Paul, emphasizing the importance of loving students through effective teaching. Dr. Pratt also had opportunities to speak in chapel and share devotionals to begin the days of classes.

Celebrating Achievements

During his visit, Dr. Pratt had the honor of personally delivering a Master of Arts in Theology diploma to Rajesh, a Central Seminary graduate who was unable to travel to the U.S. for his graduation ceremony in May. Rajesh is now pursuing his Master of Divinity through Central and is currently serving as Business Manager at FBBC&S while he continues his education. Dr. Pratt expressed Central Seminary’s gratitude for the support of generous donors who enable students like Rajesh to continue their education while serving in their local communities.

Further Missionary Connections

The Pratts’ travels extended beyond Kerala. Following their visit with Sam and Molly, they traveled north of India to Nepal to visit missionaries supported by their local church in Minnesota. God’s grace was evident throughout the trip, and the Pratts expressed their thankfulness for the many prayers and gifts that made this trip possible to see the impact of the gospel on the other side of the world.

Dr. Pratt on the Ministry in India

Reflecting on the trip to India, Dr. Pratt shared:

“It’s a great privilege to work with one of our alumni who has been faithfully serving for over 30 years. It’s a blessing to see the development of the campus and the ongoing ministry focused on training ministers and Christian workers for the gospel in India. The way is paved for that to continue into the future!”

“Just to witness God’s grace in using Sambhu over these many years and his faithful ministry in training young people for ministry is remarkable. It’s a privilege to be partners in the gospel with servants like Sam and Molly.” – Dr. Jon Pratt

Learn More:

- To learn more about the Faith Baptist Bible College & Seminary in Kerala, India, visit their website: https://fbbcindia.org/

- This fall, Dr. Sambhu De joined us on The Central Seminary Podcast to share about ministry in India. Listen here.

Faith Baptist Bible College & Seminary in Kerala, India

Faith Baptist Bible College was established on July 1, 1997 under the leadership of the present president, Dr. Sambhu Nath De. It was felt that there was a great need for such a Bible college in central Kerala.

Faith Baptist Bible College intends to produce God-fearing and Christ-honoring Christian leaders. They should be able to carry out the Great Commission of Christ boldly and defend the historic Christian faith effectively.

Bible classes are conducted in Assamese, English, Malayalam, Manipuri, Oriya, and Tamil languages.

Songs from the College & Seminary Choir

Central Seminary’s Global Initiative

Central Seminary’s relationship with Faith Baptist Bible College & Seminary is part of our Global Initiative to assist New Testament churches in equipping spiritual leaders for Christ-exalting biblical ministry worldwide. To learn how you can help encourage students worldwide, visit our Global Initiative page.

Central Seminary to Host ATS Accreditation Reaffirmation Visit in February 2025

Central Baptist Theological Seminary is hosting a comprehensive evaluation visit for reaffirmation of accreditation by the ATS Commission on Accrediting on February 17–20, 2025. The purpose of this visit is to verify that the school meets all applicable Commission Standards of Accreditation. Comments regarding how well the school meets those standards and/or generally demonstrates educational quality may be sent to accrediting@ats.edu at least two weeks before the visit. Comments may also or instead be sent in writing to Brett Williams, Provost, at bwilliams@centralseminary.edu. All comments will be shared with the onsite evaluation committee.

Almost Ready

My latest writing project is now in the final stages of proofreading and review. It should be in the hands of Central Seminary Press by next week, ready for typesetting and publication. The timeline for its release will, I hope, be measured in weeks rather than months.

This release will also include another title. It will be the second edition of my little book on Finding God’s Will. For the first edition we published only a couple thousand volumes, and they disappeared more quickly than we could have imagined. Because we were a bit unhappy with the cover design, we chose not to reprint it as it stood. Furthermore, since we were doing a redesign, I took advantage of the opportunity to update the book and to include a new chapter.

