Theology Central

Theology Central exists as a place of conversation and information for faculty and friends of Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Posts include seminary news, information, and opinion pieces about ministry, theology, and scholarship.Thinking about a PhD?

Trevin Wax is a recent PhD graduate. Here he offers his counsel concerning things to think about “Before You Go for a PhD.” It’s good advice.

Congratulations to Jeff Straub

Wipf and Stock has agreed to publish Jeff Straub’s doctoral dissertation, “The Making of a Battle Royal: The Rise of Liberalism in Northern Baptist Life, 1870-1920.” Dr. Straub’s dissertation, written for Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, is the most complete explanation to date of how liberal theologians captured control of the Northern Baptist Convention. The published work should appear during the late summer of 2017.

Don We Now our Ge Apparel…

Christmas came early for me this year. After several years of desire, my parents bought me prints of two of my favorite paintings: “Quid veritas est?” and ” Last Supper,” both painted by my Russian realist, Nikolai Ge (1831-1894). Ge is well-known for his friendship with Tolstoy and dissenting views of the Russian Orthodox Church. His religious works garnered first fame, then revile, even producing an governmental charge of blasphemy. He attacked the Christo-Iconography of the Russian Church and painted the God/Man as a man; ugly, abused, forlorn, and often in darkness. For Ge, Jesus’s humanity reflected his primary purpose; to be the propitiation of the world.

Carolyn Pirtle, of Notre Dame, brilliantly explained Ge’s “Last Support here.

Jefferson Gatrall wrote a good piece on Tolstoy and Ge’s vision of Christ here.

Sadly, the Eutychianism of 18th century Russian Iconism is alive and well today. Mainly in terrible art, poor worship, and proper Evangelicalism. Images of the Messiah have become so ubiquitous that he has, ironically, become unrecognizable. Remember the child born of the young Theotokos. Remember the homeless vagabond, remember the suffering Saviour, true God and true Man.

Spot On

Noah Livingston addresses an urgent problem in “Saving the Funeral from an Untimely Death.” He’s right–very right–in most of what he says.

When the funeral becomes a cordoned family affair, it degenerates into a matter of personal preference. it becomes a vehicle for self-expression, one last gasp at leaving one’s mark on the world. When it ceases to be congregational worship, it ceases to be an event where God’s people are formed. Too often, pastors lead the way.

The only point at which I would (mildly) disagree with Livingston is where he suggests having someone “tell a story or two” about the deceased. Not the I object to stories about the deceased if they are rightly done. The problem is that they are rightly done so seldom. Except in rare and special instances, the minister should be the only one to speak at a funeral.

Collin Hansen’s Top Stories

Here are Collin Hansen’s “Top 10 Theology Stories of 2016.”

Tozer on What We Need

I do not believe we need more religion; we need a better kind of religion. My great burden these days and for many years has not been for an extension of the kind of religion we have now. It has to be an improvement of the kind we have and then an extension of that. The one great loss we have suffered in the evangelical world, the one great overwhelming, calamitous loss that has been the cause of all these other losses is one: a loss of God. The most high God, maker of heaven and earth— that awesome God before whom our fathers fell— that God has left us, and in His place has come that God of the half-saved, who want to get chummy with God and treat Him like the chairman of some committee.

Tozer, A.W. Delighting in God (Kindle Locations 578-583). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

What Is a Conservative?

No one has improved on the description originally provided by Russell Kirk, who summarized the conservative perspective in six core principles. The list appears in plenty of places: here is one.

Kevin De Young’s Top Ten Books List

I like to know what people are reading, and I like to know what they liked. Here’s Kevin De Young’s “Top Ten Books of 2016.”

Sylvester Stalone to Become Arts Czar?

Is this fake news?

The Daily Mail is reporting that Donald Trump has picked movie star Sylvester Stallone for a government post. The most likely position is head of the National Endowment for the Arts. Predictably, the arts community is hyperventilating.

On the one hand, I can sympathize with their distress. The thought of Rocky and Rambo deciding who gets funding to make art leaves me dumbfounded. But then, the NEA’s choices already leave me dumbfounded. This is the outfit that funded Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorp (old news, now, dating back to the 80s and 90s). Most recently, the NEA has been accused of directing artists to produce works that promoted President Obama’s domestic agenda.

So taken on balance, maybe Rambo would be an improvement. At an rate, it should deflate some of the self-importance of those who consider themselves artistic gatekeepers.

