Few deny that the modern American religious landscape has been shaped by revivalism. From Whitefield to Finney, Wesley to Sunday, revivalism has played a vital role in the formation of evangelicalism. In fact, one cannot understand North American evangelicalism without first understanding revivalism. Revivalism, like all religious phenomena, cannot be rightly examined outside its events and personalities. Indeed, one such event and one such man personally contextualizes 20th century revivalism more than most. The man: Billy Graham. The place: Los Angeles. This post will examine the Billy Graham Los Angeles Crusade of 1949 as a definitive event leading to a rebirth of revivalism in the mid 20th century. It will accomplish this by comparing certain distinctives of revivalism to the events that occurred in and the characteristics of the crusade.

The Crusade

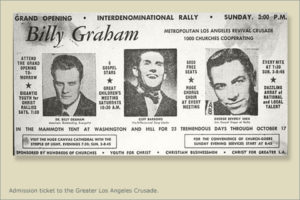

A brief overview of the events of the crusade is necessary to begin this comparison. In early 1949, the executive committee of the “Christ for Greater Los Angeles” committee invited Graham to host revival meetings in Los Angeles.[1] This committee hosted annual revival meetings, and always invited a well-known fundamentalist preacher to gather a respectable crowd. The meetings were to be nightly, beginning on September 25 and continuing for three weeks.[2] Although Graham desired a large-scale event, he was faced with apathy and even pessimism. Many churches and pastors did not enthusiastically support the meetings. In one instance, Graham and an associate had visited a local Los Angeles church for the midweek service and, while the pastor cordially asked for prayer concerning the meetings, he closed by saying the possibility for a great revival in that area was, to the learned student, “a lot of nonsense.”[3]

This type of attitude did not deter the zealous Graham however, who sent another associate, Grady Wilson, to Los Angeles to organize a massive prayer effort. As a result, things began to take shape. William Martin states, “For the first time, a Billy Graham campaign began to assume what would eventually become its mature form. Nine months before the meetings began, he engaged veteran revivalists Edwin Orr and Armin Gesswein to conduct preparatory meetings throughout the Los Angeles area.”[4] Graham wanted to begin a grassroots organization that would set these meetings apart from any other. Graham pulled out all the stops by insisting that the Christ for Greater Los Angeles committee spend $25,000 for posters, billboards, and radio announcements. Graham recalls these media spots as having a three-fold purpose: “First, they were to try and broaden church support to include as many churches and denominations as possible. Second, they were to raise their budget from $7,000 to $25,000 in order to invest more in advertising and promotion. Third, they were to erect a much larger tent than they had planned.”[5] As a culmination of his efforts, he met with the Hollywood Christian Group to ask the actors and actresses to use their names and testimonies to influence the campaign.[6]

On the eve of the meetings, Graham was plagued with theological doubts and questions, the most important being the inerrancy of Scripture. After being counseled by friends and spending a night of reflection and introspection in the dry mountains outside Los Angeles, Graham came down refreshed and inspired. Like a modern-day Moses, Graham attacked the pulpit with energy of a zealous prophet. After a rousing musical performance and a plea for financial offerings, Graham opened the meetings with a sermon entitled “We Need Revival.” The thrust of his message was an attack upon the materialism, immorality, and paganism of contemporary America along with a plea for a return to “old time religion.”[7] His message was filled with fervor and his oration was that of an honest backwoods preacher, pleading with his fellow humans. In the end, it was apparent that the audience was spiritually moved, some even visibly shaken. Even so, after two weeks of nightly meetings, not much was happening. Initial press releases only received six inches of space on the back page of the next day’s paper.