Finding God’s Will tries to chart a middle course between those who believe that God offers no individual direction for believers and those who follow their latest emotional burp as if it were God’s will for their life. The book maps out a procedure to discover how God is leading in one’s life, particularly when it comes to making big choices. I take the position that God does have an individual direction for the believer, and that He does lead believers, but that His leading never rises to the level of new revelation and that it is not a matter of subjectively listening for God’s voice. I insist that God leads His children through wisdom, and He does this providentially.

I begin by trying to dissuade readers from seeking God’s will through signs and “fleeces,” through listening for God’s voice (whether inner or outer), or through taking Bible verses out of context. Instead, I encourage believers to begin by submitting to all of God’s will that they find revealed in Scripture, by doing all to the glory of God, by fulfilling their duties, by bathing their decisions in prayer, by informing themselves about their choices, by seeking godly counsel, by considering their circumstances, by accounting for their inclinations, by developing a sense of vocation, and by understanding what role the peace of God plays. I also caution brothers and sisters about “buyer’s blues,” and I provide counsel about what to do when they know they’ve made a bad decision. In an appendix I summarize these steps in the form of a worksheet, and in a separate appendix I address the question of what a call to ministry looks like.

The goal in Finding God’s Will is to provide ordinary Christians with a manual that will walk them through the process of making decisions well. The book is easy to read and to understand. A pastor should be able to hand this book to any church member who is struggling with a decision. Working through the book will help that brother or sister. The book is also structured for use in Sunday School classes or home Bible studies, and it includes questions for reflection and discussion.

The other book—the new one—is entitled Communion and Disunion. It is a discussion of ecclesiastical fellowship and separation. These are not areas that every believer thinks about every day, but they are important areas that Christians and churches must address periodically.

Over the past thirty years, separation has been the topic that I have been asked to address most frequently. I have published journal articles and book chapters on the subject. I have written papers in formal and informal settings. I have delivered lecture series and preached sermons. What this book does is to gather several of those papers and addresses in one place.

Perhaps I should clarify one thing: when I say that the book is about ecclesiastical fellowship and separation, I do not mean that it is only about what churches do. What I mean is that our understanding of fellowship and separation must be grounded in a right understanding of the church if it is going to be biblical. Crucial to all decisions about Christian fellowship and separation is a correct vision of what the church is and who is included in it.

Communion and Disunion is also written for ordinary readers. No seminary training is necessary to follow the argument. It is also written with two readerships in view. On the one hand, I hope to help fundamentalists think through their doctrine of separation, which I believe is substantially correct but often poorly understood and sometimes badly applied. On the other hand, I hope to encourage non-fundamentalist evangelicals to adopt a more robust understanding of church unity and fellowship, an understanding that would result in a conscious appropriation of separatist categories. In short, if you are a separatist, I want to help you become more thoughtful. If you are thoughtful, I would like to help you become more of a separatist.

The likely result, of course, is that I shall encounter disagreement from both sides, and that is fine. I do not pretend to speak the final or authoritative word on this topic. The book is not a rigorous, scholarly treatment of fellowship and separation (such a treatment does not yet exist). Possibly, somebody may even convince me that I am wrong in important ways. But I think this is a conversation that needs to be advanced. Both fundamentalists and other evangelicals need to devote serious attention to the biblical and theological categories in which they talk about fellowship and separation. I will be pleased if the book stimulates conversation. I will be doubly pleased if it gets fundamentalists and other evangelicals to talk to each other about the subject.

Central Seminary Press is a function of Central Baptist Theological Seminary of Minneapolis. An in-house press of this sort always raises the possibility of less-than-rigorous standards when publishing materials from our own faculty. We try to mitigate that danger by seeking competent outside readers to review our materials before they go to press. Finding God’s Will has cleared that hurdle and is now awaiting typesetting. Communion and Disunion is in the hands of final reviewers and awaits their comments. The process should be complete by the end of Thanksgiving week, and both books will be going into typesetting soon.