Comfort, Comfort Ye My People

Paraphrased from Isaiah 40:1-5

By Johann Olearius

Tr. by Catherine Winkworth

Comfort, comfort, ye my people,

Speak ye peace, thus saith our God;

Comfort those who sit in darkness,

Bowed beneath their sorrows’ load.

Speak ye to Jerusalem

Of the peace that waits for them;

Tell her that her sins I cover

And her warfare now is over.

Yea, her sins our God will pardon,

Blotting out each dark misdeed;

All that well deserved His anger

He no more will see or heed.

She hath suffered many a day,

Now her griefs have passed away;

God will change her pining sadness

Into ever-springing gladness.

Hark, the Herald’s voice is crying

In the desert far and near,

Bidding all men to repentance

Since the Kingdom now is here.

Oh, that warning cry obey!

Now prepare for God a way;

Let the valleys rise to meet Him

And the hills bow down to greet Him.

Make ye straight what long was crooked,

Make the rougher places plain;

Let your hearts be true and humble,

As befits His holy reign.

For the glory of the Lord

Now o’er earth is shed abroad,

And all flesh shall see the token

That His Word is never broken.

Questions:

This paraphrase is usually sung as a Psalm during Advent, typically to lively music.What sensibility does it primarily express? Why is this appropriate during the Advent season?

Still Don’t Get It?

I suppose I don’t blame you. If you’re from anywhere south of the 4oth parallel, you panic when you look at this kind of snow. You wonder how people can live in weather like that. You think they must freeze all winter long.

Well, I took this picture about a mile into this afternoon’s walk. As you can tell from the angle of the snow, there was a good bit of wind. The temperatures weren’t polar, but they were cold. And I was enjoying myself.

What’s the secret? Just this: you dress for where you’re at. If you go out rambling in the Arizona desert, you wear a hat. If you go out walking in Minnesota snow, you wear a good coat. A quality pair of long johns and a lined pair of jeans will help.

My winter coat is the old N3B military parka. It’s kept me warm in temps down to about 35 below, which is about as cold as it gets in Minnesota. But it’s also comfortable in weather like I was in when I took this picture. If I pull up the hood over my stocking cap, I’m more than warm, even with the wind blowing.

About a mile later, I was chased by a pack of dogs. There were four of them, and I could see them coming through the snow, barking as they ran. They were wiener dogs, and it was a sight. The snow was higher than their legs, so they had to jump to make progress. They looked like four walleyes leaping and splashing through the lake as they hove toward me.

Their owner had just let them out of doors and they wanted to play. You’ve never really lived until you’ve been mobbed by a pack of dachshunds in the snow. It was a riot.

Winter is nothing to fear. It is fun–just a different kind of fun than lying around the beach. The nice thing about Minnesota is that you can do both. You have the beach for part of the year and the winter for part of the year. Not to mention the brilliance of fall and the sudden burst of spring. In Minnesota they talk about what they call the “theater of seasons,” and it’s quite a show.

When you look at that picture, don’t shiver. In Minnesota, it’s no big deal. In fact, it’s even a cause to celebrate. In the northern part of the state, parents don’t think twice about sending their kids out to play when the temp is -10 or even colder. It’s a way of life that brings its own compensations.

Bard Replaced by Lesbian Activist

Students at Penn have taken down a portrait of William Shakespeare and replaced it with a portrait of Audre Lorde. According to the Poetry Foundation, Lorde characterizes herself as a “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” who has devoted her life “and her creative talent to confronting and addressing the injustices of racism, sexism, and homophobia.” Her work was denounced as obscene by Senator Jesse Helm. Read the report at The Daily Pennsylvanian.

This Week’s Nick

Kevin Bauder writes about “Hearing the Message.”

Aunt Hazel’s Pancake Breakfast

Every fall semester during finals week the Central Seminary faculty cooks breakfast for the students. The event is named for a former dean’s Aunt Hazel, who contributed an original recipe for banana pancakes. Buttermilk pancakes are also available, as are eggs and sausages. This long-standing seminary tradition expresses the gratitude of the faculty for the hard work that our students do to prepare themselves for the Lord’s work.

Russell Moore on the Religious Right

First Things reprints the text of Moore’s 2016 Erasmus Lecture, “Can the Religious Right Be Saved?” Here is part of his answer, a part that says he really has no answer. Whenever an evangelical starts talking about “cultural renewal,” we are in trouble. If you doubt it, just look at the culture of American evangelicalism. That’s what they want to renew the culture TO.