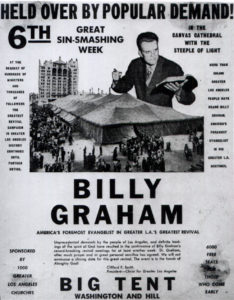

Thus far, the meetings were not the success that Graham had hoped for. During the final week however, two events changed Graham’s outlook and the nation’s perception. First, media tycoon, William Randolph Hearst instructed his journalistic minions to “puff Graham,” commanding an army of editors to make Graham front-page news.[8] Instantly, hundreds of reporters and photographers swarmed the crusade, not only reporting nearly every word, but also describing in details the mood and response of the listeners. Overnight, Graham’s revival meetings were transformed into a media frenzy. The second event involved an unlikely ally from among Hollywood’s elite. Stuart Hamblen, a popular radio talk host and known gambler, announced on his radio show that Graham’s ministry had helped him become a Christian and was going to change his life around.[9] The combination of Hearst’s media empire and Hamblen’s popularity made Graham an instant celebrity, propelling him to the popular spotlight with stories in Time, Life, and the Associated Press.[10] After meeting with his team, Graham decided to extend the meetings from three to eight weeks. At the end of the crusade, all expectations and attendance records had been crushed. 350,000 people had attended the 70 meetings and a total of 2,703 made first time decisions for Christ.[11] The numbers, however could not include the thousands of families that were changed and the total spiritual fruition of the work. Graham’s crusade had been a resounding success.

Evaluation

To examine the Los Angeles Crusade in light of normative revivalism, one must first set up parameters to define revivalism. Russell Richey, in his article, “Revivalism: In Search of a Definition,” clearly defined and described revivalism in its American context. [12] Richey proposes that the study of revivalism is not necessarily a portrayal or screen, but a constellation of ingredients. These ingredients form a cohesive unity of characteristics, providing a backdrop on which to examine certain religious phenomena, such as the Los Angeles Crusade.

Richey’s first characteristic of revivalism is that it is founded upon Pietism. He states, “The association of revivalism with Pietism is so close that one can hardly appropriately ask whether revivalism has existed or can exist apart from Pietism. Certainly, we can argue that a pietist-like ethos seems vital.”[13] Pietism’s emphasis upon spiritual expression and experience acts as a direct adhesive to the personal aspect of revivalism. Communal revivalism cannot occur divorced from personal devotion, responsibility before God, and the sensitivity to the Holy Spirit.[14] The Los Angeles Crusade was characterized by a “pietist-like ethos.” For example, in his first sermon, Graham outlined the steps needed for revival to occur in Los Angeles. He said, “First, realization of a need and desire for revival. The second condition for revival is repentance. Do you know what repentance is? Repentance is confession of sin, . . . sorrow for sin, . . . [and] renouncing sin. And then the third is to pray.”[15] It is certainly no stretch to clearly see the emphasis on a deeply personally and spiritual endeavor.

The second characteristic of revivalism is a theology and practice that is conducive to aggressive proselytism.[16] McDow and Reid are quoted as saying, “Every revival in history has produced significant numbers of conversions.”[17] The Los Angeles Crusade was the most significant mass evangelistic event since Billy Sunday’s revivals. The numbers were staggering. Thousands of people eagerly waited on the corner of Washington Blvd. and Hill St. each afternoon to hear the preacher in the “Canvas Cathedral.” Graham even wrote to his friend Luverne Gustavson, “If you could have seen the great tent packed yesterday afternoon with 6,100 people and several hundred turned away, and even scores of people walking down the aisles from every direction accepting Christ as personal Savior . . . .”[18] As stated before, attendance estimates surpassed 350,000 people, and with over 2,000 salvation decisions, the Los Angeles Crusade certainly qualifies as a major revival.