So keep your ears open. You will probably hear more about these books before the end of the year.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

While Yet the Morn Is Breaking

Johannes Mühlmann (1573–1613); tr. Catherine Winkworth (1827–1878)

While yet the morn is breaking,

I thank my God once more,

Beneath whose care awakening,

I find the night is o’er;

I thank Him that He calls me

To life and health anew;

I know whate’er befalls me,

His care will still be true.

O gracious Lord, direct us,

Thy doctrine pure defend,

From heresies protect us,

And for Thy Word contend,

That we may praise Thee ever,

O God, with one accord,

Saying: The Lord our Savior

Be evermore adored!

O grant us peace and gladness,

Give us our daily bread,

Shield us from grief and sadness,

On us Thy blessings shed;

Grant that our whole behavior

In truth and righteousness

May praise Thee, Lord our Savior,

Whose holy name we bless.

And gently grant Thy blessing,

That we may do Thy will,

No more Thy ways transgressing,

Our proper task fulfill;

With Peter’s full affiance

Let down our nets again;

If Thou art our Reliance,

Our toil will not be vain.

Give to the Max 2024

Give to the Max 2024 is happening now through November 21. It is a major event sponsored by GiveMN, an independent agency that coordinates this special giving event for all kinds of Minnesota charitable organizations. The event aims for a “statewide outpouring of support for thousands of nonprofits and schools across Minnesota.” All gifts given during November count toward Give to the Max.

Central Seminary has been participating in Give to the Max for nearly two decades. This one event often provides a big part of our support every year. We rely on gifts from donors like you because students cannot pay the cost of seminary education. If pastors and missionaries are going to be trained, the bill must be paid by the people who will benefit from their ministries.

Consider Peter and his wife, Allie. They have two sons, Jonathan and Daniel. Peter grew up in a Christian home where God challenged him with the need for Christian laborers. Peter graduated from Appalachian Bible College and took an associate pastorate in Pennsylvania. Still actively engaged in pastoral ministry, he is also pursuing seminary training online at Central Seminary. During Peter’s studies, he and Allie continue to invest themselves in discipling new believers.

Another of our students, Mark, is married to Dannielle. Located in western New York, Mark was struggling to pastor part-time while simultaneously working an outside job and taking courses at Central Seminary. Then his employer eliminated his position without notice. The church stepped up and took Mark on full-time, and he is continuing his studies. They are grateful that Central Seminary’s online programs allow them to remain in New York. Mark is specifically grateful for encouragement from Central Seminary’s faculty, for reinforcement of his biblical convictions, and for the challenge to refine and expand his understanding of God’s Word.

Josh lives in California with his wife, Christy. He grew up in a mainline Protestant church that did not preach the gospel. He was saved when a friend invited him to a Wednesday night children’s program. Not long after he was saved, he started to feel a pull toward pastoral ministry. He attended Maranatha Baptist University, where he met and married Christy. Josh’s father initially opposed his desire to pastor but eventually changed his mind. Josh now serves part-time under a senior pastor in a local church and part-time at a Christian camp. Central Seminary’s distance-friendly educational model allows him to receive quality seminary education while he continues to serve in church ministry and to enjoy the mentoring of his senior pastor. He is excited to receive his degree and to transition into full-time pastoral ministry.

Taigen is a doctoral student at Central Seminary. He grew up near Seattle and was saved at the age of 15. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Bob Jones University, and he has pastored in Maryland and New Hampshire for over twenty years. He and his wife, Crystal, have twins who are seniors in college. New England is a difficult place to minister, but God is granting conversions and baptisms to Taigen’s ministry. He can work on his Doctor of Ministry at Central Seminary because Central Seminary’s accreditor authorized distance education for this program in the wake of COVID.

Théo Kabongo is one of three pastors at a church in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. He is husband to Agneau and father to Aletheia. Théo is passionate about spreading the gospel and seeing people’s lives being transformed by the power of God’s Word. The church hopes to start a Bible institute that will be supported by a church farm. In the meanwhile, Théo is one of many students in the Third World who are receiving their training from Central Seminary nearly free of charge.