The religious right can be saved, but not by tinkering around the edges. Religious conservatives will need a robust religion and a sense of what is, in fact, to be conserved. This will mean abandoning an idea of a “moral majority” or a “silent majority” within the nation, even when we find ourselves winning an election or a court case. We will need to build collaborative majorities, often issue by issue. It will mean institutions that have the vision, and the financial resources, to play a long game of cultural renewal, rather than allowing themselves to be driven by the populist passions of the moment. More than that, it will mean a religious conservatism that sees the Church as more important than the state, the conscience as more important than the culture, and one that knows the difference between the temporal and the eternal. We will make mistakes. We will need course corrections. We must remind ourselves that we are not inquisitors but missionaries, that we can be Americans best when we are not Americans first.

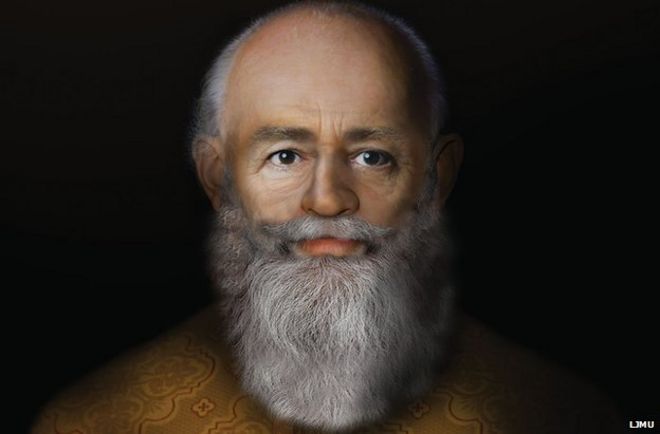

What Saint Nicholas Really Looked Like

Using advanced facial reconstruction technology, British researchers have produced what they claim is the most accurate depiction ever of the face of Saint Nicholas of Myra (Santa Claus). Or so the BBC reports.

Conservatism and Ideology

Many people–including many conservatives–think of conservatism as an ideology. They would be surprised to learn that thoughtful conservatives reject ideology of every sort. They insist that their position is not an ideology, but an attitude. Read more from Gerhart Niemeyer in “Russell Kirk and Ideology.”

Conservatism cannot be shrunk to the principle that everything in human life should be reduced to the economics of the marketplace, an idea which in its poverty is first cousin to Marx’s historical materialism. Nor can we do better by linking conservatism to John Stuart Mill’s individualistic society, which may be compared to an ocean of atomized islands having no communication with one another. Nor can we fall back on Locke’s human rights, the condition on which each isolated person enters human community by the gate of quid pro quo. These and other similar worldviews have nothing to say to the reality of living human beings with body and soul, mind and spirit. They have oozed from a consciousness deliberately separated from living reality, which has sweated abstract realities out of itself. This is the ideological mind building thought systems around utopian fantasies with which to manipulate human beings into false hopes.

The Artistic Theologian

The Artistic Theologian is a peer-reviewed journal of ministry and worship arts. It is published by Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas. Back issues are available for download in PDF and Logos formats. The Artistic Theologian is edited by Scott Aniol and will be of special interest to conservative Christians.

How to Tie a Full Windsor

A gentleman needs to be able to tie his own necktie. In fact, a gentleman should master at least three necktie knots–which he uses will depend upon the tie, the outfit he’s wearing it with, and the occasion he’s wearing it for. The most basic knot is the full Windsor. Here’s a tutorial from The Art of Manliness.

Tozer’s Favorite Hymn Writers

Ah, the roster of the sweet singers. There is Isaac Watts, the little man that nobody would marry because he was so homely, but he wrote hymns, and what hymns he did write. Meditating on an Isaac Watts hymn will take you further into the presence of God than any song sung today.

Also, there was Nicolaus Zinzendorf, an accountant and wealthy businessman, who was marvelously converted in the Moravian church. He became the leader in the church, and under his ministry came a great revival. Some of his hymns were “Jesus, the Lord, Our Righteousness”; “O Come, Thou Stricken Lamb of God”; “Jesus, Thy Blood and Righteousness”; and “Jesus, Still Lead On.” Ah, and what hymns.

Then there were men like Charles Wesley, Isaac Newton, William Cowper (“ There Is a Fountain Filled with Blood”), James Montgomery, Bernard of Cluny, and Bernard of Clairvaux. Then there was Paul Gerhardt, Tersteegen, Kelly, Anderson, and Toplady. The list goes on and on of the sweet singers of God.

Tozer, A.W. Delighting in God (Kindle Locations 526-533). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.