This crowd phenomena produces more than mere numbers, it produces a visible sign that engraves itself into the psyche of a generation. Richey states, “Revivalism proper, . . . does not refer to change that happens piecemeal over time and that might be discernable only after the fact. It is a visible event, a visible happening, and a species of crowd behavior. Revivalism happens. It happens to crowds.”[19] The Los Angeles Crusade was not an unusual causal event in a chain reaction that produced slow growth; it was an explosive event that captured the area by storm. One could hardly ride a Los Angeles cab in late October of 1949 or sit in a beauty parlor without overhearing a rousing conversation about Graham. Harold J. Ockenga later said of Graham concerning a New England revival, “For two hundred years there has been no such movement in New England. George Whitefield was the last man who stirred New England in such a way.”[20] Indeed, all of America opened newspapers and tuned to frequencies to hear news of Graham’s revival. This aggressive proselytism and immediate popular phenomena that characterized revivalism prior to the mid 20th century was now suddenly evident in Los Angeles.

The next characteristic of revivalism to examine as it pertains to Graham’s crusade is its tendency to assume societal and cultural declension.[21] Russell states, “It would perhaps be more accurate to say that revivalism assumes a worldview in which declension is premised – nature is pitted against grace.”[22] He demonstrates that there are two aspects to this characteristic. First, revivalism holds the major premise of a sort of theological entropy; the world will wax worse and worse. The minor premise is assumed that God has judged, is judging, and will judge societal evil on a massive scale. The conclusion; because the world is waxing worse, and God will certainly judge societal evil, then the recipients of the sermon – partakers in the evilness of society – are to repent lest terrible judgment fall upon them.[23] This type of societal damnation preaching had existed well before Graham and is truly indicative of revivalism. Charles Finney is said to have once preached in a small town where he was unknown. During the singing, he noticed that the audience was filled with “wild-looking” men, many in their shirtsleeves. Finney immediately stood up and quoted from Genesis saying, “Up, get out of this place, for the Lord will destroy this city.”[24] He subsequently referred to that particular town as “Sodom.”[25] Leonard Ravenhill, in his passionate plea for revival said, “How right Edwards was! What obligations has God to a people like us whose aggregate sin as a nation in one day is more than the sin of Sodom and her sister city, Gomorrah, in one year?[26]

In a homiletical sense, Graham’s Los Angeles Crusade was classic Finney. In his opening sermon, “We need revival,” Graham began by reading Isaiah 1:1-20. He then immediately posed a choice to the audience, “Remember, the verse we just read, ‘Except the Lord of hosts had left unto us a very small remnant, we should have been as Sodom….’”[27] He wasted no time in tearing into the audience by using examples from his recent visit to Europe to tell of the devastation and absolute wreckage that humanity can cause. He stated that the only reason why America escaped such wreckage is because of godly people. However, America would not escape for long! He delved into the topics of moral corruption, crime, sexual promiscuity, gambling, teen-age delinquency, and alcoholism, giving statistics with every subject. He climaxed by disclosing the ever-popular war between Western culture and Communism.

Communism is not only an economic interpretation of life – Communism is a religion that is inspired, directed and motivated by the Devil himself…. Now for the first time in the history of the world we have the weapon with which to destroy ourselves – the atomic bomb. I am persuaded that time is desperately short! Three months ago, in the House of Parliament, a British statesman told me that the British government feels we have only five to ten years and our civilization will be ended.[28]

Certainly, Graham used pre-tested and evidently successful revivalist techniques in his homilies. The presence of direct societal declension and impending judgment were crucial to Graham’s plea.

The next characteristic of revivalism is communication network. Richey defines this as “a means by which the Spirit’s working becomes known, a way by which a specific episode or series of conversions are claimed by the larger community.”[29] There are three aspects to this characteristic: pre-revival communication networking, continuous communication during a revival, and post-revival effect. The pre-revival communication is absolutely essential to the success of revivalism. Originally, pre-revival planning was made up of mainly prayer. A.T. Pierson said, “There has never been a spiritual awakening in any country or locality that did not begin with prayer.”[30] In 1859, D. L. Moody established a group of prayer warriors known as the “Illinois Band” to pray before and during any board or revival meetings.[31] Preparation also included some form of logistical plan. Focusing on laymen and committee involvement, as well as advertisements were prevalent.[32] Graham took this ideology to an extreme. In late summer of 1949, the Christ for Greater Los Angeles Committee shifted the crusade planning into high gear. They were able to get some 250 Protestant churches involved – almost a quarter of the Protestant churches in Los Angeles.[33] As stated previously, Graham insisted that the advertising budget be raised to an unprecedented $25,000. Celebrity endorsement, the full support from a Youth for Christ-style campaign, and even public endorsement from the mayor all helped to spread the message. Prayer teams from churches and para-church organizations were released en masse. This pre-revival communication and advertisement network dwarfed all previous.