Of course, Central Seminary still has students who move to Minneapolis. Joseph is one of our M.Div. students. Joseph grew up going to church, and from an early age he wanted to learn more about the Bible. He felt God’s call to ministry between his junior and senior years in college. Joseph plans to marry this coming May. In the meanwhile, he takes courses to prepare for pastoral ministry. He says that his education at Central Seminary is “super beneficial” as he anticipates full-time pastoral ministry.

Some of our students live in impoverished countries and live on subsistence wages. They can pay almost nothing for seminary training. Others of our students live in North America and have good jobs, but even they would go broke if they had to pay the full cost of their education. All of our students rely on donors like you. They trust the Lord to use people who will invest in their future ministries to cover the cost of their education.

Central Seminary is a great value for our students. It is also a great value for donors. As Doug McLachlan used to say, “We’re not fat cats.” We are careful with your money. We plan and budget deliberately to live within the Lord’s provision.

One donor is so convinced of the value of Central Seminary that he has put up $50,000 as a matching gift. If you give to Central Seminary for Give to the Max, your gift will automatically be doubled. Together, we can turn $50,000 into $100,000. This matching gift is a tremendous opportunity to help students who are preparing to serve the Lord in ministry for the rest of their lives.

Will you help us train future pastors and missionaries? We have made it convenient for you to donate in three ways. First, you can “Give to the Max” securely any time this month by following the link here. You can also give toward WCTS AM-1030 at wctsradio.com/give. Second, if you prefer to give by phone, you can reach Central Seminary on weekdays at (763) 417-8250. Third, you can mail a gift to Central Seminary at 900 Forestview Ln N, Plymouth, MN 55441. Thank you for helping us in God’s work of preparing pastors and missionaries.

What Shall We Offer Our Good Lord?

August Gottlieb Spangenberg (1704–1792); tr. John Wesley (1703–1791)

What shall we offer our good Lord,

Poor nothings! for His boundless grace!

Fain would we His great name record,

And worthily set forth His praise.

Great object of our growing love,

To whom our more than all we owe,

Open the fountain from above,

And let it our full souls o’erflow.

So shall our lives Thy power proclaim,

Thy grace for every sinner free;

Till all mankind shall learn Thy name,

Shall all stretch out their hands to Thee.

Open a door which earth and hell

May strive to shut, but strive in vain;

Let Thy Word richly in us dwell,

And let our gracious fruit remain.

O multiply the sower’s seed!

And fruit we every hour shall bear,

Throughout the world Thy Gospel spread,

Thy everlasting truth declare.

We all, in perfect love renewed,

Shall know the greatness of Thy power;

Stand in the temple of our God,

As pillars, and go out no more.

What a Trump Win Means

Conservative Christians throughout the United States are breathing a collective sigh of relief at the re-election of Donald Trump to the presidency. The reason is not that we are inveterate Trump supporters—far from it. Our expectations of his presidency are low. He is not the man to restore the moral fiber of our civilization. He will not return us to civility or bring an advance in reasoned discourse.

But then, we did not choose Trump primarily for what he is. We chose him for what he is not. In most elections of the past, we would not have voted for him. So why did we now?

One reason is that four years of incompetence, corruption, and radical ideology are enough. Biden, Harris, and their cronies gave us galloping inflation, military chaos, a porous border, rampant crime, divisive identity politics, and a weaponized legal system. Trump is not a paragon of order but compared to the past four years he looks positively OCD.

Another reason is that we have seen what the Left has tried to do to Trump. With the legacy media providing cover, they have reviled him at every opportunity. They have raided his home. They have engineered selective criminal prosecutions out of whole cloth. They have depicted him as such a threat to the country that multiple attempts have been made on his life. We watched as these things happened. We saw the unfairness of it all, and we could not escape the sense that anything the Left could do to Trump, they would eventually do to us.

Putting Tim Walz on the ballot only reinforced that perception. Walz is the guy who tried to promote gender confusion in the schools, even placing tampons in the boys’ restrooms. He told teachers to hide students’ gender confusion from their parents. He made it illegal for parents to refuse gender mutilation for their children. He weaponized Minnesota’s social services to pull kids out of homes where parents discouraged gender mutilation. He has made Minnesota into a state where normal parents have to live in fear. No wonder Harris and Walz received fewer votes from Minnesotans in 2024 than Harris and Biden got in 2020, while Trump received more.

Walz also enshrined abortion in Minnesota. With control of both houses of the legislature, he and his cronies passed laws to allow abortion up to the moment of birth. He has made Minnesota a destination for women who want abortions, and he has also turned Minnesota into a sanctuary for abortion seekers.

What Walz did in Minnesota, Harris and Walz were going to try to do at the national level. If they had been elected, they would also have tried to eliminate religious exemptions on these and similar issues. The Left is all about forcing people at gunpoint (every governmental ordinance and law is enforced at gunpoint). Harris and Walz wanted to force us to pretend. We would be made to pretend that a fetus is not a child, that two people of the same sex can marry each other, and that a man can be a woman and vice versa.

In some cases, Trump will also force us to pretend. He is the first president to be elected (in 2016) while publicly endorsing same-sex marriage. With Trump, however, there is at least some possibility that religious protections might remain in place. Under his administration, for example, Christian organizations might not be forced to pay for their employee’s abortions. Christian adoption agencies might not be put out of business for refusing to place children with same-sex couples. Artists of different sorts might not be prosecuted for refusing to celebrate events that are contrary to their consciences.

We also had other reasons for choosing Trump over Harris. Trump is less likely to interfere with our right to self-defense. He is more likely to uphold our property rights against radical ecotopians and predatory regulatory agencies. He is more likely to crack down on crime, and he is far more likely to defend the country from foreign invasion (whether armed or not). He has shown himself to be a friend of Israel. He has demonstrated his willingness to appoint judges who respect what the Constitution says, rather than what they wish it might say. Furthermore, as we learned from his first administration, Trump does not make promises that he does not intend to keep.

President Trump does not have the ability to fix our country. He is not the Messiah, and he will not lead us in either a civic or religious revival. Things may get worse rather than better under his presidency. But they should get worse at a slower rate than they would have under a Harris-Walz administration. President Trump cannot cure the disease, but he can temporarily ease some of the symptoms.

Curing the disease must begin with us. A Trump administration gives us a short reprieve, nothing more. We need to remember that the problems in our civilization cannot be addressed by mere legislation and enforcement. Law that is not felt in the heart does not hold power. Our job—not Trump’s—is to address the hearts of our friends and neighbors.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

When All Thy Mercies, O My God

Joseph Addison (1672–1719)

When all Thy mercies, O my God,

My rising soul surveys,

Transported with the view, I’m lost

In wonder, love, and praise.

Unnumber’d comforts on my soul

Thy tender care bestow’d,

Before my infant heart conceived

From whom those comforts flow’d.

When in the slippery paths of youth

With heedless steps I ran,

Thine arm, unseen, convey’d me safe,

And led me up to man.

Ten thousand thousand precious gifts

My daily thanks employ;

Nor is the least a cheerful heart,

That tastes those gifts with joy.

Through ev’ry period of my life

Thy goodness I’ll pursue;

And after death, in distant worlds,

The glorious theme renew.

Through all eternity, to Thee

A grateful song I’ll raise;

But oh, eternity’s too short

To utter all Thy praise.

Why That Name?

A respected colleague writes to ask why this electronic bulletin is named In the Nick of Time, or, to give its proper name, ΤΩ ΧΡΟΝΟU KAIΡΩ. He claims that he has often wondered about this question. Furthermore, he is sure that others would like to hear the answer.