Though the turning point did not come until during the crusade – Stuart Hamblen’s radio address and media mogul Randolph Hearst’s simple command to perpetuate Graham propelled the crusade to new heights. These two key events changed the outcome of the crusade and would leave an indelible mark on pre-revival networks for years to come.

Even after the crusade ended, the effects of the pre-revival preparations and the events during the revival itself reverberated throughout the country. This reverberation was carried along on the backs of modern media. The full effects of Hearst’s blessing were now being felt. Newspapers throughout the country ran full-length articles on the “Old Time Religion That Sweeps Los Angeles.”[34] Graham concluded his thoughts on the effect of the revival by saying

When we [Graham and his wife] got to Minneapolis, the press was again there to interview us… Until then it had not fully registered with me how far-reaching the impact of the Los Angeles campaign had been. I would learn over the next few weeks that the phenomenon of that Los Angeles tent Campaign at Washington and Hill Streets would forever change the face of my ministry and my life. Overnight we had gone from being a little evangelistic team, … to what appeared to many to be the hope for national and international revival.[35]

Another key aspect in recognizing true revivalism is its distinct liturgy. While individual liturgical forms may vary in relation to their respective geographical locations and cultures, there is still always a definite ritualistic form that each revival will take.[36] For example, the well-known revivalist Charles Finney introduced the “altar call” during the Cane Ridge Revival.[37] Though people would often rush forward after a service as the result of revival, Finney made this emotional phenomenon normative by issuing an “explicit invitation to come down the aisle as a response to the gospel, a move that was quite effective in bringing about the desired results.”[38] Another example would be Finney’s “anxious seat.” He arranged several pews in the front of church to “assist” people who wanted to get right with God.[39] Emotional appeals and psychological manipulations created an experiential liturgy, which continued to defined revivalism.[40]

Graham’s preaching and invitation style resembled this liturgical form. Dazzling performances, massive banners, emotional pleas, and spellbinding soloists were all part of Graham’s repeated repertoire. [41] Instead of “dry” orthodox church surroundings, Graham’s crusade was held in a massive “Canvas Cathedral” complete with sawdust floor, thousands of seats, and plenty of aisle room for the invitation.[42] Graham not only typified revival liturgy but also set an undeniable precedent. Almost every crusade that followed was patterned after the style and practice of the Los Angeles Crusade.[43]

The final aspect of revivalism is charisma. Revivals tend to center around a charismatic leader or preacher. Richey states, “Specifically, they [revivals] depend upon charismatic leadership. It is the leader, the revivalist, around whom the drama of a revival unfolds. So critical have been the revivalists to the phenomenon that we tend to conflate the two, revivalist and revival.”[44] Often the success or failure of the revival rests squarely upon the shoulders and talents of said individual. This charisma is manifested in several different ways. First, physical language plays a vital role in charismatic leadership. Powerful sentiments and stirring oration are indispensable to the revivalist. C. H. Spurgeon once said of Whitefield’s sermons – after only reading them “In these sermons one perceives the coals of Jupiter and hot thunderbolts, which mark him out to be a true Boanerges (son of thunder).”[45] Another type of language, not merely body language, but also excitement, severity, and action is just as necessary. The famed evangelist Billy Sunday was said to be a “physical sermon.” Describing Sunday, William Ellis said “The intensity of his physical exertions – gestures is hardly an adequate word – certainly enhances the effect of the preacher’s earnestness. Some of the platform activities of Sunday make spectators gasp. He races to and fro across the platform. One hand smites the other. His foot stamps the floor as if to destroy it.”[46]