Of course, a publication has to be named something. Whoever went to the library and asked to see an untitled book or periodical? If someone did publish such a document, it would be indistinguishable from other untitled books or periodicals. Readers would be forced to resort to some sort of ad hoc titling, such as “I’d like to see the untitled blue book,” or “Where can I find the untitled magazine from the National Forum?” Titles, whether formal or informal, are unavoidable.

The Nick (which is the—ahem—nickname we use) is one in a series of publications that I have produced in successive ministries. Long ago, when I was still in college, I was learning under a pastor in a small-town church that was located on that city’s Wall Street. The church needed a periodic informational mailing for upcoming events, and we called it the Wall Street Eternal. Later, as a pastor, I published a monthly paper printed on gold-colored paper. In a nod to Archer Weniger’s Blu Print, I called my publication the Gold Leaf.

While pursuing PhD studies I edited a bimonthly publication that was sent out by the Iowa Association of Regular Baptist Churches. Bob Humrickhouse was the association representative in those days, and we called the paper Ruminations. It included a hint of pungency that not everyone appreciated. I’m told that those who didn’t like it referred to the publication as Bauder’s Barf. The IARBC stopped printing it shortly after I made a comment about being an “unregistered” regular Baptist, then opining that it was not only possible but perfectly acceptable to be a regular Baptist without joining a fellowship like the General Association of Regular Baptist Churches. Incidentally, I stand by that thesis.

In the Nick of Time had its origins about twenty years ago. I was the relatively new president of Central Seminary, and I hoped to achieve a couple of goals through the new publication. First, I thought that we needed increased exposure among potential constituents, particularly students and pastors. Second, I wanted to experiment with a digital publication that could be distributed widely for minimal cost. Third, I wanted something more than a blog: I wanted a piece that would go directly to readers’ inboxes, and I wanted something that would be reviewed by the Central Seminary faculty before it went out. Fourth, I wanted a publication that would not be mine alone, but that other professors and friends of Central Seminary could write for.

Beneath all these goals, however, lay a deeper concern. I sensed that certain great ideas that had once been widely accepted within my circles were losing their hold on the imagination of the coming generation. Fundamentalism, with its emphasis on primary and secondary separation, was one of those ideas. Cessationism—the insistence that God is not granting miraculous gifts today—was another. Dispensationalism and its implied eschatology was another. Conservatism (both religious and political) rightly understood was still another. Liberal learning was another of the great ideas that I hoped to foster. Surrounding all these concerns was yet another great idea: the commitment to reasoned discourse.

By 2005, I suspected that all these ideas were poorly understood, even among the most Rightward evangelicals. The time was ripe for them to be re-articulated and defended. I wanted the new publication to do just that.

Because the hour was late and the ideas were slipping away, I felt a sense of urgency about the new publication. Barely enough time remained to make the case for these ideas, to reassure the wavering, and perhaps even to retrieve some who had already given up on the ideas. That was when my reading brought me across the happy expression, ΤΩ ΧΡΟΝΟU KAIΡΩ.

Literally, the translation would be “In the of time time.” The phrase, however, uses two different words for time. The word kairos views time as opportunity, while the word chronos views time as measurable. The first involves the quality of time, while the second measures its quantity. Thirty minutes is always thirty minutes: that is chronos. But thirty minutes spent getting a root canal does not feel the same as thirty minutes watching the Super Bowl. That is kairos. (In fairness I should note that my wife might view the root canal and the Super Bowl as nearly equivalent.)

So, what does ΤΩ ΧΡΟΝΟU KAIΡΩ mean? It means doing something at the most opportune (kairos) moment (chronos). The equivalent English idiom is in the nick of time, and it describes exactly what I wanted the new publication to be. ΤΩ ΧΡΟΝΟU KAIΡΩ is a last-moment plea to cling to or return to the great ideas.

If the situation seemed dire in 2005, it appears almost desperate now. The last vestiges of civil discourse are waning. Conservatism has been invaded by demagogues who despise genuinely conservative principles. Liberal learning has been canceled, to be displaced by indoctrination and bullying in the very centers that were supposed to maintain a commitment to education. Fundamentalism, cessationism, and dispensationalism have become nearly insignificant within the evangelical world. Allegiance to these and other great ideas continues to dwindle.

So, is it time to stop publishing In the Nick of Time? Or is it time to modify its stance and approach? Quite the contrary. In his essay on “Francis Herbert Bradley” in Selected Essays, T. S. Eliot writes that we sometimes defend lost causes, not because we can win, but because we are trying to keep something alive. If the great ideas are true—and I believe they are—then it is time to explain them, model them, and defend them better than ever before, so that they will remain available when a future generation again takes interest in them.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Life Is the Time to Serve the Lord

Isaac Watts (1674–1748)

Life is the Time to serve the Lord,

The Time t’insure the great Reward;

And while the Lamp holds out to burn,

The vilest Sinner may return.

Life is the Hour that God has giv’n

To ‘scape from Hell, and fly to Heav’n;

The Day of Grace, and Mortals may

Secure the Blessings of the Day.

The Living know that they must die,

But all the Dead forgotten lie;

Their Mem’ry and their Sense is gone,

Alike unknowing and unknown.

Their Hatred and their Love is lost,

Their Envy buried in the Dust;

They have no Share in all that’s done

Beneath the Circuit of the Sun.

Then what my Thoughts design to do,

My Hands, with all your Might pursue;

Since no Device, nor Work is found,

Nor Faith, nor Hope, beneath the Ground.

There are no Acts of Pardon pass’d

In the cold Grave, to which we haste;

But Darkness, Death, and long Despair,

Reign in eternal Silence there.

How to Vote 2024

The church’s place is not to address political questions. Rather, its work is to proclaim the whole counsel of God. Christian individuals, however, are responsible to act upon moral and spiritual concerns before they address merely temporal ones. Matters of principle should take precedence over matters of preference. Therefore, part of the church’s responsibility is to instruct the people of God in every moral principle that applies to their political decisions. In other words, while churches should not tell their members whom to vote for, they should teach them how to vote.

Political contests raise many issues that are not directly moral. Christians can certainly weigh these issues, but non-moral concerns should never take priority over moral ones. For example, candidates’ religious beliefs and affiliation do not usually determine how well they will govern. Christians might better vote for an unbeliever with just policies than to vote for a fellow saint whose policies are naïve or misguided.

Furthermore, governments have no moral responsibility to manage the economy, and when they try, the result is usually destructive. Governments have no moral duty to create jobs, to increase the wealth of their nations, or to supply the financial or medical needs of their citizens. Governments do not even have a moral duty to educate children.

Citizens may wish that their governments would do some of these things, but since they are not matters of conscience, they must not become the main issues that Christians consider when they are deciding which candidate to support. Rather, such issues must take a very distant second place to genuinely biblical and moral concerns. I here suggest ten biblical concerns that Christian people must weigh as they consider their voting choices.

Right to Life. From the time that government was established (probably Gen 9:6), its most important duty has been to protect the lives of the innocent. Civil authorities must use their power to defend those who are too weak to defend themselves. No one is more innocent than the unborn, who are clearly presented as human persons in Scripture (Psalm 51:5). Christians should reserve their votes for candidates who will work against the holocaust of abortion on demand.

Rule of Law. The clear teaching of the Bible is that law binds civil authorities. Any law that contradicts God’s law is, of course, unjust (Acts 5:29). More than that, rulers are bound by the law of the land that they rule (Ezra 5:13; 6:1-7; Acts 16:36-38). In the United States, the Constitution is the highest law of the land. But a Constitution that can mean whatever five justices want it to mean is exactly the same as no Constitution at all. Christians should support candidates who will only appoint or confirm judges who will abide by the meaning of the Constitution itself.