Though Graham was not an acrobat or “son of thunder” per se, he embodied the physical and oratory excitement necessary for leading a revivalistic event. Stanley High, another early biographer, described Graham’s oral and physical delivery by saying “The way he preached was pretty much in the tradition of the ‘Hot Gospeller.’ His voice was strident. He was inclined to rant. The same sound effects in politics would, in most places, be called demagoguery.”[47] McLoughlin adds, “The drama of Graham’s delivery is heightened by the way he acts out his words. As he retells the old Biblical stories of heroes, villains, and saints, he imitates their voices, assumes their postures, struts, gesticulates, crouches, and sways to play each part.”[48] Graham described his own feelings when he preached the Los Angeles Crusade saying, “I felt as though I had a rapier in my hand and, through the power of the Bible, was slashing deeply into men’s consciences, leading them to surrender to God.”[49] During the Los Angeles Crusade, Graham’s preaching seemed to come alive with fervor. His charisma engulfed his whole body and his physical communication struck every soul. His preaching certainly followed in the steps of past revivalists.

Another aspect to charismatic leadership is popularity. Every era in revivalism can be readily identified with either one individual or a small group of individuals. While this is broadly true for all Christian eras, it is especially apropos for revivalism. Popularity, power of message, and organizational abilities can all contribute to revivalist leadership. Benjamin Franklin once described Whitefield as a leader “who could at any time and anywhere, collect in the open air, an audience of many thousands, with out offering a single heretical novelty.”[50] It is no stretch to think that if Franklin were impressed with the abilities of Whitefield during that era of revivalism, he would be obliged to recognize Graham’s during the Los Angeles Crusade. It was said that, “it would seem to be God’s purpose to choose a man who will sum up in himself the yearnings of his time – a man divinely gifted and empowered.”[51] Graham clearly fit the bill. Not only did Graham precipitate the resurrection of revivalism, he also became its new identity. Popular Graham biographer, James Kilgore even claimed that Graham should “be counted in the company of Charles G. Finney, George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, D. L. Moody, and Billy Sunday.”[52] Revivalism had been reborn and rebranded.

Conclusion

The Los Angeles Crusade of 1949 was more than a mere revival; it was the rebirth of revivalism in the mid 20th century. The characteristics of revivalism were all clearly present in Graham. The crusade clearly created a pietistic-like ethos and Graham’s messages were founded in an evangelism that was conducive to aggressive proselytism. Thousands and thousands were emotionally charged and spiritually changed. His message proclaimed cultural digression and impending societal doom. Graham planned the crusade with an aggressive communication network that exploded with growth during the crusade and continued with ramifications well after. The style and practice of the crusade directly emulated the liturgical past of revivalism. Graham began to embody important leadership abilities during this crusade that would soon propel him to international fame and define him as the undisputed guru of modern revivalism.

[1]William G. McLoughlin, Billy Graham, Revivalist in a Secular Age (New York: The Ronald Press Company, 1960), 45.

[2]Ibid.

[3]Good News in Bad Times (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1953), 155.

[4]William Martin, A Prophet with Honor (New York: William Morrow and Company Inc., 1991), 113.

[5]Billy Graham, Just as I am (San Francisco: Zondervan, 1997), 144.

[6] Martin, A Prophet with Honor, 113.

[7] McLoughlin, Billy Graham, Revivalist in a Secular Age, 47.

[8]Ibid.

[9]Fred Hoffman, Revival Times in America (Boston: W.A. Wilde Company, 1956), 173.

[10]Joel Carpenter, Revive Us Again (New York: Oxford Press, 1997), 226.

[11]Orr, Good News In Bad Times, 161.

[12]Wall Street Journal 28 (1993): 166. In this article, Richey explores ten distinctives of revivalism and describes their relationship to historical events. All ten need not be explored because several are subsets of one another.