Restraint of Evil. A key function of government is to restrain evil (Rom 13:3-4). Externally, this means that the government must maintain a strong defense against national enemies and control the country’s borders against intrusion. Internally, it means governments must maintain the peace through effective policing. They must also enforce retributive justice against criminals through a just judiciary, remembering that “lawfare” is an attack upon the rule of law itself.

Respect for Property. The right to private property is protected by God (Exod 20:15). Few rights are more critical than this one. Great wealth rightfully gained is not a wrong but a blessing. Governments act immorally when they disintegrate the accumulation of wealth, whether through confiscation or through “progressive” taxes on income, estates, and capital. Christians should support candidates who refuse to make the government an expression of envy and an agent of economic redistribution.

Recovery of Moral Responsibility. God makes able-bodied people responsible for their own welfare (2 Thess 3:10). He has mandated that we should live by working. He expects mature people of every station to earn their living and to prepare for times when they cannot. For those who are overcome by circumstances beyond their control, God has ordained institutions such as family and church as agencies of support. Such institutions can provide help while holding individuals accountable. Casting government in the role of provider inevitably uncouples assistance from accountability and is deeply immoral. It is especially dangerous when the government’s activity supersedes the role of the family and negates its responsibility.

Recognition of Israel. God has not canceled His blessing for those who bless Israel, nor His curse for those who do not (Gen 12:3). While the modern state of Israel is not equivalent to the biblical Israel, it is related. Christian respect for and friendship to Jewish people ought to include support for the existence, autonomy, and liberty of Israel.

Responsible Use of Nature. God has given humans dominion over nature (Gen 1:26-28). Pristine preservation of nature is not God’s intention. We must recognize that the earth has been created for human use. Contemporary “environmentalism” often thwarts this divine design, and it must not be advanced by governmental regulation or policy.

Reputation for Integrity. When the wicked rule, the people mourn (Prov 29:2). The personal character of political candidates affects their ability to serve in office. A candidate whose word cannot be trusted is one who cannot govern well. Integrity is particularly important when it comes to a candidate’s sworn word. A candidate who violates the marriage oath is the kind of person who will violate an oath of office. Yet a candidate who has erred in the past may show a change of heart by consistent promise-keeping in the present.

Rightness of Personal Defense. God forbids murder (Exod 20:13), and no one must submit to being murdered. Furthermore, God assigns a duty to deliver those who are about to be murdered (Prov 24:11–12). The right to personal defense is given by God. Governments have no authority to deprive citizens either of this right or of the necessary means of exercising it. Christians should support candidates who will not limit access to the means of personal defense.

Reality of Marriage, Sex, and Gender. There are only two natural sexes, and only two natural genders that are inextricably linked to them (Gen 1:27). Natural marriage always involves a union of one partner from each sex (Gen 2:24). Legal requirements to recognize other arrangements are not only contradictory and wicked, but tyrannical. Christians must support candidates who will not undermine these realities.

The last three election cycles have failed to give Christians any presidential candidate who meets all these criteria, and candidates for other offices are usually not much better. Even so, some candidates are worse than others. Given that government is ordained by God for good (Rom 13:4), Christians faced with imperfect choices should choose the greater good. They should make their choice, at minimum, by the criteria that I have listed above.

They must also resist being driven by material concerns. Their primary interests are not economic. Their duty is to seek first the kingdom of God. Biblical principles should take priority over personal preferences at the polls, just as they should in every area of life.

![]()

This essay is by Kevin T. Bauder, Research Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Not every one of the professors, students, or alumni of Central Seminary necessarily agrees with every opinion that it expresses.

Our Nation Seemed to Ruin Doomed

Philip Doddridge (1702–1751)

Our nation seemed to ruin doomed,

Just like a burning brand;

Till snatched from fierce surrounding flames

By God’s indulgent hand.

“Once more,” He says, “I will suppress

The wrath that sin would wake,

Once more My patience shall attend,

And call this nation back.”

But who this clemency reveres?