[13]Ibid., 167.

[14]D. Martin Lloyd-Jones describes these in his chapter on the characteristics of revival. He directly ties personal pietism as foundational to corporate revival. D. Martin Lloyd-Jones, Revival (Westchester, Ill.: Crossway Books, 1987), 105-117.

[15]Billy Graham, Revival in Our Time (Wheaton: Van Kampen Press, 1950), 59.

[16] Richey, “Revivalism: In Search of a Definition,” 285.

[17]Malcolm McDow and Alvin Reid, Firefall (Nashville: Broadman & Holman 1997), 21.

[18]John Pollock, Crusades: 20 Years with Billy Graham (Minneapolis: World Wide Publications, 1969), 59.

[19] Richey, “Revivalism: In Search of a Definition,” 169.

[20] McDow and Reid, Firefall, 304. This is pertinent because the Los Angeles Crusade of 1949 was the model for nearly every following revival until 1960.

[21] Richey, “Revivalism: In Search of a Definition,” 168.

[22] Ibid.

[23]Graham once said, “Just one wrong move by some of our diplomats could plunge us all into eternity by intercontinental missiles and hydrogen bombs. Come and give your life to Christ while there is still time.” Charlotte Observer (Charlotte), 16 October 1958.

[24]John Shearer, Old Time Revivals (Philadelphia: The Million Testaments Campaign, 1932), 57.

[25]Ibid.

[26]Leonard Ravenhill, Sodom had no Bible (Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers, 1971), 27.

[27]Graham, Revival in Our Time, 53.

[28]Ibid.

[29] Richey, “Revivalism: In Search of a Definition,” 171.

[30] McDow and Reid, Firefall, 117.

[31]Ibid., 119.

[32]W. A. Tyson, The Revival (Nashville: Cokesbury Press, 1925), 60-62.

[33]Carpenter, Revive Us Again, 222.

[34]Billy Graham, Just as I am, 144. This was a November headline for an Indiana newspaper. After such phenomena, Graham said, “Reporters were comparing me with Billy Sunday, church leaders were quoted as saying that the Campaign was ‘the greatest religious revival in the history of Southern California,” 151.

[35]Ibid., 158.

[36]Richey, “Revivalism: In Search of a Definition,” 170. “Revivals are revivals and are recognizable as revivals because they have definite ritual form.”

[37]Douglas Porter and Elmer Towns, The Ten Greatest Revivals Ever (Ann Arbor: Servant Publications, 2000), 102.

[38]Ibid.

[39]Ibid.

[40]See Raymond Edman, Finney Lives On (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1951). The chapter “The Pattern of Revival: The Pew and the Pulpit.” Edman describes Finney’s reasoning for his preaching and service forms.

[41]See Robert J. Wells, “Music and the Revival,” ed. How to Have a Revival (Wheaton: Sword of the Lord Publishers, 1946).

[42]William Martin, A Prophet with Honor, 112.

[43]See Pollock, Crusades: 20 Years with Billy Graham.

[44] Richey, “Revivalism: In Search of a Definition,” 171.

[45]Mack Caldwell, George Whitefield, Preacher to Millions (Anderson, Ind.: The Warner Press, 1929), 112.

[46]William Ellis, “Billy” Sunday, The Man and His Message (n.p., L. T. Myers, 1914), 138. One chapter in this book is entitled “Acrobatic Preacher” which includes a fanciful caricature chart of Sunday’s postures and expressions.

[47]Stanley High, Billy Graham (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1956), 86.

[48] McLoughlin, Billy Graham, Revivalist in a Secular Age, 125.

[49]Billy Graham, “Biblical Authority in Evangelism,” Christianity Today 1 (1956): 6.

[50] Caldwell, George Whitefield, Preacher to Millions, 112.

[51]James Kilgore, Billy Graham the Preacher (New York: Exposition Press, 1968), 25. Kilgore is quoting Charles Cook in reference to Graham.

[52]Ibid., 16.